People We Used To Be, Part 2

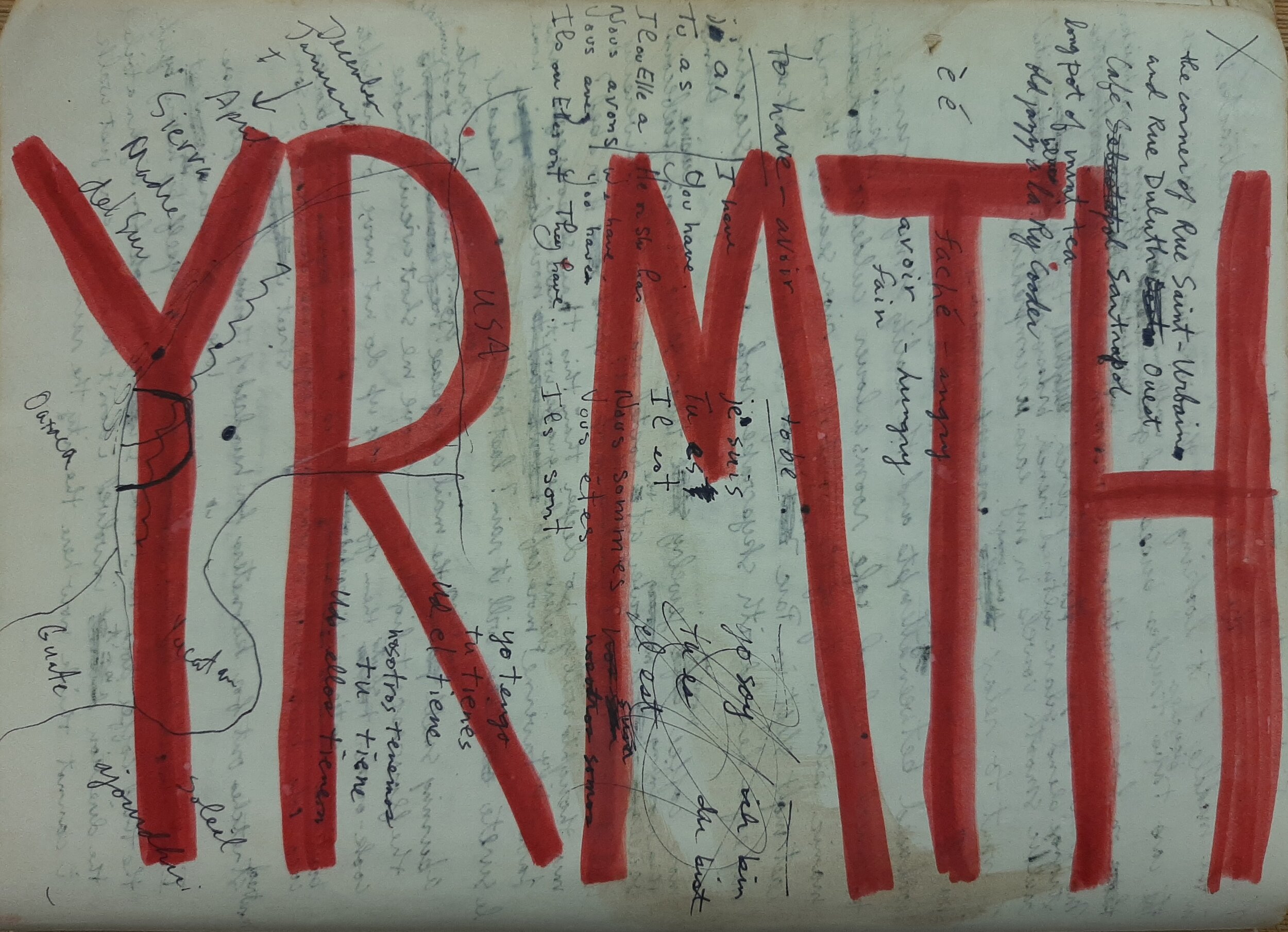

Hitchhiking sign for Yarmouth, from my comp notebook. In the underlayer of text, the conjugation of avoir and etre, most of it in Johanne’s hand. I must’ve been driving.

“Perhaps a person can write about things only when she is no longer the person who experienced them, and that transition is not yet complete. In this sense, a conversion narrative is built into every autobiography; the writer purports to be the one who remembers, who saw, who did, who felt, but the writer is no longer that person. In writing things down, she is reborn.” -Rachel Kushner, “The Hard Crowd: Coming of Age on the Streets of San Francisco”

Bidding farewell to my new friends Johanne and Marc and their cabin in the woods near Mont-Joli, I headed southeast on Highway 132 toward New Brunswick. As I passed through the little eastern Québec towns – Sainte-Flavie, Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici, Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue[1], Sainte-Jeanne-d’Arc, Saint-Noël, Saint-Alexandre-des-Lacs, Sainte-Florence, Saint-François-d’Assise – I thought about the communion of saints, the mystical bond uniting us through hope and love. Was this what I would learn on this journey into the unknown?

When I crossed into New Brunswick, I entered the Maritimes, Canada’s Atlantic coast provinces, originally the home of the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy people, taken over in the early 17th century by British and French settlers. The French settlements were known collectively as Acadie. And my route along the New Brunswick coast – Highway 11 – had been named the Acadian Trail. The rides were short but came as quickly as I desired them to, and the entire southeasterly route from the Québec border through New Brunswick was less than 400 kilometers. As I traveled I could make out Prince Edward Island, ten miles across the Northumberland Strait.

When I crossed into Nova Scotia, I picked up the Trans-Canada Highway again, heading due east and then crossing the narrow Strait of Canso separating Cape Breton Island from the rest of Nova Scotia. I picked up Highway 19, which took me along the northwestern side of the island. As the traffic thinned out and the little towns grew fewer and farther between, I slowed down, enthralled by the romance of the sea and landscape. Sheep grazed the high meadows of yellow clover and lavender, thickets of wild roses, huckleberries, raspberries, leading down to the fishing villages and plummeting into the Northumberland Strait.

A ride dropped me off midday in Margaree Harbour, a picturesque village at the mouth of the Margaree River. I walked around until I found the most popular café. Afterward, hiking across the bridge over the river and out of town, I burst into a spirited song of the road:

Hike a stiff easterly breeze

with a bellyful of fish chowder –

the trawler’s come home with the catch.

Fling yodels off the precipices,

echoing down through the dales.

String the Acadian fiddle, lads!

Blow ye winds on the bagpipes!

Near Chéticamp I entered Cape Breton Highlands National Park, 366 square miles of high plateau and rocky coastlines. No roads led into its heavily wooded interior, and the park contained a wealth of wildlife, including lynx, bobcat, moose, black bear, and coyote [2]. Following the Cabot Trail, the road circumnavigating the park, I pushed on to the Highlands, the cloud-hidden spruce, jackpine, and birch reaches through which the Chéticamp River cut a gorge.

Near MacKenzie Point, knowing that the route was about to turn east and inland along the northern boundary of the park, I stopped for the day. Because I hadn’t stocked up on enough provisions to allow for multi-day camping, and the handful of official park campgrounds offered only the most basic tent-camping amenities, I realized this might be the extent of my stay. I followed a short trail to an overlook, and then wandered off that trail for some tent-free camping. From my sojournal:

camp on high cliff overlooking

the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

beyond that Newfoundland,

the Grand Banks,

the North Atlantic.

scrub pine for wind protection,

moss to cushion the bedrock.

quarter moon gives way to

milky stream of stars

to glistening blue sunrise.

Cabot Trail along the northwestern coast of Cape Breton Island

The next morning, I scrounged up a couple of apples and a hunk of cheese from my rucksack and sliced it all up for a little breakfast plate. I’d been on the road for almost twenty days and hitchhiked over 2,000 miles to arrive at this beautiful morning in this spectacular place. And that was it. That was all I needed or wanted from this trip. From that point on, I was moving in the direction home – across to the eastern side of the island and then south along the coast. I was packing Gary Snyder’s Turtle Island in a pocket of my rucksack, reading and rereading his poems and essays. In “Four Changes,” I’d underlined: “Balance, harmony, humility, growth which is a mutual growth with Redwood and Quail; to be a good member of the great community of living creatures. True affluence in not needing anything.” After camping for the night on a beach, I wrote in my notebook:

driftwood and smooth beach stones

are ideal for campfire cooking.

boil brook water

add five hands

of rolled oats

stir until thick

mix in honey, raisins, sunflower seeds

rich helping of peanut butter.

this

will last until midafternoon.

After stepping off Cape Breton Island, I continued along the southeastern coast of Nova Scotia, small fishing ports anchored to the rugged coastline, interrupted by Halifax, the only substantial city in the province. The white horses of the surf raced along, the ocean tossing tangles of rigging and mislaid lobster traps on its shores. Big-boned gulls met up at the cannery docks after following the fishing trawlers home. Little fingers of the ocean curled up into the land, beckoning – Halifax Harbour, St. Margaret’s Bay. The land jutted out its chin where the storms broke and the wind never ceased – Fox Point, Western Head. Across the waves, a white-rocked beacon cast its lonely eye across the ocean, a mother searching for her son, lost, swept away.

I was traveling easily, unhurried, no schedule, no deadline, this time with myself. When I wanted a break from the road, the ocean was never far. Because of the Gulf Stream, the southeast coast of Nova Scotia offered bracing but pleasant waters for swimming:

still cove of rock

shelter from the sea’s turmoil.

cliffside coursing with pink granite

flecked with agate and quartz.

water transparent

twenty feet deep off this edge.

sea tern enters

circles

dives for its meal.

When I reached Yarmouth, at the southern end of Nova Scotia, I took my leave of the Maritimes. I booked passage on the ferry out of Yarmouth Sound, past the Cape Forchu lighthouse, across the Bay of Fundy as the evening fog rolled in – 180 kilometers to Bar Harbor, Maine. I roamed the ship, observing my fellow passengers, stopping at the bar for a Moosehead Ale and a shot of rye whisky. On the stern deck, I met two free-spirited women travelers from Minneapolis and kept their company for the rest of the voyage, sharing their cigarettes, drinking ales and conversing between blasts of the foghorn, falling in love with ballet-bodied, green-eyed Mary – but we kept it friendly. Listening for whale songs through the night, we disembarked at sunrise.

I had one stop to make on my way back home. After graduating from Iowa, my friend Tony Hoagland had moved to Ithaca to test the post-graduate waters of the writing program at Cornell. I took US Highway 2 through the backwoods of Maine and into New Hampshire. Early that afternoon, as I was passing through the White Mountains, ten miles north of Mount Washington, I came upon a cascading mountain stream beside the road. I asked the driver to pull over to let me out, and climbed the hillside, following the stream, until I came to a place where the water pooled beside large basking boulders out of sight of the road. I stripped down and floated in the cool, clear mountain water, high on the wonder of it all, thinking about Tony:

I reached up to draw

the pennyroyal from my ears.

Rushing back came the sound of water.

The river reclined on rock contours,

pocketfuls of coins laughing down its slope,

the sacred chords of silvery promises.

As I lingered, the sun dried thoughts of you on my skin.

One last border to fall before the flints of our souls will strike again.

I continued on Highway 2 into Vermont, then south on I-91 and west into New York State, reaching the Hudson River and Troy by nightfall. By then I was deep into this notion of an epic or mythic odyssey, and scribbled in my journal the next morning:

I’ve descended from the northern lights, where the stars streak with their weight to earth. There I watched the brazen criminal sun break through the granite chill. But last night I walked through the seven-storied ruins of Troy, and today I drift as sluggishly as dust across this valley. How will this compare with you – your movements swift and delicate, like the red fox?

I reached Ithaca that afternoon and spent a good couple days hanging out with Tony, talking about poets and poetry, getting high and swimming in Lake Cayuga. (Tony was always a great swimmer, and a member of that communion of saints.) Although as restless and footloose as I was, he was able to envision a life as a poet and teacher and work toward it. His focus was inspiring.

By the end of August I was back in Iowa City. Changes were in the works. My housemate Pat had given birth to a son, Sierra Soleil, in February. Like everyone in the house, I was helping raise him, but Pat and Sierra were moving to Santa Cruz to stay close to his father. I’d decided to not spend another winter living in the unheated attic of the Governor Street co-op house, and was about to move into the first-floor apartment of a house on Fairchild Street with Thomascyne, a feisty red-haired art student who would open doors and point me in new directions.

Footnotes

[1] When I was thirteen, I selected Anthony of Padua as my confirmation saint. I liked that he was the patron saint of lost causes, and that adding Anthony to my name made my initials D.E.A.D.

[2] In 2009, Taylor Mitchell, a young Canadian country singer, was attacked by coyotes on a trail near Chéticamp, and died from her wounds.