On the Road in 1980, Part 3

Madonna, Mexico City (1980) by Graciela Uterbide

I stayed two days in Guadalajara. On the train ride to the city, I met Rafael, warm and talkative, coming from Los Mochis up the coast to find work. We ended up looking for a place together, Rafael leading us into a neighborhood I might’ve steered clear of on my own, between the train station and Plaza de los Mariachis, where we found a cheap room with two beds at the Hotel Cinco de Mayo. My first night, waiting for an order of tacos from a street vendor, I was approached by a girl, maybe fourteen or fifteen, ripped sweatshirt and blue jeans, dark hungry eyes, tongue slowly licking her lips, indicating that her boombox needed batteries. She spoke in a rush; I didn’t understand half of what she said but knew what she meant. Facing a force capable of pulling me out of myself and into a state of thrilling danger, I replied, “No, gracias.” I was not averse to risk, but I could see how badly it might all end, both for me and her.

I did get my Mexico travel visa replaced in Guadalajara, but the American consulate could provide no help with my “lost” passport. The second night, Rafael went on a bender, staggering into our room two or three times, a bottle of mescal in hand, inviting me to join him. He never made it back that night. I awoke the next morning to the warbling of the hotel’s lovebirds. When I left, I was stuck with the whole bill.

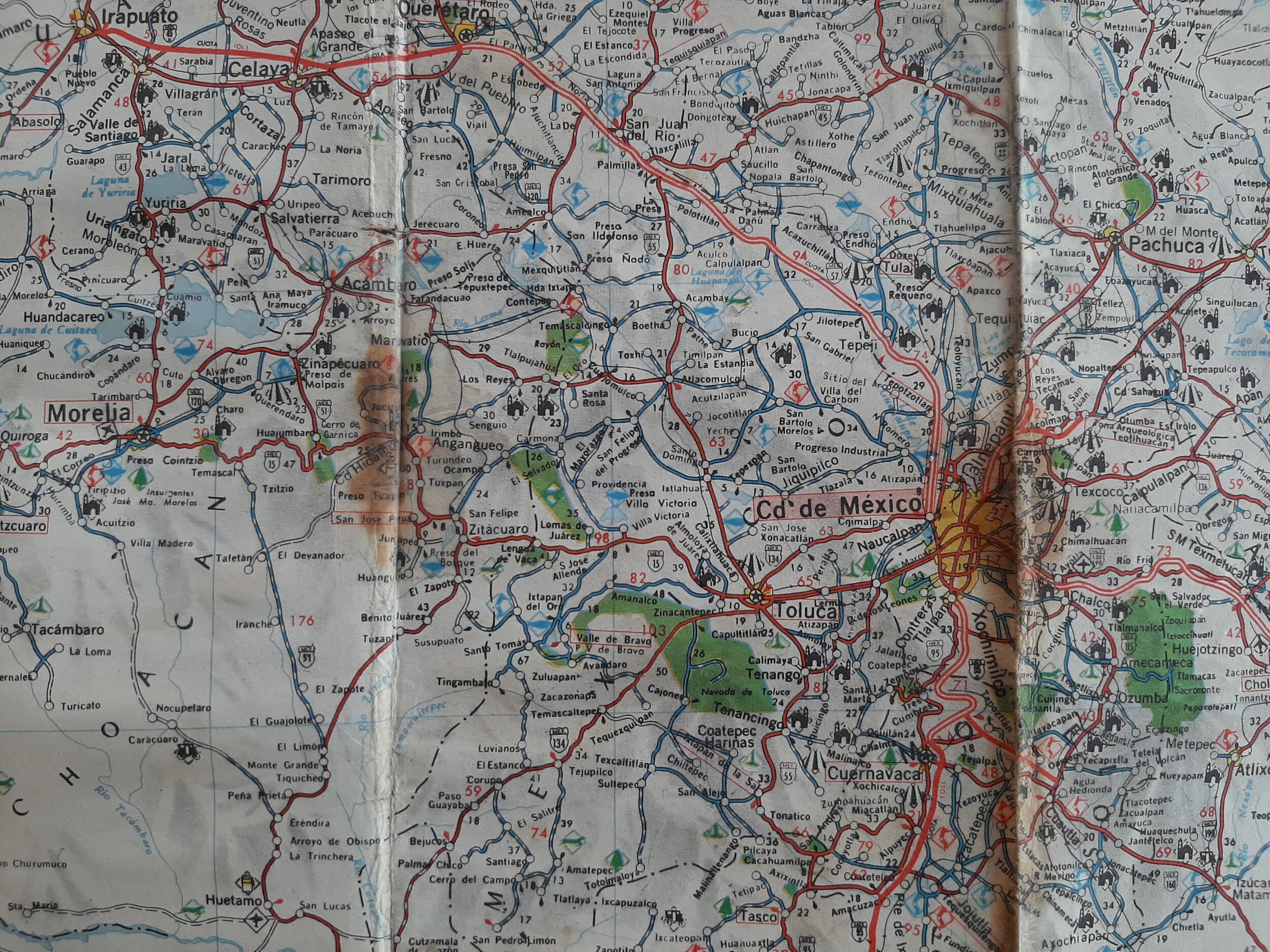

It felt good to get back to hitchhiking – swinging my rucksack up on my back, sticking out my thumb, waiting for something to happen. I let my rides dictate my meandering easterly route across the Mexican Altiplano, through Jalisco and into Guanajuato – Tepatitlán de Morelos, San Juan de los Lagos, Lagos de Moreno. My last ride of the day took me to the eastern edge of León. I hiked across fields of corn and green onions and into the foothills of a mountain range, camping among saguaro and nopales. settling in for one of those “Long Nights” of tranquilidad.

As I was reviewing my dreams in the first streaks of dawn, a campesino passed by and began a monologue I understood little of. A half hour later, I chatted with three men and a gaggle of kids. Then one Rosalio Rocha stopped to invite me to his home for a breakfast of un café and sopa de frijoles con chorizo. I was welcomed into Rosalio’s adobe home, his wife cooking over an open fire on the dirt floor, two shy niños hiding behind her skirts. It was a beautiful moment – I was amazed and humbled by their heartfelt generosity.

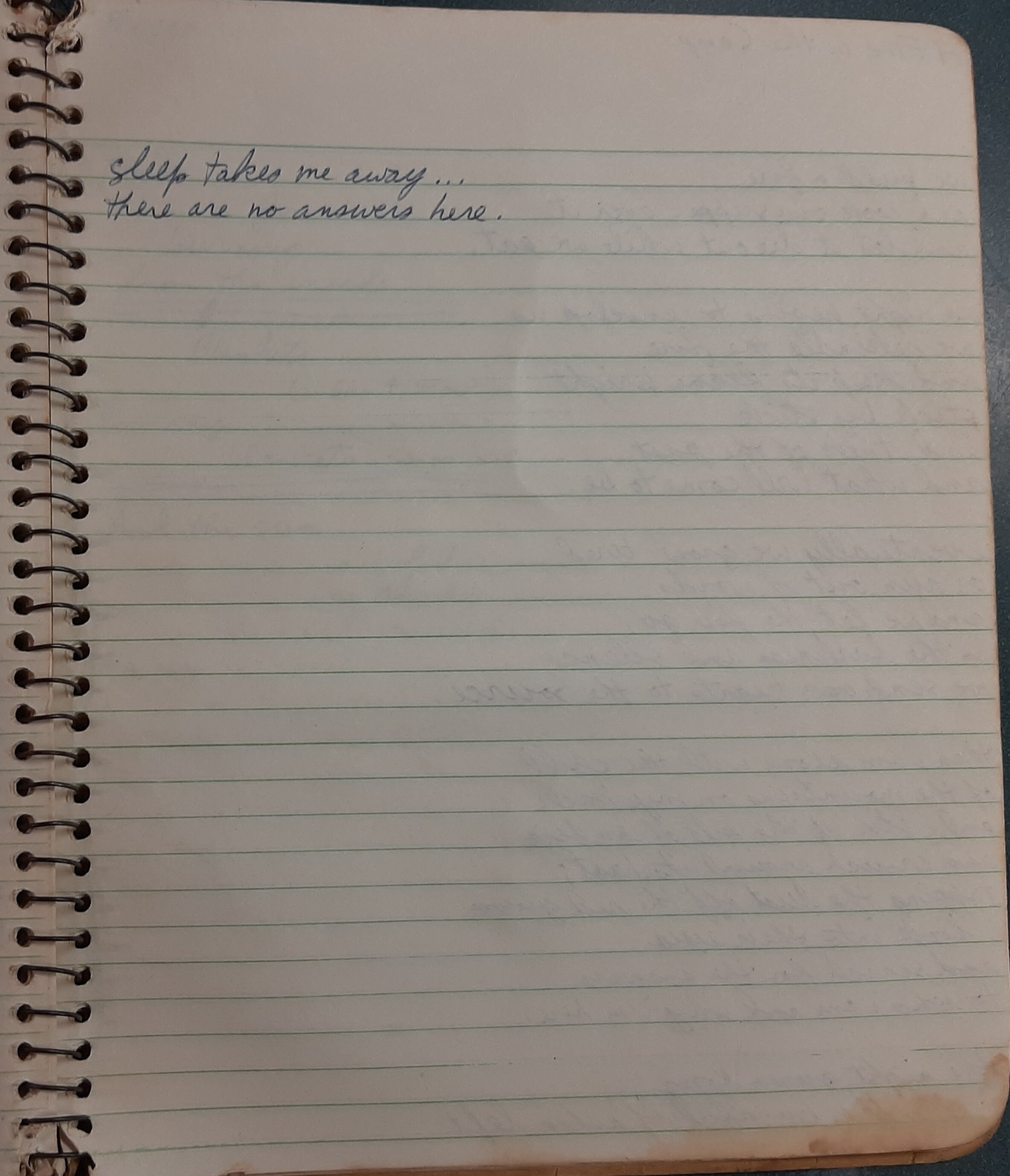

A young mining engineer named Ángel gave me a ride from León to Guanajuato. He and his younger brother Ramon invited me to stay in a spare room in their apartment, and I did so for two days. I hung out quite a bit with Ramon, an amiable and mellow law student. Ángel was willing to share more than his apartment; after he brought home a woman from the disco and they had engaged in some rather boisterous sex, he knocked on my door, offering her to me. I respectfully declined, explaining I was tired from wandering the city all day. I had other reasons for refusing a gift that wasn’t his to give. But I truly had been wandering that colonial city, enchanted. My journal contains the following appreciation: [1]

There is a city I know. A subterranean street runs its length, passing beneath the public buildings that withstand like monuments. The road and its walls, its arches and ceiling, are constructed of large blocks of stone the people had discovered in the mountains above the city.

The city nestles in canyons under the shadow of these mountains, arms of houses stretching to the left and right of the main thoroughfare. Alleys so narrow that but one person can pass at a time descend the hillsides by means of steps, emptying the various pockets of the city.

The homes are washed in colors of aquamarine and lavender, tangerine and canary. Their shapes exemplify the strictness of the right angle, and considerable use is made of the flat roof space. During the day, this is a delightful place to be – lines of white clothing wave in the sunlight, wives whistle their unique language to each other across the rooftops. Families take their midday meals here, feasting on the panorama, acknowledging the passersby on the highway that hugs the hillsides like a shelf, encircling the city.

This peculiar form of speech I have encountered – how to translate its code of sibilants? An afternoon stroll is punctuated by the casual hissing of greetings. And the sounds of the morning market – an aviary awakened! This idiom adequately serves the city, though it preserves neither the vocabulary of philosophy nor any sense of a future tense.

In the evenings, the people gather to fill the gardens of the many plazas, listening to the final daysongs of the mockingbirds that nest in trees trimmed to form geometric designs. There is no public lighting – the entire populace dresses in white (even the beggars and shoeshine boys) and the city is graced with a perpetual moon that strikes the meeting places luminous.

Above the city is an old palace inhabited by a collection of mummies buried a century ago and maintained by minerals in the soil. From behind glass cases, they reflect gaping-mouth wonder, as if amazed by death, or by the lives they left behind.

When night does fall, it is complete. I walk in utter darkness, the silence broken only by the occasional exclamations of lovers. The cobblestones of each street have become as familiar as the knuckles of my hands, yet I have found no true road leaving this city.

I did leave Guanajuato, though, hitching to San Miguel de Allende, camping outside the city along the sandy banks of a stream. I hiked into San Miguel to check out the Instituto Allende, a well-known visual arts college popular with American and Canadian students. Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, and other Beats spent time there in the 1950s, but the scene no longer seemed interesting. I walked out of the city to a dry plateau, camping behind the roofless ruins of a small chapel. Desert twigs for a cookfire, empty open spaces, coyotes yelping at the roar of a plane. Whether in a city around people or hanging out with myself, I learned something either way.

The next morning I hitched a ride to Querétaro, where I stopped for a lunch of café con leche and pan dulce, then leaped the 200 kilometers to Ciudad de México in two quick rides. A woman in the train station in Guadalajara had given me the address of a student hostel, so I decided to check it out. It was near the Bosque de Chapultepec, in the Zona Rosa,[2] only 70 pesos per day for a dormitory bed and a breakfast. But I needed a student card, which cost me an additional 150 pesos, including the ID photo. The cost was not considerable in terms of US dollars ($6.50), but my goal to travel for at least two more months was dependent on my frugality.

View of the Pyamid of the Moon from atop the Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacán

I spent four days in Mexico City. One was devoted to visiting the Mesoamerian archaeological site at Teotihuacán, a 50-kilometer bus ride northeast of the city. I climbed the Pyramid of the Sun and surveyed the broad valley stretching far to all sides, imagining what this must’ve looked like at its height some fifteen centuries ago, when according to population estimates, it was the sixth-largest city in the world.

After spending an entire morning cutting through swaths of red tape at the US Embassy, I was finally able to get a new passport, thanks to my voter registration card, of all things. And once I had that new passport, I visited the Guatemalan Embassy and obtained a travel visa for that country.

That glazed look on my face - weariness from battling American consulate bureaucracy.

The multilingual and multinational array of young travelers at the hostel offered its own entertainment. My last night there, a group of us went out on the town, traipsing from bar to club to private party, dancing and drinking cuba libres. We headed back to the hostel long after all public transportation had shut down. Laughing and goofing, our motley and besotted crew skipped down the middle of the normally busy Avenida Paseo de la Reforma, giving each other a boost so we could sneak in through an unlocked window at four a.m.

Footnotes:

[1] The piece was influenced by Italo Calvino’s Imaginary Cities, published in 1972 and translated into English in 1974.

[2] That trendy boho neighborhood was nearing the end of its heyday.

On the Road in 1980, Part 2

Mujer ángel, Desierto de Sonora (Angel Woman, Sonoran Desert), 1979, Graciela Uturbide

By mid-February I was crossing the border into Mexico. My circuitous route from Iowa City via San Francisco to the border took four weeks as I eased into the flow of travel and recalibrated the balance between getting somewhere (making miles) and being somewhere. After spending a wild week in Tucson with my old friend Tony Hoagland,[1] I hitched down to Nogales and easily crossed into Mexico. I checked out the buses and trains going south, taking a bus simply because it departed sooner, a six-hour, 400-kilometer ride due south to Guaymas, the first good-sized city on the Gulf of California.

When I left San Francisco over two weeks earlier, I hitched just 100 miles down the Pacific Coast Highway to Santa Cruz. I located my friend Theresa from Iowa City, who had just moved there and was living a couple miles outside of town up a dead-end canyon road. Like some nymph of the redwoods, Theresa and her sweetness kept me lingering in that mellow beach town for almost a week, but I also yearned for the regimen and introspection of the road. “Society, … I hope you're not lonely without me.”[2] On my way to Tucson, I wrote in my journal, “Beginning to look forward rather than back. Paying attention to my actions and transactions. Are the things I do and say equivalent to my feelings, my emotions, my convictions?”

I passed the time on the bus to Guaymas in conversation with my seatmate, using the opportunity to brush up on my conversational Spanish skills. He was a friendly guy, buying me tamales and guayabas from the vendors who crowded the bus in whatever dusty Sonaran village it stopped to take on or discharge passengers, passing their wares up through the windows. When I got to Guaymas, everyone I met was directing me to nearby San Carlos, mistakenly assuming I wanted to be where all the gringos were. Nevertheless, I took their advice, catching a local bus that took me there in a half-hour. Faced with the growing darkness and weary from traveling all day, I quickly found a quiet spot on the beach and set up camp. The next morning I discovered I was surrounded by beauty, situated on a lovely little bay backed by scrub desert and beyond that the craggy mountains and canyons of Cajón del Diablo.[3]

I also discovered my passport was missing. After frantically ransacking my backpack, I went back to Guaymas and checked at my two stops there – the taquería and the bus station – but it hadn’t turned up. The more plausible explanation for my passport’s disappearance implicated my amiable seatmate, who was likely making plans to put it to good use before it expired in five months. I gave myself a stern talking to about not being on my game and not keeping an eye on my essential possessions. On the other hand, I felt good about having perhaps facilitated his immigration plans.

While at the station, I met a young simpatico Norwegian guy, Per, who was preparing to catch a train south, but after I’d mentioned the beach I was camping on, he decided to join me. Meanwhile, I contemplated my options for replacing my passport: retracing my steps to the States, going directly to the American consulate in Mexico City, or traveling at my own pace and accepting the risk of getting stopped by the federales sin papeles.

We stayed just one more night on the beach in San Carlos. When the weather turned cloudy and windy and cool the next morning, we agreed to pack up and head south. We scoped out our options: trains or buses down the coast toward Mazatlán or ferries across the gulf to Baja California. While at the bus station, we met Kathy and Diane, down from San Francisco for a little getaway vacation. After chatting a bit, we bought a six-pack of Pacifico and found a quiet spot down by the harbor where we could drink and continue our conversation. By the time we finished another round of beers at their hotel room, they had persuaded themselves to go with us to Mazatlán. The purposes of our journeys were quite different, but neither Per nor I had any qualms about letting them join us for a while. They were fun to hang out with, and Kathy did speak fairly good Spanish.

By midnight we were catching the train from nearby Empalme, and as the sun rose the next morning we were approaching Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa, two-thirds of the way to Mazatlán, a lively Pacific seaport of over 200,000 people. It hosts one of the best Carnaval celebrations in Mexico, a week-long street party that would be just kicking into gear the day of our arrival. On the train, we met Bill from Montana, a rangy, knowledgeable guy with an easy-going drawl, who joined our little entourage and recommended we all head for Isla de la Piedra.

After disembarking in Mazatlán, we quickly sussed out the scene and found our way to the docks, where we caught a ferry launch across the mouth of the harbor to Isla de la Piedra, actually a long peninsula that sheltered the harbor. The ferry took us to a small fishing village, from where we hiked about a kilometer to a beautiful beach sheltered by a grove of coconut palms stretching southeast for miles. The only buildings were a few open-air thatched-roof restaurants, one run by a Mexicana named Linda, who catered especially to the gringo hippies camped there. The current assemblage included Americans, Germans, Swiss, Italians, Brazilians, Swedes.

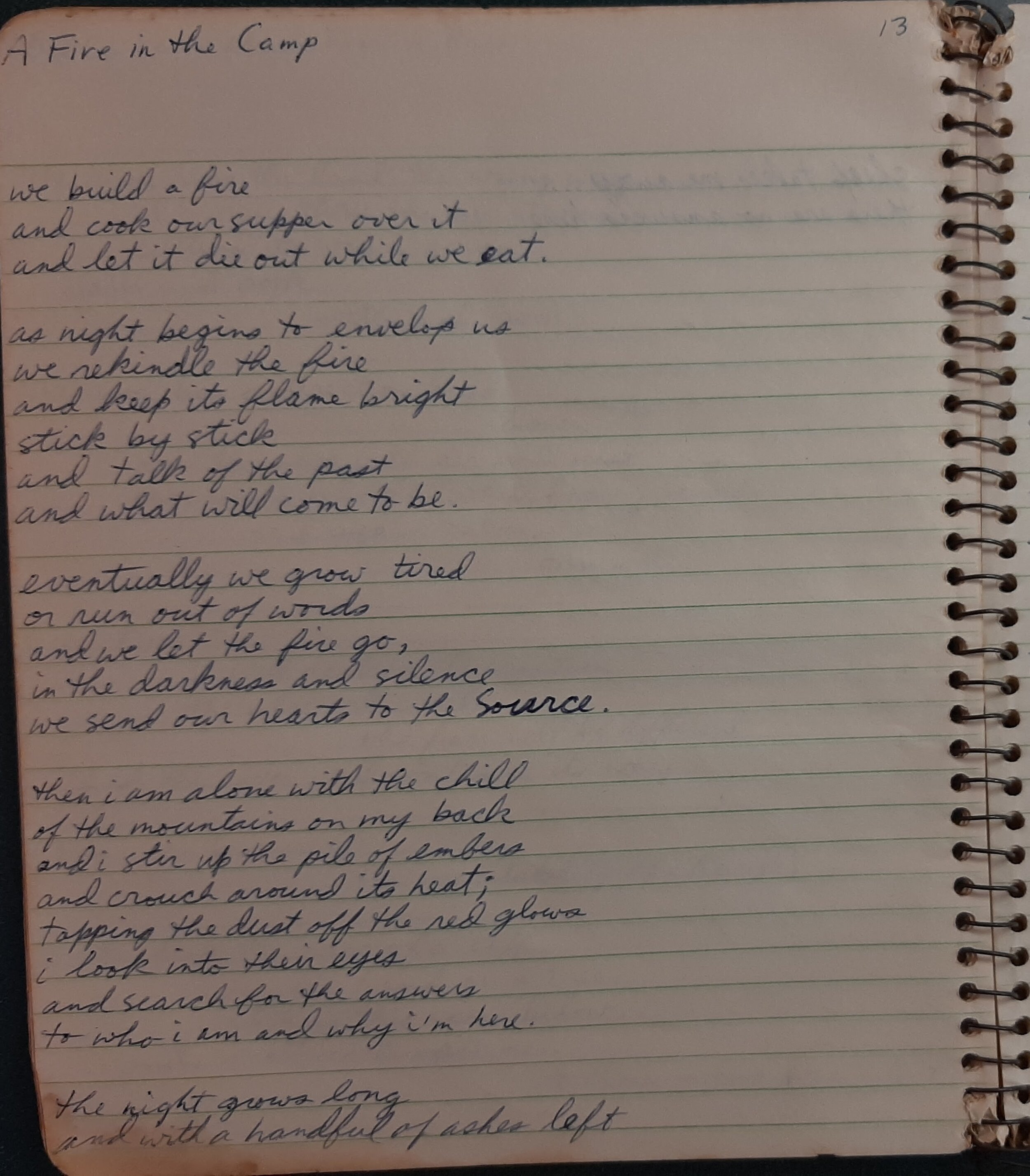

I was delighted to join this international gathering. We made our campsite near others scattered along the back edge of the beach. Bill was particularly handy as we rigged up a shelter of coconut palm fronds and tarps to protect us from the midday sun and the steady northwest winds that picked up with the new moon. I romped in the sea, body-surfed, gathered freshly fallen coconuts for drinking, and played bocce with German Siegfried and Swiss Catherine, using empty coconut shells. At night we’d gather around a bonfire on the beach, smoke pot, drink rum and Kahlua, drum on improvised percussion instruments, and sing and howl at the moon. It seemed much farther from Mazatlán’s Centro than a half hour by foot and ferry.

On Saturday night, a group of us went into the city to experience Carnaval. Mazatlán’s version is much tamer and more family-oriented than Rio’s Carnaval or New Orleans’ Mardi Gras.[4] But it was still a wild scene. The boardwalk at Paseo Olas Altas filled with laughing people. A parade with florid floats and pretty girls all dolled up. Fireworks erupted throughout the night. Bandas and gruperas played lively music on small stages. Mariachis roamed the streets. Folks carried plastic Coca-Cola bottles containing as much rum as coke. Beer stands on many streetcorners. Lots of drunkenness and a simmering undertone of violence. But Carnaval was mostly a joyous escape from the everyday grind. Young boys and girls flitted about, throwing confetti in each others’ faces as a kind of flirtation. As I awoke the next morning, I was still shaking colorful bits of paper out of my hair.

On the last day of Carnaval, I decided to move on. That evening, at the height of the festivities, I caught a bus to the train station. Many others seemed to have the same plan – the bus was jam-packed, not another person could’ve squeezed on. The old vehicle was laboring. Its shocks, such as they were, had been pushed to their limit, the bus scraping bottom whenever it hit a pothole. Making a right turn, it tipped precariously. Everyone was laughing. Finally, the bus just died in the middle of the road, and we all staggered off into the night.

I got directions to the station and continued on foot. When I got there, I leaned my backpack against a pillar to form a backrest and napped a few hours, ignoring the hubbub. At midnight, I caught a train south through Nayarit and then inland, slowly chugging through rugged mountains and teetering over stunning ravines, across Jalisco toward Guadalajara, where I hope to resolve my passport problems.

Footnotes:

[1] One night, Tony, his friend Lynn, and I dropped acid, hopped in his VW Bug, drove west into Saguaro National Park, and wandered among the strange desert cacti – saguaro, jumping cholla, prickly pear, fishhook barrel – until we were hopelessly lost and howling with the coyotes at low-flying planes.

[2] When I read Jon Krakauer’s book Into the Wild and watched Sean Penn’s movie adaptation and listened to Eddie Vedder’s soundtrack, I identified with Chris McCandless’s amazing and tragic journey, undertaken ten years after this (1990-1992).

[3] The Devil’s Drawer, a Special Biosphere Reserve.

[4] However, it’s true that at Mazatlán’s 2017 Carnaval, Sinaloa’s Secretariat of Health distributed 80,000 condoms to combat the spread of STDs.

On the Road in 1980, Part 1

Mission Dolores Park on the western edge of the Mission District, San Franciso

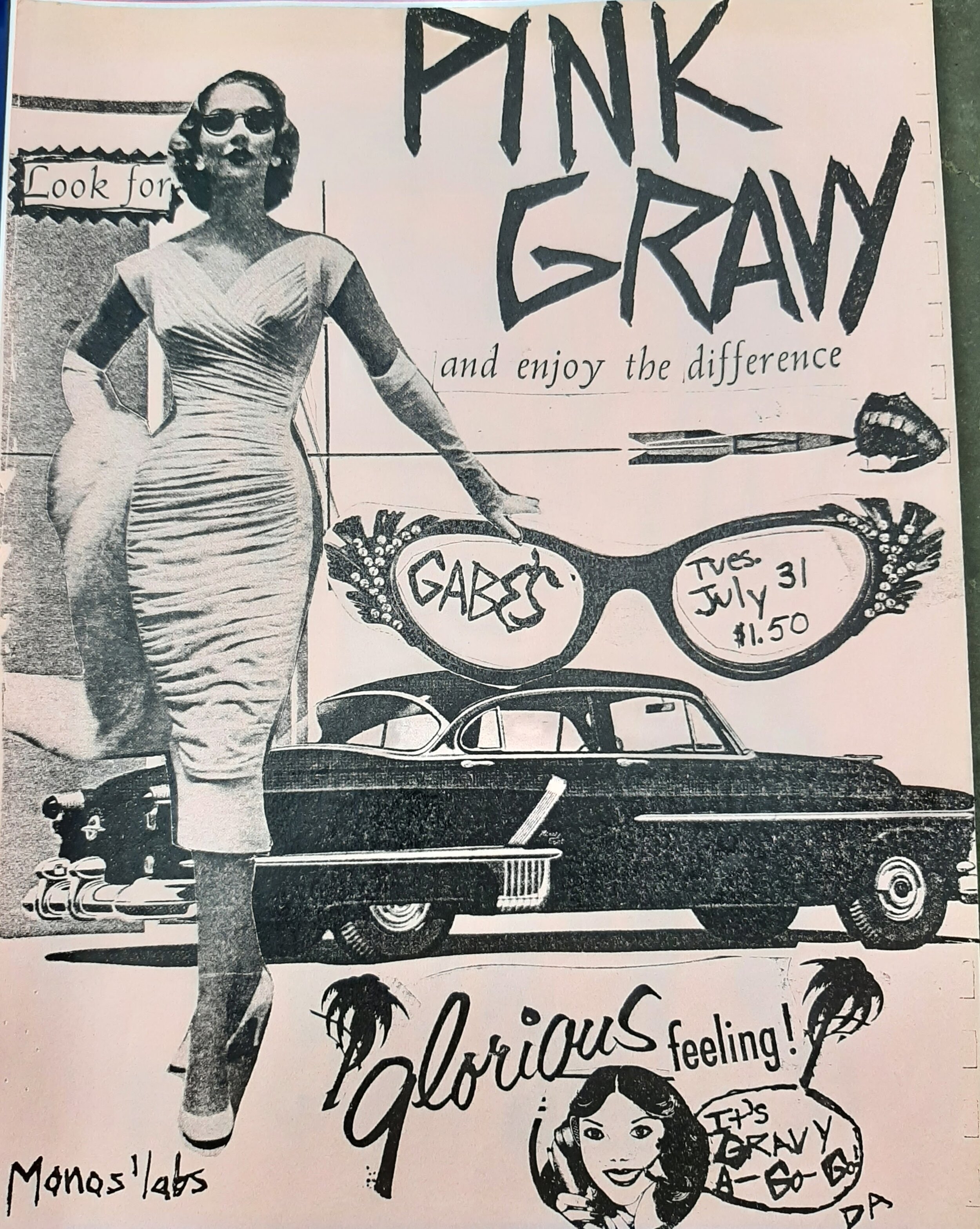

After an exhilarating year performing with Pink Gravy and the Eggthings, I ducked out of the local rock ’n’ roll limelight to hit the road again. My plan was to return to Mexico and go farther south this time into Central America. The semester before I left, I took classes in Intensive Spanish and Ethnology of Mesoamerica to prepare myself. This trip also put on hold a slow-developing relationship with Pat and her son Sierra, who would turn two in a month. Pat and I toggled back and forth between being good friends and lovers. I would sidle up to the idea of entering a committed relationship, but then my attention would be diverted. I was smitten with a cute, quirky, blonde-haired girl[1] in our Undergraduate Poetry Workshop class, Theresa Love (yeah, hard to make up a name more apt), who would leave me handwritten notes: “Meet me at four o’clock by the nut butters at the co-op.” Pat dismissively referred to her as “Jams & Jellies.” I didn’t leave Iowa City on a drizzly overcast January day[2] to extricate myself from this messy love triangle, but I was admittedly over my head and welcomed the chance to step back a bit.

Four days later, I was in one of my favorite cities, San Francisco, on a beautiful warm Saturday morning. I was drinking coffee in Jim’s Donut Shop on the corner of Mission and 29th, all the lively street traffic brushing past my shoulder on the other side of the plate glass window. I basked in the sun, marveling at the strange and unlikely happenstances of life.

An hour earlier, I had been walking up Mission Street, smiling and digging the sunshine vibes, when I was attracted by a low whistle from a cab driver across a busy pocket park. I walked over and began talking with Karen, an attractive Black cabbie who, in a seductively husky voice, invited me to climb in and go for a ride. Without a thought – my mind as foggy as those of the Greek sailors enchanted by the sirens’ song – I did, and we did. An hour later, Karen was dropping me off at that same little park on Mission, a cab ride I’d never forget. She gave me her phone number – still legible in my travel journal in her neatly penciled handwriting – but I never did call her. Not sure why, perhaps I didn’t want to sully the serendipity of that moment with something intentional or anticipated.

In that booth at Jim’s Donut Shop, I took my first deep relaxing breaths since I’d left Iowa City. I’d been planning to head south on I-35, but when you get on the merry-go-round, you grab the ring, no matter where it takes you. I’d grabbed a two-day, 1,400-mile ride from Des Moines to Winnemucca, through the cold high Wyoming Rockies and the barren Utah and Nevada expanses. My companion for this long stretch, libertarian Dennis from Oregon, shared the sleeping accommodations of his van when we’d stop for the night. By Thursday night I had made it from Winnemucca to rainy Reno. I walked into a glitzy neon casino near the highway, sat down at the bar to have a beer, my backpack leaning against the barstool, and before long was befriended by Chuck, a middle-aged guy who offered me a warm, dry place to crash for the night. Ignoring my misgivings, I accepted his offer and, for the next seven or eight hours, held off Chuck’s relentless advances, patiently explaining that I didn’t swing that way, trying to catch a few winks in between. Afterward, I wondered whether I should’ve just let him have his way with me so I could get some decent sleep, but I don’t think I was comfortable enough with myself and my sexuality to do that.

Chuck did drive me out to the I-80 entrance ramp the next morning, my “virginity” intact, and I soon caught a ride through Donner Pass and into the verdant Promised Land of California. When I got to San Francisco, I looked up my old high school buddy Michael, who was living in the Mission District, working and student-teaching. I would end up spending nearly a week there, talking about life and literature with Michael, hanging out with him and his friend Abbe, wandering around the city, and writing in my journal. Looking through that journal, I was intrigued to read this preface of sorts on its second page:

I’m not interested in documenting the visible events of this journey as much as what’s going on inside, the interior voyage. To write when I have the time and urge, to explore my feelings and emotions, to trace that path. But also to celebrate the simplicity of life as it happens, not to lose myself down metaphysical rabbit holes. To combine musings and prose, the mundane and the spiritual. And to be honest and straightforward.

I was setting a high bar for myself, but I’d done enough traveling by this point in my life to know I needed a challenge to make this journey meaningful. Riding a streetcar to Golden Gate Park, I overheard a conversation between two young punks, decked out in leather, studs, and spikes. One said, as we passed through Haight-Ashbury, “This is where the whole flower-child thing started. My parents were here in the middle of it.” Thus, the punks as offspring of the hippie movement, both continuing it and trashing it.

Another day, I kicked back on a slope in Mission Dolores Park, waiting for the sun to warm up the city and clear the fog to reveal a far view of the towering monuments of downtown commerce, occasionally the horn blasts of container ships steaming in and out of San Francisco Bay, nearby the clacking of trolley cars. The Beaux Arts bell tower and facade of Mission High School, the gaudy rows of Victorian houses. Children playing in the park, mothers and fathers keeping an eye, joggers getting exercise, dogs walking their owners, old men with burlap sacks poking through trash, teens drinking beer from paper bags, sleepers in repose on benches, others reading or thinking or observing. Palm trees, walls covered with graffiti, Free Puerto Rico, CIA Killed Angel, a statue of Don Miguel Hidalgo, leader of the Mexican War of Independence. The intimacy of living in close contact with all this. I opened my arms to the city and embraced what it had to offer. “I’m ready to give everything for anything I take.”

I wanted to become sharp, my senses ready, prepared to react, not wasting energy trying to place myself in the center of what was happening. At that moment the earth moved, buildings rocked and rolled, reminding me of the crazy geological pressure we were sitting atop, that political fissure, that fault. I could feel the urge – it was time to move on, see something new, meet people I’d never met, feel something I’d never felt, speak something other than English – time to continue the journey.

Footnotes:

[1] See Manic Pixie Dream Girl

[2] January 15, 1980

My Days in a Rock ’n’ Roll Band, Part 2

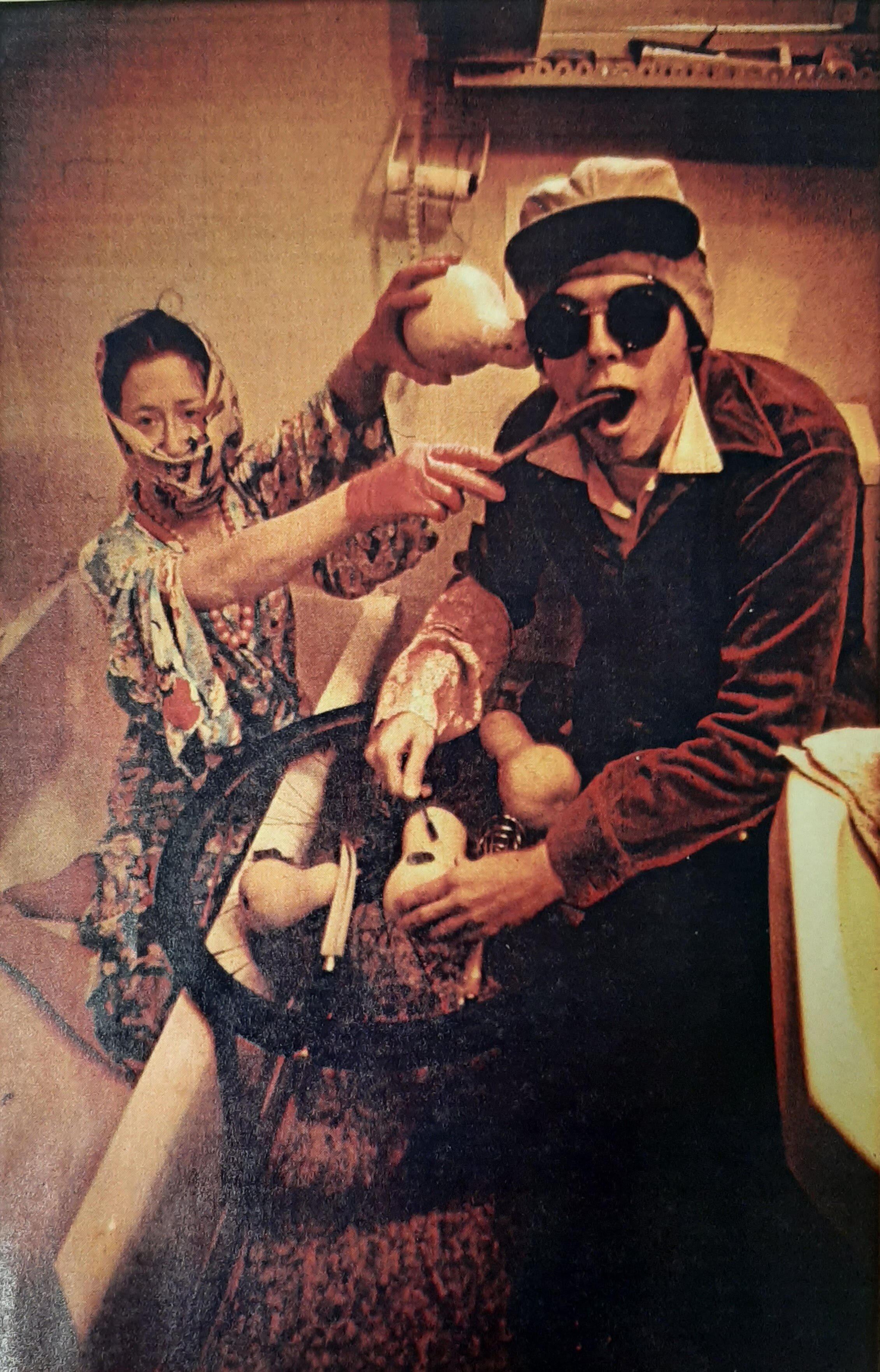

If we’d ever made an album, this could’ve been the cover art. Cf. the Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow album cover.

… or, How I Became a Monos’lab [1]

1979 was an interesting year to be listening to the latest music. That summer, Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park in Chicago signalled the beginning of the slow demise of that musical genre. Punk music had been banging its head against the wall of that sound. New music coming out that year certainly had punk leanings but had also moved on. In 1978-79 we were listening to the debut or second albums from the B-52s, Devo, Talking Heads, Prince, Gang of Four, Pere Ubu, Elvis Costello and the Attractions. This music had energy and vitality. It was raucous but also honored the beat. It felt smart and fresh, ready to both take on and make fun of the world.

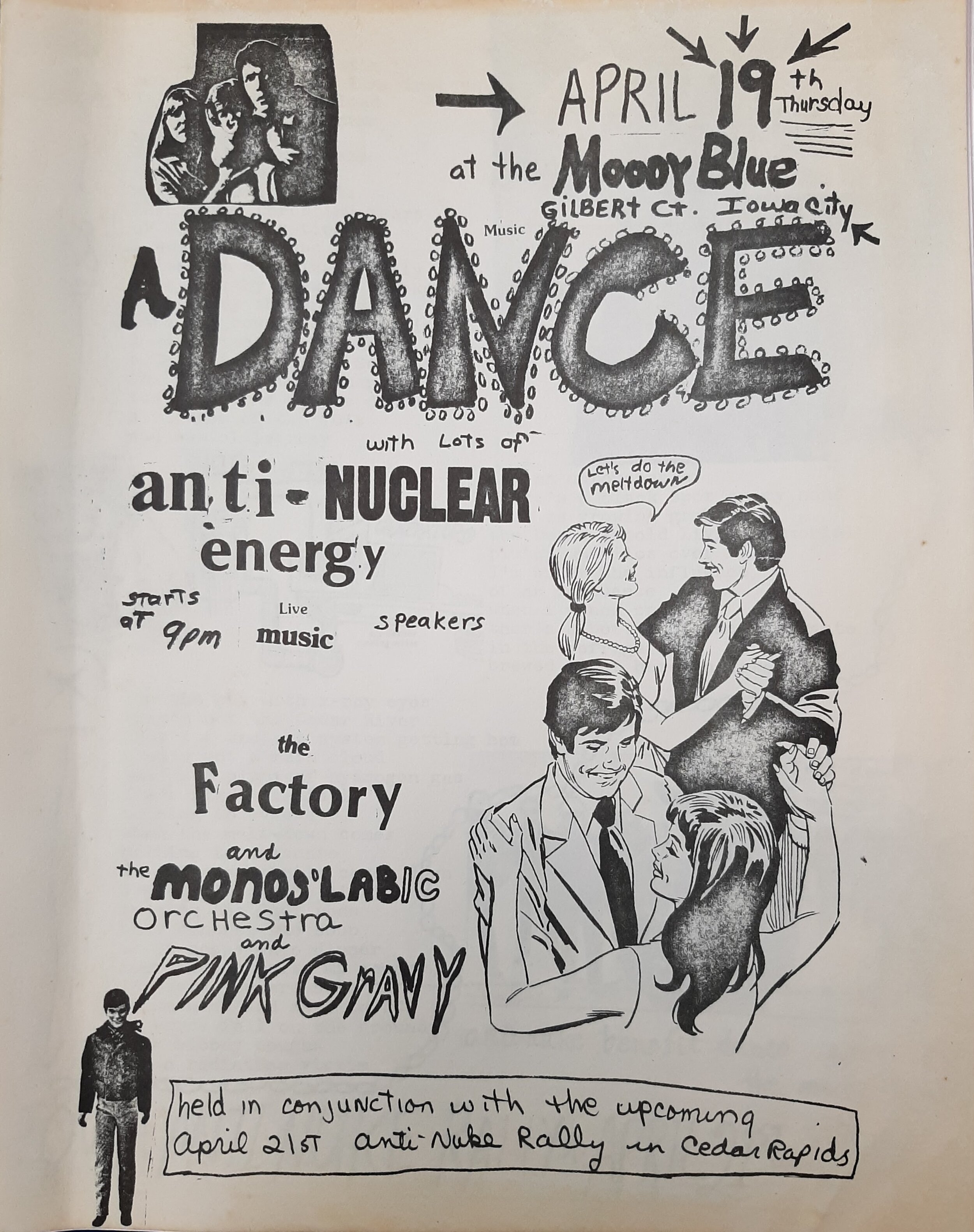

That year, in Iowa City, our newly formed band, Pink Gravy, was vibrating with creative energy, and our small nascent fan base was eager to hear and see what we would come up with next. [2] On September 22, we played one of our most interesting gigs: an outdoor show as part of Iowa City’s dedication of its new ped mall, four downtown city blocks converted from car traffic to foot traffic. We set up our stage by the new fountain at the center of the mall, within a stone’s throw of a half-dozen bars. The show took place on Saturday night after the annual Iowa-Iowa State rivalry football game. Football fans, some still drunk from pre-game tailgating, were hitting the bars hard. Almost everyone was wearing their colors – their fierce alliance represented by either the bumblebee black-and-gold of the Iowa Hawkeyes or the cardinal-and-gold of the Iowa State Cyclones. It was an uneasy commingling of warring camps.

And our band of sarcastic misfits and agitators was in the middle of it. We might cover Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking” or Graham Nash’s “Our House” to appease the audience, but by the time we’d finished mutating those songs, they were barely recognizable. We attracted a range of baffled looks and blurry heckling, and tolerated an incident involving “drunken fools who happened to climb into the fountain and spray the crowd with water [and] damaged the public address system,” [3] but we managed to give as good as we got. Our dumbfounded audience was invited to consider the possibilities that we were due for a “Nuclear Accident,” that it was “Eggtime,” that “Everybody Is a Monos’lab.”

When we played the Beaux Arts Costume Ball at Maxwell’s on October 29, Thomascyne decided to alter our performance wear. Since the audience would be in costumes, she made long pink hooded robes to replace our usually outlandish stage outfits. We looked vaguely liturgical, like nine monos’labic monks. By early December we had earned a two-night weekend show at Gabe’s, which would always be our favorite place to play.

We merged these new sounds we were hearing with the older music we loved. We each shared our personal favorites with the rest of the band: The Velvet Underground, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band, Patti Smith, Bob Marley and the Wailers, Fela Kuti and Africa 70. I kept checking out the double album An Evening with Wild Man Fischer from the Iowa City Public Library. To annotate the quality of the vinyl discs, a librarian had dutifully but aptly and perhaps facetiously affixed a warning label: “Warped But Playable.”

Many wanted to categorize us as new wave, a catch-all term bandied about to explain whatever was coming after disco and punk. We adamantly rejected any attempt to pigeonhole us. Everybody in the band was writing songs – at least fifty in the first two years of the band – and we all explored our favorite musical styles. The blues were represented by “Boinger Man” and “Middle Class Honkie Blues.” [4] Reggae and ska with “Nuclear Accident” and “Gangrene.” Punk with “Fab Con Men” and “I Wanna Be Your Toto, Dorothy.” Country and western with “Goodwill Store.” California surf music with “Iowa Wave.” Doo-wop with “I Like Ike.” Calypso with “Bio” (a remake of Harry Belafonte’s “Day-O” that explains the simple pleasures of selling one’s plasma). All these songs were homages to genres that had influenced us, but our flair for musical shape-shifting also dissuaded listeners from trying to define us.

There was so much that I loved about performing with Pink Gravy and participating in other Monos’labic sabotage. I loved having the opportunity to collaborate with a group of creative people. We leaned on and learned from each other when composing or refining songs, lots of co-writing of both lyrics and music. Inspired by the band’s protests at the Duane Arnold nuclear power plant, I had written the poem “Emotional Data,” which the band managed to turn into a song with a brutal driving beat and a call-and-response singing approach between me and Thomascyne and Brenda. Here are some of the lyrics:

D: I’m the guy with the x-ray eyes

T/B: That’s not the Cedar River

D: That’s a coolant system getting hot

T/B: That’s not a rain cloud

D: That’s a plume of hydrogen gas

T/B: I’m a fixed statistic

D: Nothing to evacuate

T/B: When the meltdown comes

D: Woah! Nothing to evacuate

T/B: With the stockpile comes down

D: I’m afraid of the light

The song featured a long instrumental breakdown in the middle that sounded like industrial noise. This became the signal for all available band members and every brave soul in the bar to do the song’s signature dance, The Meltdown, which entailed slowly descending to the floor and writhing amongst each other in the most congenial of ways – part mosh pit, part hippie love-in.

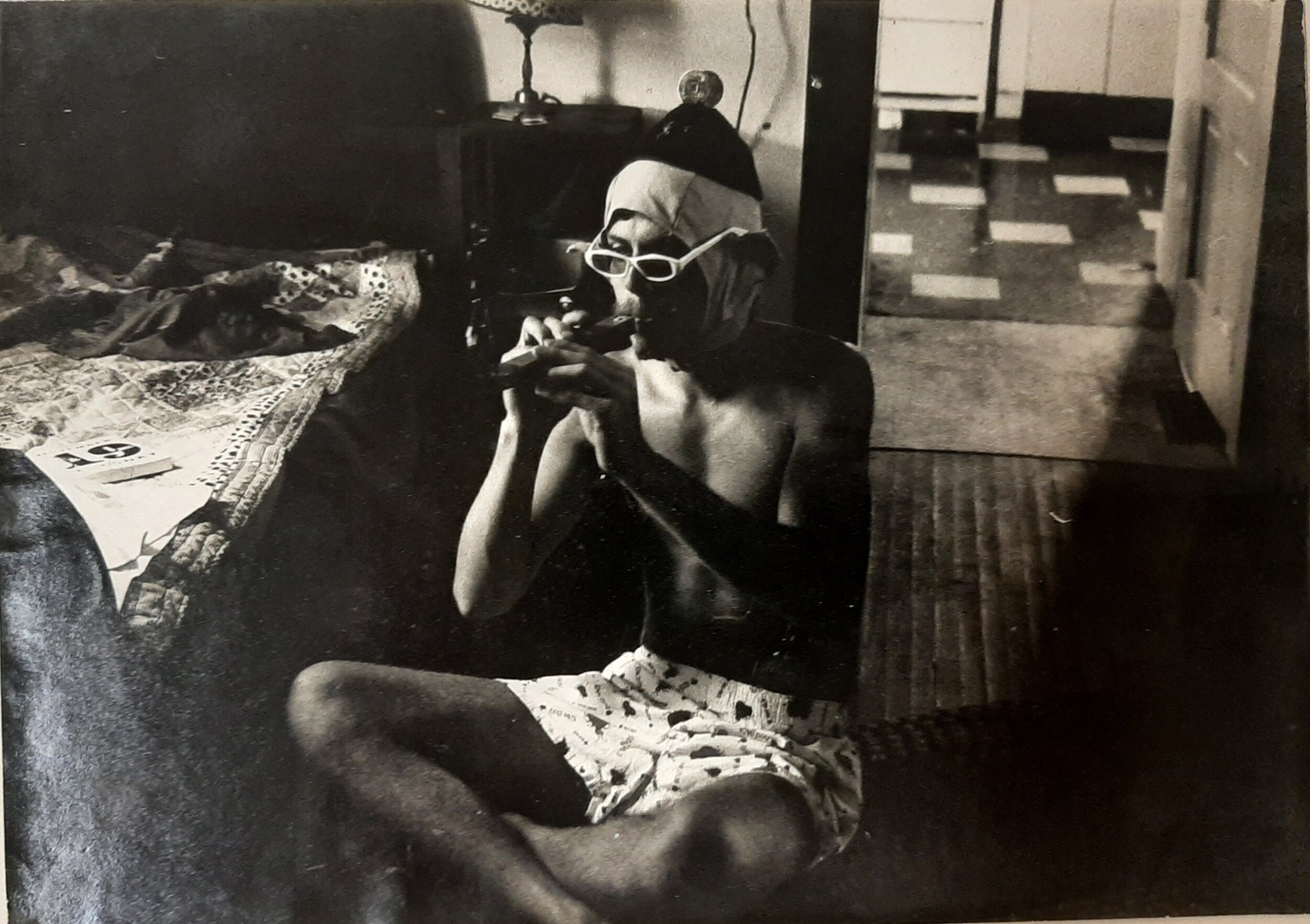

Doing the Meltdown on the dance floor at Gabe’s.

I loved the dopamine high of performing in front of a raucous audience. I loved singing “Rock ’n’ Roll Nun.” [5] We all had stage names for our Pink Gravy personas: Louise and Thelma Swank, Phil Dirt, Dr. Ben Gay, Bob Quinze, Bert the Intellectual Cowboy, St. Orlando, David Ben Sunny. I might be introduced as Physical Ed or Johnny Brandex or Kid Karnage, all depending on the moment. That, along with our stage outfits, functioned as disguises so we could fabricate semi-porous boundaries between our performative lives and our more prosaic daytime lives.

This and the previous photo are by Steve Zavodny, The Daily Iowan.

I loved the way we were able to slip onto public platforms to make fun of the idiot world around us. In 1980, during the heat of the presidential campaign, David Tholfsen and I concocted a side project called the David Convention. Faced with a choice between a Georgia peanut farmer incumbent and a Hollywood movie star, we fought to add an option to vote for David – any David. I recall running around the campus Pentacrest during a noon hour in a pink polyester sport coat, hollering, cajoling students to vote for David. At a Pink Gravy gig at the Crow’s Nest on November 1, we held the David Convention. David and I famously performed an acapella medley of our favorite Wild Man Fischer songs. Quite a few other Davids were there.

Yeah, the Daily Iowan ad actually said “Miller Time,” our shameless promo for Miller High Life. But we never turned down free publicity. Photo by Dom Franco.

I did take breaks from the band to travel – the first five months of 1980 in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. The band continued to perform with great energy. In a rather charming documentary of the band, some of the best videos were shot while I was gone. When I returned from a summer-long 1981 journey through Europe, both the band and I had moved on. But our parting of ways was amicable. Pink Gravy dispersed in that centrifugal way typical of our time – to Lee County, Iowa; Bloomington, Indiana; New York City; Phoenix; Portland, Oregon; San Francisco. Some of us have formed new bands; our first drummer earned a doctorate in musical anthropology; one of us plays Irish traditional music. I’m still here, holding the gifts I gained from the experience – a clearer recognition of myself as a poet, the joy of creative collaboration, the liberating craziness of spontaneous performance – gifts that would quietly resonate in other chapters of my life.

Footnotes:

[1] From Part 1: The Monos’labs were parodies of clueless inarticulate suburbanites, Dick Nixon’s Silent Majority, who would then flock to vote for Reagan. Seemingly unable to fight the rising tide of conservatism, the Monos’labs chose to cynically and satirically infiltrate it.

[2] See “Why Are These People Acting Stupid?” by J. Christenson, The Daily Iowan, November 11, 1979, pp. 1A, 4A, 5A. http://dailyiowan.lib.uiowa.edu/DI/1979/di1979-11-08.pdf

[3] From a Viewpoints letter published in The Daily Iowan, Bill Case, October 4, 1979.

[4] Although I’m unable to link any of the sound recordings we have of our music, our collection of live recordings is in the process of being digitized for the Pink Gravy and Monos’labs archive being curated by the University of Iowa Special Collections folks.

[5] Who wouldn’t enjoy singing, “Here comes the fire chief / Oh, here comes the fire chief / With his red helmet and damaged brain cells / He’s just seen a rock ’n’ roll nun / But a couple a days in the electric chair oughtta set him straight”?

On Quests, Part 2

From The Green Knight (2021), Dev Patel as Gawain and Alicia Vikander as the Lady of the Castle.

“Writing has always been a way to reconcile my lived experiences with the narratives available to describe it (or lack thereof).” –Melissa Febos, Girlhood

That week with Bobbie, we talked about everything. Mornings after Jeff left for work and evenings after dinner, Bobbie and I would take her dog, Gertie Bell, on long walks steeped in conversation. Wednesday, we drove down to Fire Island, part of the barrier chain guarding Long Island’s south shore. We walked along the beach and then picnicked at one of the sanctioned swimming areas. All told, we walked, and talked, over nine miles that day. Thursday morning, we bustled around the kitchen, making lunch for the social studies teachers’ book club Bobbie belongs to; I contributed a Spanish tortilla and helped her make panzanella and another salad. Bobbie had let me know beforehand what book they were reading so I could participate in the discussion.

Friday morning, we swam at the beach near her house and then ran errands in preparation for Family Day, an event hosted by the Huntington Beach Community Association, in which Jeff plays an active role. Bobbie and Jeff’s oldest son, Ben, and his wife and their two children arrived that evening. Saturday was Family Day – neighbors gathering at the beach for fellowship, friendly athletic contests, and lunch. Jeff recruited me to help grill burgers and dogs, and asked me to pair up with Bobbie for the final event, the egg toss competition, while he sought out another partner.

Our long talks included topics we’d covered in our letters, because talking about them in person is different – our hopes and fears for our children and grandchildren, chapters from the stories of our marriages. Bobbie expressed some of the frustrations anyone who’s been married for three or four decades feels when the dynamics of the relationship get predictable because each person takes the other for granted. I vouched for Jeff – he is reliable and generous, I proposed, a good man, a good father and grandfather, a good husband. Bobbie agreed all that was true.

After taking my leave early Sunday morning,[1] as I drove down the Jersey Turnpike and the Eastern Shore toward Virginia Beach, I thought about those five days with Bobbie – what a gift it was to renew our friendship. I was amazed that everything about her that I loved in 1972 is still there in 2021. But I also had this odd feeling of pride in how I’d handled myself (or how we’d handled ourselves). After our first walk around the neighborhood, we’d held each other in a long sweet embrace. And as we would walk and talk, we often brushed shoulders and arms as I’d leaned in to listen better. But that was the extent of our physical intimacy. We instead expressed those feelings by simply being attentive to each other’s needs and moods. I have no doubt Jeff picked up on our mutual affection but, as a kindness, allowed space for it without comment.

In The Green Knight, Gawain, exhausted by his journey and stripped of his horse and all his possessions except the battleaxe the Green Knight had given him, arrives at a castle and collapses in its doorway. We next see him sleeping in a comfortable bed, tended to by the lord of the castle. The lord tells him he will go out every day to hunt and bring home meat to give Gawain strength so he can complete his quest. While he’s out hunting, the lady of the castle attempts to seduce Gawain, testing his chivalry and moral virtue. Her advances repeatedly rebuffed, she instead gives him her green sash, a charm to protect him from harm. I’m not suggesting a perfect analogy between the Arthurian legend and my story – Bobbie certainly never tried to seduce me – but the similarities are uncanny.

When I talked with Bobbie again on my way back to Iowa, she mentioned that Jeff had resumed going on those long walks with her and Gertie. Perhaps seeing Bobbie the way I saw her had given him a renewed appreciation of her. Perhaps my attention to Bobbie had made her glow in a way that enhanced her beauty. Perhaps my visit had helped them find a little more happiness in their life. Oh, I was pleased with my supposed achievement, probably too pleased, but at least I had a legend to explain it all.

That last homeward hour on I-80, which I could nearly drive blindfolded, I catalogued memories of the journey. The hospitality and generosity of Jon and Kathy. The time spent with them and other friends I’d grown up with, folks I’d looked up to when I was a lost high school freshman trying to figure out who I wanted to become. Camping with Emma, Oscar, and Linus in the Virginia sand dunes, among Live Oaks and Scrub Pines. Hiking with them through freshwater swamps filled with turtles, Bald Cypress knees jutting up from tannin-brown waters, the air thick with Spanish Moss, impressive dragonflies, and the plunking, ricocheting calls of bullfrogs. And those perambulatory tête-à-têtes with Bobbie. The culinary duet we performed the morning before the book club meeting. The way I was welcomed into her and Jeff’s family, as if a place had been saved for me all along.

I now sense that, more than ever, I’m on a cusp, my momentum propelling me forward, keen to embrace a feeling not felt since my wife died almost three years ago, something I wasn’t sure I’d ever feel again – that feeling at the beginning of love, that feeling of “When will I see you again?” Could it be that my love for Bobbie makes me more receptive to love from other sources? Is this some kind of reward for “my gallantry”? I know life doesn’t work that way, and honestly, being ready for love – in a world riven with woe – that alone is enough.

8 September 2021

Footnote

[1] Bearing Bobbie’s parting gifts of a half-dozen books, garden produce, and a fresh-baked loaf of blueberry bread.

On Quests, Part 1

Translated by J.R.R. Tolkien, among others, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was written by an unknown 14th-century poet of the West Midlands of England. .

As I recently watched The Green Knight, based on the Arthurian legend Sir Gawain and The Green Knight, one scene resonated for me as I sensed the extent to which it mirrored my recent experiences with my friend Bobbie. The movie is a faithful retelling of the fourteenth-century chivalric romance, with chapter titles in Old English blackletter and a soundtrack that is positively eerie, sometimes sounding like a chorus of Tuvan throat singers. King Arthur is old and doddering; Queen Guinevere is decidedly unlovely; Sir Gawain is a youthful goof-off.

The story centers around Gawain’s quest to fulfill a Christmas Day promise to seek out the Green Knight one year hence, whereupon Gawain would receive the same blow he chose to deliver to the Green Knight. (Gawain had cut off his head, likely not expecting the Green Knight to pick it up as he laughed and rode away.) Gawain’s journey is infused with magic – a woman who asks him to retrieve her head from the bottom of a lake, a talking fox that befriends him, the Green Knight himself, more vegetation than human.

Last October, I was working on a memoir piece about falling in love with Bobbie the summer after high school.[1] Those recollections of first love inspired me to reach out, if only to thank her for all she gave me. I sent a letter, a shot in the dark, to the Long Island address I had for her when our correspondence was sidetracked over forty years ago by growing families commanding our full time and attention. My letter did reach her, and a week later I received one in return, eight pages on yellow legal pad paper. All that catching up!

Although we exchanged emails and cell phone numbers, we decided to continue to correspond via handwritten letters. Over this past year, one of us has received a letter from the other every ten days or so, the U.S. Post Office’s lack of delivery speed giving us time to think of something new to write about, although that was never really a problem. We had a lot to share about our lives and families, about the dismal state of the “American experiment,” about our experiences as high school teachers. We had both left secure jobs in our late forties, returned to school to earn education degrees, and then helped students learn about World History (Bobbie) and Language Arts (me). We would have been great colleagues, our teaching philosophies matched so well.

In May, while I was visiting old hometown friends in Akron, Bobbie sent me a text: “Cheryl told me you are there today and tomorrow. Hope your visit is wonderful. If you get sleepy as you drive back to Iowa, give me a call. I’d be happy to help some of the miles pass.” I had other stops before returning, but ten days later, I texted Bobbie from the first rest stop in Illinois to see if she was available to talk. Back on the road, ten minutes later, I got a call from her: “Where are you?” “Just east of Champaign.” “Well, turn around! I’m in the middle of Pennsylvania on my way to Ohio.”

I was momentarily tempted to do so but decided to continue homeward. Instead, we talked – for the first time in all those years, for over two hours as we both drove west. The miles flew by. We agreed that since we’d missed this chance to meet up, we must do so soon, and I told her I’d be coming back east in August to camp with my daughter and grandsons in Virginia. When we finally said goodbye, as Bobbie was pulling into a rest stop and I was crossing the Mississippi River, she said, “I love you.” Without a moment’s hesitation I responded, “I love you too, Bobbie.”

We made plans: I’d visit her on Long Island at the beginning of August before heading down the coast to meet Emma, Oscar, and Linus at a state park near Virginia Beach.[2] I stopped in Akron for a few days, then drove to the middle of Pennsylvania Dutch country, in the foothills of the Alleghenies, where I camped for the night at the all-but-deserted Holiday Pines Campground – for free since the office was closed. The next morning, as I fueled up on the Twilight Diner special, I watched two horse-drawn buggies make their way along the Interstate 80 overpass. I reached New York City at noon, avoiding rush hour traffic, crossing the George Washington Bridge into Manhattan and the Bronx, then across Throgs Neck Bridge to Long Island, pulling up in front of Bobbie’s house an hour later.

It had been 45 years since we’d last seen each other, but we reconnected as if it were yesterday. Of course, all the letters had smoothed out much of the potential awkwardness of the meeting, but we both still felt a twinge of apprehension. After all, we had professed, not in so many words, our love in those letters, letters that I wasn’t sure her husband, Jeff,[3] was fully aware of. When he arrived home that evening from work, he welcomed me without reservation, taking me on a tour of the dovecote that housed his flight of homing pigeons and the chicken coop he’d built for their laying hens. I was given their boys’ old bedroom, a beautiful space with three ribbon windows looking down on Northport Bay and, beyond a narrow neck of land, the Long Island Sound and the far Connecticut shore. Two skylights in the roof let in sunshine filtered through the tall oaks towering over the house. I called it the Treehouse, and there I slept for five nights as Bobbie and Jeff graciously wove me into the fabric of their life.

Footnotes:

[1] For the full story, I invite you to turn to Falling in Love for the First Time (Parts 1-3) in this blog series.

[2] First Landing State Park, at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, where English colonists first arrived in 1607.

[3] Jeff was the boyfriend after me. When I visited Bobbie in Denver near the end of her first year of college (still thinking I was her boyfriend), he helped replace my car’s fuel filter so I could drive back home.

On Wanting to Shampoo You

I’ve been relistening to and reloving Joni Mitchell’s Blue, fifty years in this world. Ah, the sweet pirouettes of her voice. Her lyrics are still fresh; they still speak to me about the yearnings of youth. Even when the words seem to miss, they hit: “I wanna talk to you / I wanna shampoo you / I wanna renew you again and again.” These lines from the album’s opening song, “All I Want,” seem laughable, at best whimsical, except that (as often happens when stuff gets in your head) they took shape for me three times in the past week ‒ in literature, in real life, in memory.

On a westbound train skimming along the northern border of the United States to Seattle, I was reading James Baldwin’s 1962 novel Another Country. In it, he tried to make sense of the many permutations of heterosexual, homosexual, and interracial love and relationships, such as this: “Yves ... preferred long scalding baths, with newspapers, cigarettes, and whiskey on a chair next to the bathtub, and with Eric nearby to talk to, to shampoo his hair, and to scrub his back.”

The title of Joni’s song is rich with ambiguity. Is this the apologetic, self-effacing “all I want …” or the unreserved, exacting, full-throated “ALL I WANT!” or both at once? The young British singer-songwriter Arlo Parks said, “What I love so much about this song is that it is full of contradiction and conflict. There’s a real sense of exploring what it means to be present and alive in the moment…. It feels like she was trying to hold onto something or keep up with something.” At the end of the first stanza, when Joni entices her listener, “Well, come on!” I am ready to do whatever that means.

While visiting my oldest son, Sierra, and his partner in Seattle, we took the ferry to Bainbridge Island one day for the pleasure of crossing Puget Sound. He had pointed out that because of the high cost of housing in Seattle and its avid backpacking and camping ethos, many homeless people live under highway overpasses but in top-quality tents.

At a sink

in the men’s bathroom

in the ferry terminal

on the Seattle waterfront

one guy shampoos

another guy’s hair

As I wash my hands

at an adjacent sink

the shampooer turns to me

and says, “How’s life

in the real world?”

Finally, Joni’s lyrics brought to mind the times I helped bathe my wife, Pat, over the last year of her life. Drawing the bath water, helping to remove her shoes and clothes, supporting her as she stepped into the tub. Then pouring a pitcher of water over her head ‒ the water cascading down and glinting in the morning light ‒ and shampooing her hair, momentarily lost in the minty smell and thick luxurious foam. Then one more submersion, carefully rinsing her hair, using my left hand to protect her eyes from the stinging suds. And after that, lathering a washcloth to massage her back, neck, arms, breasts, belly, genitals, legs, feet. A stark reminder of how her body was withering over time, skin more and more loose, muscles more and more lax from disuse.

Pat rarely felt anything other than physical discomfort, if not pain, in her final year, the fentanyl patches and oxycodone her only relief. I tried to make those baths for her a small moment of repose, but I was sometimes less than patient with her, and her crankiness (as much as she’d earned the right to it). At my best, I gave a good performance of selfless giving. At her best, she silently applauded the effort.

In each of these moments, I was reminded how physically intimate the act of shampooing another can be, what a superb example of caregiving it is. As she described her desire to be alive and free with someone, Joni might’ve simply sung, “I wanna make love to you.” Her line is far better.

19 July 2021

My Days in a Rock ‘n’ Roll Band…

or, How I Became a Monos’lab, Part 1

When I returned to Iowa City in late August 1979 from my Cape Breton trip, I was looking for a change. I responded to a roommate-wanted ad on the New Pioneer bulletin board. This small step led me into a world of new friends and collaborators, of artists and musicians and writers, people who looked clear-eyed at the world handed down to them and engaged with that world in the guise of characters, as if it all were a play, and it was.

I met Thomascyne Buckley, a gregarious, auburn-haired art student, at her first-floor apartment in a house on Fairchild Street, and soon moved in with her and her dog Max. They’d been living there a year, and she’d put her stamp on the place. The creative chaos was both exciting and unsettling, but I soon found my footing. Hanging from trees in the backyard were boingers, musical sculptures Thomascyne had made by shaping thick aluminum wire into objects vaguely resembling tight tornado funnels. I would lie in a hammock, reading and absentmindedly strumming the boingers with anything like a drumstick to produce a shimmering and beautifully eerie sound, a coda perhaps to a particularly good poem or paragraph.

As the semester started, what we were each studying and creating led to interesting discussions across disciplines – art, literature, music. Having caught parts of a Dada Conference held at the university back in the spring, we both were drawn to the absurdist sensibilities of Marcel DuChamp, Kurt Schwitters, John Cage, and others. And we were also keeping a close eye on current issues.

In her sculpture class, Thomascyne was constructing “eggthings,” costumes made of wire frames covered in heavyweight gessoed paper, with armholes, legholes, and an eyehole, and a seam between the top and bottom that would allow a person to put it on and wear it. I was intrigued as I watched her work out the practical design issues of making wearable art. Meanwhile, she was constructing a narrative to explain these six eggthings: Dr. Bob was in the lab, messing around with some radioactive materials, when a half-dozen adjacent eggs were accidentally contaminated, mutating into these six-foot-tall eggthings.[1]

At that time, most politicians thought nuclear energy was the solution to our need for a cheap and unlimited alternative to fossil fuels. But others feared nuclear power plants were being approved and built too quickly without regard for their dangers. Those fears were realized in late March of that year when a partial meltdown and radiation leak occurred at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. Thomascyne’s sculptures were whimsically highlighting those dangers, critiquing them by normalizing them.

Meanwhile, one of Thomascyne’s sculpture classmates, Brenda Knox, was creating fabric head masks of characters such as Madge and Howard Nelson, Bowlo, Zippy the Pinhead.[2] These characters became model Monos’labs – clueless inarticulate suburbanites on vacation, parodies of Dick Nixon’s Silent Majority, the kind of folks who would flock to vote for Reagan the following year. Brenda and Thomascyne scoured second-hand stores, looking for outlandish outfits for the Monos’labs, the more polyester the better. Seemingly unable to fight the tide of conservatism sweeping the nation, they chose to cynically and satirically infiltrate it.

Other young artists would frequent the Fairchild Street house. Walter Sunday stopped by, lugging a large paper bag filled with combs he had scavenged from the streets. I was taken by his single-minded passion and began to do the same. These are the opening stanzas of my long poem documenting the experience:

Once upon a time, Walter, obsessed with the debris of combs,

casually left a pile of them on our kitchen table.

Black and anonymous, as common as money, they

remained there, an arrangement that lasted through the winter.

Their purpose squandered, never again would they

orchestrate the wave of hair through their fine teeth.

Then the sun returned and the snow melted, disclosing

this residue of combs scattered throughout the city.

Combs on the sidewalk, steaming with ownership,

still holding the private tangled strands of lives.

Combs made of hard rubber, DuPont nylon, all the plastic

brands—Pro, Goody, the ubiquitous black Ace, the Unbreakable …

At the suggestion of Thomascyne and Brenda’s sculpture professor,[3] all this came together as a performance of their work. Thomascyne had recruited a crew of adventurer-participants; all the eggthings were selected for their tall, lanky physiques. She had located a free piano and a pickup truck. That afternoon, we hauled the piano across town while playing it maniacally. And so it began one night in late October, near the UI Art Building, under some trees beside the river, dimly illuminated by the lampposts on the bridge.

This was the debut of the Monos’labic Orchestra. Thomascyne’s tangled tree of boingers made a musical appearance, trash cans provided a percussive element. Six eggthings – all well over six feet tall – danced and whirled and chanted: Moon, stars, planets, boing! … Omm-lette! … Je suis fou! Je suis dans la lune! A sizable crowd of students showed up, curious about what and why. It was all wonderfully messy and funny, but also at times magical and mysterious.

The eggthings were naïve and idealistic, in need of protection from a judgmental world, so we adopted them. Everyone involved in the performance realized this wasn’t over, that some kind of second act was coming. That next act took place on a slushy February day when the six eggthings returned to public life to protest the wholesale slaughter of their brothers and sisters at Hamburg Inn #2, Iowa City’s popular breakfast diner. The entire demonstration was documented – the eggthings picketing in front of Hamburg Inn,[4] a “token woman reporter” interviewing them and inviting them to make an incoherent statement of their concerns, and then a VW van suddenly appearing and a pack of RV people clambering out, chasing off the helpless eggthings, and catching up with the most hapless of them, Sonny Side-Up, across the street. A martyr to the cause, Sonny lost his life that day, his scrambled remains strewn in the alley off Linn Street

A few weeks later, Pink Gravy and the Monos’labic Orchestra performed at the Wheel Room, the bar in the basement of the UI student center. It was both a memorial concert for Sonny Side-Up and a Mardi Gras Festival celebration. Making its first appearance was Pink Gravy, the electric rock band manifestation (or mutation) of the Monos’labs. In the planning leading up this event, scraps of ideas on paper were floating around the Fairchild house kitchen table. On one of them, someone had scrawled “punk group.” Thomascyne walked in and misread it aloud: “Pink Gravy?” The name would stick.

Once again, Thomascyne served as the mastermind and agent provocateur and mother of this venture. Both Brenda and Thomascyne had great voices. Brenda played sax and flute. Thomascyne quickly picked up the electric guitar and sax. Paul added his solid lead guitar and vocals, and Chad became the quintessential quiet, steady bass guitarist. Bob was on drums, Eric on keyboards, and David Tholfsen and I on percussive energy and vocals. Alan, Scott, Kevin, and many others joined in at various times during the life of the band. I was invited to get involved because I was a poet who enjoyed disguising myself in costumes and acting goofy. I sang backup and occasionally lead vocals. I played the tubes[5] and other percussive instruments – squeak toys, boingers, bike horn, smoke alarm, as well as more traditional instruments.

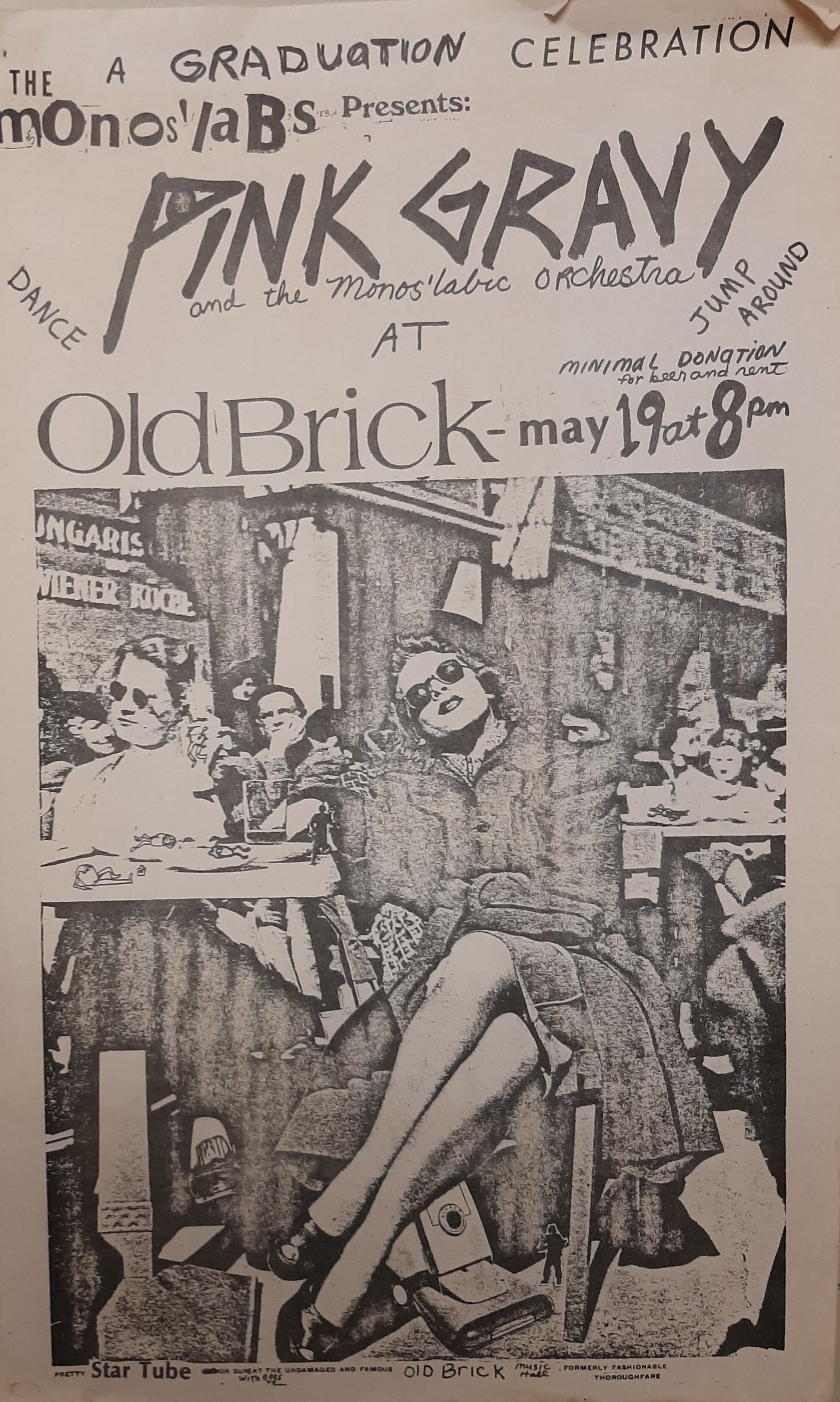

In March, we played the Wheel Room again, and in April, we were at The Moody Blue to rally support for an upcoming demonstration at the Duane Arnold nuclear power plant near Cedar Rapids, where a number of Monos’labs were arrested for trespassing. In May, we rented the Old Brick building for a Graduation Blast featuring Pink Gravy and the Monos’labic Orchestra. Brenda, who worked at Gabe’s, helped us get our foot in that door, and by July, we were playing gigs at what would become our favorite place to play. We publicized our shows by stapling bright, busy collage posters all over town (which fans would then remove because they liked the art). Much of the raw material for the posters came from magazines of the fifties, a bonus of our second-hand store scavenging. We mastered the art of xerox, sometimes making copies of copies so that the image degraded, generation by generation.

How does one explain this? We were a bunch of bored and restless kids who decided to do whatever we could to shake up the status quo, to épater les bourgeois.[6] The recipe: stir up a couple of visual artists, some writers, a few musicians, and shake vigorously, garnish with Monos’labs and eggthings. The end result was a conceptual garage band (or warehouse band since we practiced at Blooming Prairie Warehouse) that was visually interesting and musically all over the place. People came to see the spectacle, listen to our songs, and dance with us. For me, hanging with this group of people was creatively inspiring and crazy fun. As Pink Gravy would remind us in its ska number “Everybody Is a Monos’lab” – “S’labbin’s happenin’/ It certainly isn’t fattenin’/ You just gotta see it through/ Get some data from the view.”

Footnotes:

[1] According to the song “Eggtime,” by the band Pink Gravy.

[2] Madge with cat-eye sunglasses and severely coiffed hair, Howard looking vaguely academic, Bowlo a pudgy-faced Italian guy, Zippy with an actual rabbit ear TV antenna.

[3] Louise Kramer, a visiting instructor from New York City. The creation of Thomascyne’s boinger pieces had been encouraged by David Dunlap in his drawing class.

[4] One of the picket signs was a real estate yard sign that had been appropriated and mutated: “Dick IcKee real or.”

[5] Rubber shower hose, galvanized iron and PVC plumbing pipes, plastic tubing,

[6] That is, stick it to the man.

How I Came to Iowa City…

Anti-war protest on the University of Iowa Pentacrest, spilling out onto Clinton Street, May 1970

… And Found a Home

My family moved from Stow, Ohio, to Urbandale, Iowa, in 1974, while I was living in Western Kentucky. As I understood the story, my father, a liquor salesman for Seagram’s, took the fall for some company malfeasance involving the Ohio State Liquor Control Board. After he did this, the company got him out of Dodge and into Iowa, and to thank him for his loyalty, handed him a promotion – State Sales Manager. For me, the most salient point of this was I could claim Iowa residency and then pay in-state tuition at the University of Iowa.

While working on my high school senior project – an independent study of modern poetry – I had developed an interest in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. It kept popping up in bios in the back of the anthologies I was avidly perusing, books such as The New American Poetry (1945-1960) and An Anthology of New York Poets. Even though I’d never been to Iowa and had not applied to any colleges, in my yearbook questionnaire I listed the University of Iowa as my post–high school destination. I guess that was aspirational. But when my family moved to Iowa, I realized I could make that come true.

I moved in with my family in December 1974, camping out in the basement utility room, applied to Iowa, and proceeded to land three part-time jobs – working the grill at George’s Chili King on Hickman Road, clerking at an Iowa State Liquor Store on Douglas Avenue, and tending bar at Christopher’s, a family-owned Italian restaurant in the Beaverdale neighborhood. I worked until June, until I had enough money for my first year’s tuition, and then quit all three jobs and took off to Ann Arbor to find out what my good friend Jim “Prch” Prchlik was up to. He was sharing a rambling farmhouse on the edge of the city and making bank by working weekend shifts at the nearby Ford Truck plant. During the week we’d work in the garden and then roll into town to hang out with the street people living on and around The Diag and State Street.

Notable among this shifting lineup of characters were Tom and Whiskey Stone, members of a group of wandering souls who a few years earlier in an encampment outside Austin, Texas, had sworn an oath binding them as the Stone Family.[1] These folks helped me master the arts of panhandling and dumpster diving, not essential life skills for me but part of some socioeconomic experiment: Was it possible to live off the wastefulness and affluence of bourgeois America?

After a few weeks in Ann Arbor, I headed to Iowa City to scope out a place to live that fall. I have a distinct memory of coming into town on a sunny afternoon, walking down Iowa Avenue and noticing the C.O.D. Steam Laundry, a combination deli, bar, and music venue. When I heard The Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’” playing on the sound system, I knew I’d found a home. The inimitable and venerable Gerry Stevenson – in his usual garb of khaki shorts and long-sleeved Oxford shirt, glasses tipped on the end of his nose – served me a beer and a sandwich loaded with alfalfa sprouts.

I spent a couple days scouring the want ads, tracking down leads, knocking on doors, and returning to City Park each night to camp out. I’d found Stone Soup Restaurant and would wash dishes for a free lunch. One of the other dishwashers, Tom Leverett, invited me to a birthday party for Kevin Kelso, who worked at New Pioneer Co-op. Early that evening, I was panhandling spare change for, as I readily explained, a bottle of wine to take to a party. I was standing on the corner of Linn Street and Iowa Avenue, in front of Best Steak House, a restaurant run by two Greek brothers,[2] when my liquor store co-worker friend and his girlfriend Laura knocked on the restaurant window and gestured to come inside and join them. I ended up at a party at Laura’s house that night instead.

I did find a place that fit my budget of under $100 a month rent: a room above a Montessori pre-school on Reno Street with access to the kitchen used by the staff. I liked that it was a good twenty-minute walk from campus, and much closer to Hickory Hill, a large rambling urban park. I came to enjoy that walk home via the back alleys of the Goosetown neighborhood originally settled by Czech immigrants, admiring the tidy backyard gardens and grape arbors.

Across the hall lived the poet John Sjoberg and his cat Liz. John’s door was always open to me, and he became a valuable mentor. In the center of his room sat a typewriter with a roll of teletype paper cascading from it. I could always stop in and read where he had gone in his mind the night before. He was a poet of imagination and love. For example, here’s the opening stanza of his poem “Porch Window”:[3]

my head is green

the songs here, the bird songs

here & here & here

are my heart.

John introduced me to a group of poets, most of whom had graduated from the Writers’ Workshop and settled in the Iowa City area: Allen and Cinda Kornblum, Morty Sklar, Chuck Miller, Dave Morice, Jim Mulac. There was usually a reading on Friday or Saturday night at Alandoni’s Used Book Store at 610 South Dubuque Street,[4] and a party afterward. They called themselves Actualists, a name I always considered facetiously applied but one that recognized a supportive community of writers. The ambiguity of the name allowed room for anyone to fit in, including me, at least five to ten years younger than these other writers.

This decision, along with the decision, within a month after starting school, to take a job working part-time nights at the Stone Soup Restaurant’s bakery, established my roots in two Iowa City communities only loosely connected to the university, roots that made this start to feel like home, a place where I could “sit down and patch my bones.”

Having arranged to move into my place on Reno Street on the first of September, I took off for Madison, crashing a few days in an empty room in a large frat house reinvented as communal housing, and then looped back to Ann Arbor. A week later, Prch suggested I check out the Rainbow Gathering, an annual counterculture festival illegally held on some remote public lands the week of the Fourth of July. According to word on the street, it was happening near Hot Springs, Arkansas, that year. So I “got out of the door and lit out and looked all around.” In northern Arkansas I caught a ride from a NASCAR wannabe going 125 miles an hour down I-55, lakes becoming blurry blue visions, streaks of billboard boastings, flickering fenceposts and rows of cotton. Sporting a burning grin and waving his cigarette at me, he yelled above the noise, “Hot damn! Tomorrow’s our country’s birthday! Let’s torque it up in her honor!” I smiled weakly and held on.

When I got into Hot Springs, I could find no hint of the Gathering. I walked around, looking for anyone letting their freak flag fly who might be able to slip me the secret directions. Nothing. It turned out the Rainbow Gathering was in the Ozark National Forest[5] near Mountain Home, Arkansas, almost 200 miles due north, but I wouldn’t learn that until much later. I got dinner in town and spent the night on the outskirts of Hot Springs, near the road I came in on. Next morning, the Fourth of July, I got a ride from a couple of Arkansas Baptist College football players on their way to a party in Little Rock. They invited me to join their celebration.

When we got to the party, held in an apartment building owned by a team booster, I was goodnaturedly introduced to him and the other football players and their girlfriends as “Yankee.” There was a watermelon loaded with vodka and a tub of Budweisers on ice. Early afternoon, with only a breakfast in my belly, the drinking commenced. I somehow felt the need to defend the Union by keeping pace with these Little Rock secessionists. I lasted a couple of hours, eventually accepting defeat by diving into the apartment building’s pool with my clothes on. My friendly rivals fished me out and helped me to an empty apartment where I could sleep it off. They woke me in the morning, treated me to a hearty breakfast at a local diner, and sent me on my way.

Back on the road, I watched a long slow freight train pulling out of Little Rock. I decided to hop it, but by the time I got to the tracks, its speed had picked up. Running with a backpack on a rocky uneven railroad bed and trying to catch an open boxcar proved a failure. I picked myself up, washed off my scrapes, and proceeded to hitch to Bowling Green, Kentucky, where my friend Pat Berkowetz tended my wounds, physical and otherwise. I then stopped in Akron to see some high school chums before landing back in Ann Arbor. But I was soon back on the road, hitching to Minneapolis with Kelly, and continuing on my own, west to Seattle, down to Oregon and San Francisco, back up to Ashland, Oregon, east to Denver, and finally Iowa City by the end of August.[6]

1975 was a restless year. Like many young Americans, I was searching for something I could trust to be true.[7] When I moved into the room above the Montessori school and started classes that fall, it felt right, like the satisfying sound of a puzzle piece clicking into place. I began to see the possibilities of finding my niche in this Midwestern college town – among a group of poets collaborating, engaging with the world, and celebrating whatever felt real, and among a community of folks creating a cooperative network to offer food that was natural, organic, unspoiled by the corporate world. For all the miles of wandering still ahead of me, perhaps I’d found a fit, a home, a place and people I could return to when I needed a rest.

Footnotes:

[1] For a photo of the three of us, see my blog post Friends of the Devil, Part 2. The daughter of an oil millionaire from Odessa Texas, Whiskey was a high school cheerleader impregnated by the star football player. After her dad denounced her and got a court order granting him sole custody of the child, Whiskey hit the road.

[2] Who would respond to every order by asking, “You want fries with that?”

[3] From John’s book Hazel and Other Poems, published by Allan and Cinda Kornblum’s Toothpaste Press in 1976. His inscription in my copy: “To Dave & the House. May Kentucky always grow in your heart an’ help your head.”

[4] One of the 150-year-old cottages demolished in 2015 over the objections of historic preservationists.

[5] Video trigger warning: hippie nudity.

[6] I described some of the events of this part of the trip in my blog post The Art of Hitchhiking.

[7] The Pentagon Papers (1971) and the Watergate Scandal (1972-74) were just two manifestations of that sense of being betrayed.

People We Used To Be, Part 2

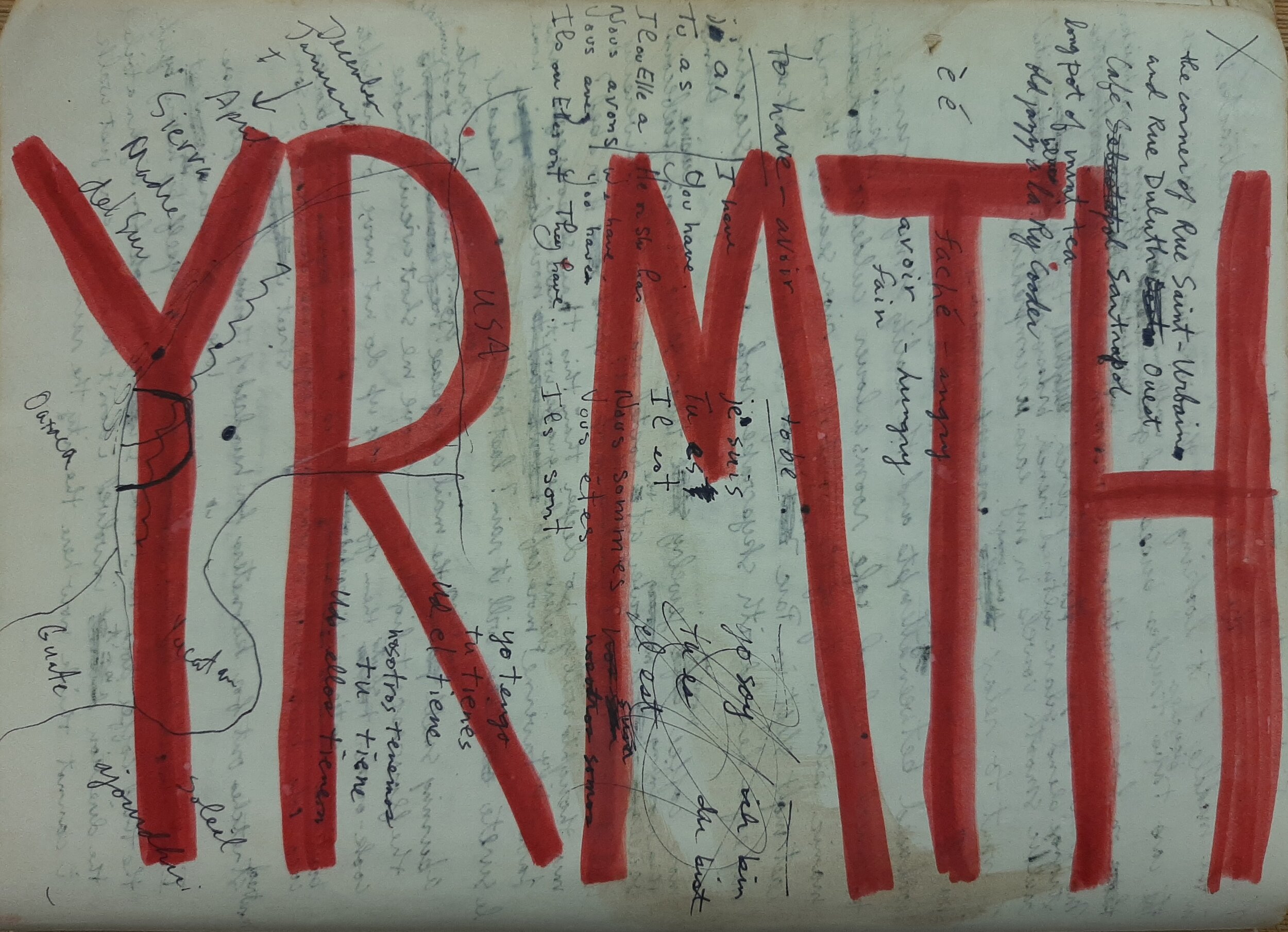

Hitchhiking sign for Yarmouth, from my comp notebook. In the underlayer of text, the conjugation of avoir and etre, most of it in Johanne’s hand. I must’ve been driving.

“Perhaps a person can write about things only when she is no longer the person who experienced them, and that transition is not yet complete. In this sense, a conversion narrative is built into every autobiography; the writer purports to be the one who remembers, who saw, who did, who felt, but the writer is no longer that person. In writing things down, she is reborn.” -Rachel Kushner, “The Hard Crowd: Coming of Age on the Streets of San Francisco”

Bidding farewell to my new friends Johanne and Marc and their cabin in the woods near Mont-Joli, I headed southeast on Highway 132 toward New Brunswick. As I passed through the little eastern Québec towns – Sainte-Flavie, Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici, Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue[1], Sainte-Jeanne-d’Arc, Saint-Noël, Saint-Alexandre-des-Lacs, Sainte-Florence, Saint-François-d’Assise – I thought about the communion of saints, the mystical bond uniting us through hope and love. Was this what I would learn on this journey into the unknown?

When I crossed into New Brunswick, I entered the Maritimes, Canada’s Atlantic coast provinces, originally the home of the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy people, taken over in the early 17th century by British and French settlers. The French settlements were known collectively as Acadie. And my route along the New Brunswick coast – Highway 11 – had been named the Acadian Trail. The rides were short but came as quickly as I desired them to, and the entire southeasterly route from the Québec border through New Brunswick was less than 400 kilometers. As I traveled I could make out Prince Edward Island, ten miles across the Northumberland Strait.

When I crossed into Nova Scotia, I picked up the Trans-Canada Highway again, heading due east and then crossing the narrow Strait of Canso separating Cape Breton Island from the rest of Nova Scotia. I picked up Highway 19, which took me along the northwestern side of the island. As the traffic thinned out and the little towns grew fewer and farther between, I slowed down, enthralled by the romance of the sea and landscape. Sheep grazed the high meadows of yellow clover and lavender, thickets of wild roses, huckleberries, raspberries, leading down to the fishing villages and plummeting into the Northumberland Strait.

A ride dropped me off midday in Margaree Harbour, a picturesque village at the mouth of the Margaree River. I walked around until I found the most popular café. Afterward, hiking across the bridge over the river and out of town, I burst into a spirited song of the road:

Hike a stiff easterly breeze

with a bellyful of fish chowder –

the trawler’s come home with the catch.

Fling yodels off the precipices,

echoing down through the dales.

String the Acadian fiddle, lads!

Blow ye winds on the bagpipes!

Near Chéticamp I entered Cape Breton Highlands National Park, 366 square miles of high plateau and rocky coastlines. No roads led into its heavily wooded interior, and the park contained a wealth of wildlife, including lynx, bobcat, moose, black bear, and coyote [2]. Following the Cabot Trail, the road circumnavigating the park, I pushed on to the Highlands, the cloud-hidden spruce, jackpine, and birch reaches through which the Chéticamp River cut a gorge.

Near MacKenzie Point, knowing that the route was about to turn east and inland along the northern boundary of the park, I stopped for the day. Because I hadn’t stocked up on enough provisions to allow for multi-day camping, and the handful of official park campgrounds offered only the most basic tent-camping amenities, I realized this might be the extent of my stay. I followed a short trail to an overlook, and then wandered off that trail for some tent-free camping. From my sojournal:

camp on high cliff overlooking

the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

beyond that Newfoundland,

the Grand Banks,

the North Atlantic.

scrub pine for wind protection,

moss to cushion the bedrock.

quarter moon gives way to

milky stream of stars

to glistening blue sunrise.

Cabot Trail along the northwestern coast of Cape Breton Island

The next morning, I scrounged up a couple of apples and a hunk of cheese from my rucksack and sliced it all up for a little breakfast plate. I’d been on the road for almost twenty days and hitchhiked over 2,000 miles to arrive at this beautiful morning in this spectacular place. And that was it. That was all I needed or wanted from this trip. From that point on, I was moving in the direction home – across to the eastern side of the island and then south along the coast. I was packing Gary Snyder’s Turtle Island in a pocket of my rucksack, reading and rereading his poems and essays. In “Four Changes,” I’d underlined: “Balance, harmony, humility, growth which is a mutual growth with Redwood and Quail; to be a good member of the great community of living creatures. True affluence in not needing anything.” After camping for the night on a beach, I wrote in my notebook:

driftwood and smooth beach stones

are ideal for campfire cooking.

boil brook water

add five hands

of rolled oats

stir until thick

mix in honey, raisins, sunflower seeds

rich helping of peanut butter.

this

will last until midafternoon.

After stepping off Cape Breton Island, I continued along the southeastern coast of Nova Scotia, small fishing ports anchored to the rugged coastline, interrupted by Halifax, the only substantial city in the province. The white horses of the surf raced along, the ocean tossing tangles of rigging and mislaid lobster traps on its shores. Big-boned gulls met up at the cannery docks after following the fishing trawlers home. Little fingers of the ocean curled up into the land, beckoning – Halifax Harbour, St. Margaret’s Bay. The land jutted out its chin where the storms broke and the wind never ceased – Fox Point, Western Head. Across the waves, a white-rocked beacon cast its lonely eye across the ocean, a mother searching for her son, lost, swept away.

I was traveling easily, unhurried, no schedule, no deadline, this time with myself. When I wanted a break from the road, the ocean was never far. Because of the Gulf Stream, the southeast coast of Nova Scotia offered bracing but pleasant waters for swimming:

still cove of rock

shelter from the sea’s turmoil.

cliffside coursing with pink granite

flecked with agate and quartz.

water transparent

twenty feet deep off this edge.

sea tern enters

circles

dives for its meal.

When I reached Yarmouth, at the southern end of Nova Scotia, I took my leave of the Maritimes. I booked passage on the ferry out of Yarmouth Sound, past the Cape Forchu lighthouse, across the Bay of Fundy as the evening fog rolled in – 180 kilometers to Bar Harbor, Maine. I roamed the ship, observing my fellow passengers, stopping at the bar for a Moosehead Ale and a shot of rye whisky. On the stern deck, I met two free-spirited women travelers from Minneapolis and kept their company for the rest of the voyage, sharing their cigarettes, drinking ales and conversing between blasts of the foghorn, falling in love with ballet-bodied, green-eyed Mary – but we kept it friendly. Listening for whale songs through the night, we disembarked at sunrise.

I had one stop to make on my way back home. After graduating from Iowa, my friend Tony Hoagland had moved to Ithaca to test the post-graduate waters of the writing program at Cornell. I took US Highway 2 through the backwoods of Maine and into New Hampshire. Early that afternoon, as I was passing through the White Mountains, ten miles north of Mount Washington, I came upon a cascading mountain stream beside the road. I asked the driver to pull over to let me out, and climbed the hillside, following the stream, until I came to a place where the water pooled beside large basking boulders out of sight of the road. I stripped down and floated in the cool, clear mountain water, high on the wonder of it all, thinking about Tony:

I reached up to draw

the pennyroyal from my ears.

Rushing back came the sound of water.

The river reclined on rock contours,

pocketfuls of coins laughing down its slope,

the sacred chords of silvery promises.

As I lingered, the sun dried thoughts of you on my skin.

One last border to fall before the flints of our souls will strike again.

I continued on Highway 2 into Vermont, then south on I-91 and west into New York State, reaching the Hudson River and Troy by nightfall. By then I was deep into this notion of an epic or mythic odyssey, and scribbled in my journal the next morning: