Going Down to Mexico, Part 6

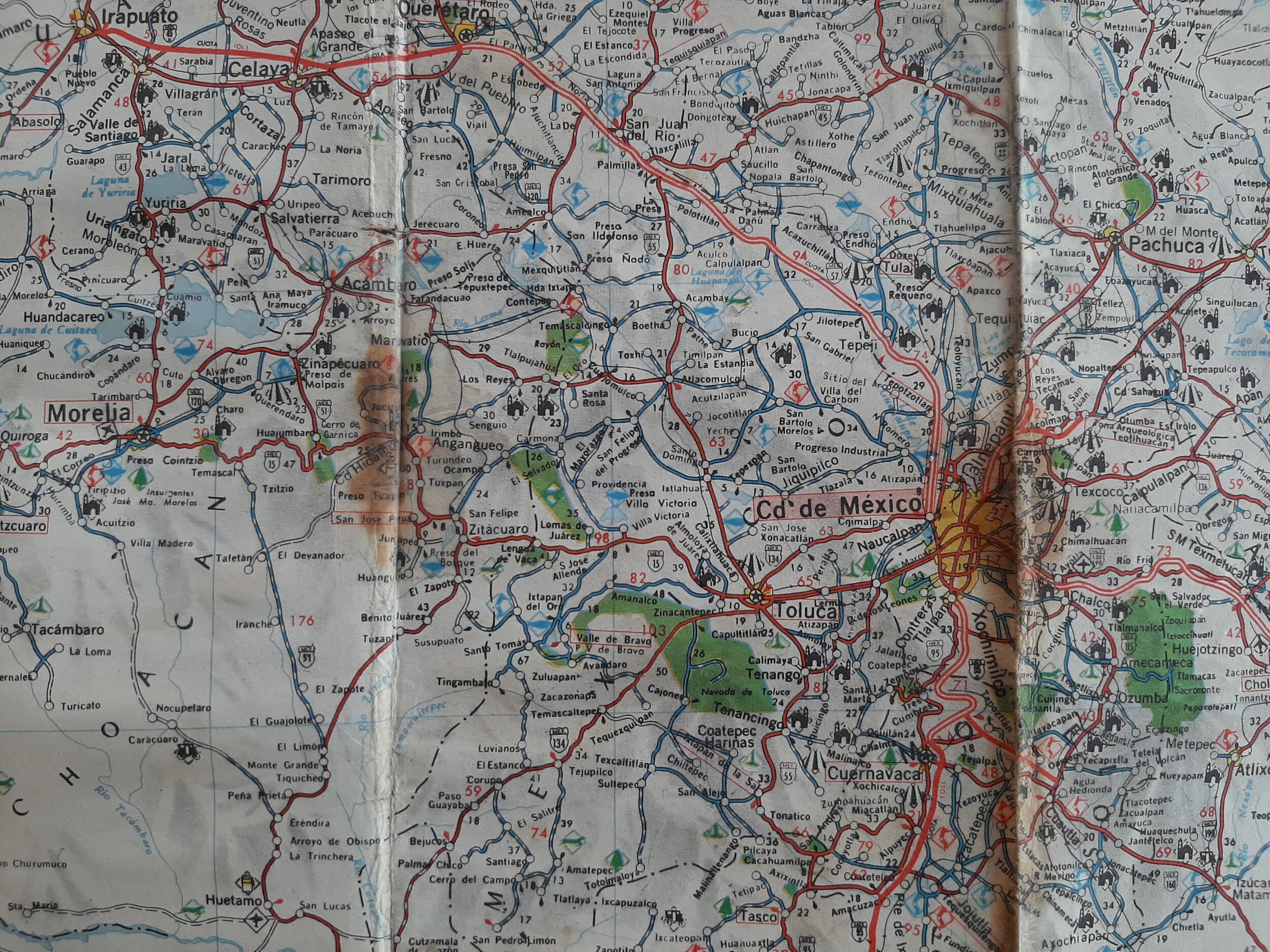

The route from Ciudad de México to Morelia represents the first 15% of the 2,100 kilometers I traveled in this last installment to return to the U.S. This is the trusty road map I used in 1976-77 and 1980, in the days before Google Maps.

“Really to see the sun rise or go down every day, so to relate ourselves to a universal fact, would preserve us sane forever.” –Thoreau

I left Ciudad de México and its twelve million inhabitants on February 22. Because of my backpack, I couldn’t take the Metro, but a confusing bus ride and some hiking eventually got me to Highway 15, the main road heading west. I quickly hitched a ride from three estudiantes taking a day off from book-learning and going to Toluca. They took me to the Calixtlahuaca ruins just north of the city, and we explored the stone pyramids for an hour before they dropped me off on the western edge of the city. Just as I was about to give up on hitching, two guys going to Guanajuato stopped, and we traveled through the late afternoon pine forest mountains. As we crossed into Michoacán and the sun was setting, I said, “¡Alto aqui!” and climbed a hillside into woods until I found a level spot and rigged up a shelter from the hail that came not long after.

I started hiking the next morning in the clear mountain air, but soon got a lift from a busdriver, and off we went to Zitácuaro, the bus filling along the way with indigenous Mazahuas, the women identifiable by their beautifully embroidered blouses and layered skirts. I bought bananas at the market and my favorite treat, calabaza dulce, from a street vendor and walked to the edge of town. A friendly couple soon stopped and took me fifty kilometers to Ciudad Hidalgo. Noticing a marker on my map for an agua termal, Los Azufres, I hiked five kilometers to the turnoff and then grabbed a bouncing twenty-kilometer ride in the back of a pickup up a logging road to a blue lake fed by a hot mineral spring. I set up camp on the far side of the lake and dove into the bone-chilling water. The first campfire I’d made in a while warded off the mountain night chill.

In the morning, I found the hot spring by following the rotten-egg smell of sulfur (azufre) to its source. A simple setup corralled the spring in a four-foot-deep pool, the overflow spilling into the lake, so one could comfortably steep in 90-degree water. I shared this delicious pleasure with one family, soaking for over two hours, luxuriating and exfoliating.

Next day, a couple of quick rides took me to Morelia, where I stopped for lunch and stocked up on fruit, veggies, and eggs, and then camped on its outskirts at the edge of a cornfield. In the morning, the first passing car stopped to pick me up, two young guys just returned from a year in Chicago. I decided to stop in Zamora for lunch, checking out the city and treating myself to their famous chongos zamoranos. Then three men en route to Guadalajara gave me a lift in the back of their pickup. As we passed along the southern shore of Lago Chapala in the late afternoon, I tapped on the top of the cab to stop, clambered out, and found a spot beside a stream at the edge of a strawberry field – laundry day at the lakeshore, sweet juicy fresas for breakfast (and lunch and dinner).

After a three-day break, I was back on the road, a couple of rides taking me to Guadalajara. I eventually wandered into a plaza where lots of handsome young kids were setting up a stage, so I stayed late to enjoy a ballet performance. I found a church and sought out the priest to ask for a place to sleep. He filled my need by taking me to the Civil Hospital Alcalde, where I slept in a spare bed in the men’s ward. In the morning a nurse placed a glass of milk on the bedside table like a votive candle.

I was now moving steadily, not in a rush but making miles most every day. I hitched a ride from a young couple and their two sons traveling from Mexico City to Puerto Vallarta. So, across Jalisco and into the dry rugged mountains of Nayarit until our paths diverged near Avakatlan. The next morning, a well-dressed elderly man stopped to give me a lift. He spoke good English, and I sensed this was an opportunity to share the message. He listened intently and then offered that he too was a seeker and had found his answer in Kirpal Singh, master of a spiritual practice known as Yoga of the Sound Current. We stopped in Tepic, the capital of Nayarit, and he treated me to brunch at the Hotel Junipero Serra, where I enjoyed enchiladas verdes on a veranda overlooking the city, my fanciest meal in Mexico. He was on his way to Culiacán but diverted from his route to visit the fishing port and surfing town of San Blas, and I tagged along. I thought about staying a few days but had a difficult night camping in a palm grove near the beach, where I was attacked by mosquitoes and sand fleas.

In the morning I moved on, a short hike and then a ride back to Highway 15, now heading northwest. Crossing the Río San Pedro, I decided to stop for a swim to wash off the heat, dust, and sand flea memories. I crossed the bridge and hiked upriver a kilometer, stripped down to my shorts and, in my excitement to cool off, dove from a six-foot bank into four feet of water. Luckily, the bottom was muddy, but it was a hell of a jolt that dazed me and left me stiff and sore for days – from my head and jaw down my spine. My mother always displayed on the wall by our dining room table a small framed picture of an attentive guardian angel hovering near a boy and girl at the edge of a cliff. Was that the spirit that saved me? I rested up and recovered for a day, visiting the nearby pueblo and catching a glimpse of some of the reclusive Huichol people who live in the nearby mountains.

The next day I caught a ride from a semi driver, a thoughtful hombre into writing and philosophy and Kahlil Gibran. We made a connection and I shared the message with him. He dropped me off on the outskirts of the tourist city of Mazatlán, where I wandered through quiet Sunday afternoon streets and down to a stone jetty away from the busy beach hustle to watch the waves break and the sun set on the ocean.

The land was becoming increasingly arid as I continued north. A ride into Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa and the pre-cartel Mexican drug business, a city with more flashy cars per capita than any other in Mexico. I stopped in a plaza for a lunch of fruit and chatted with a law student. A long walk to the outskirts of the city, a long wait, and finally a short hitch to a naranjal, where I camped that night under the fragrance of orange blossoms. After oranges for breakfast, I stuffed my backpack with a dozen more.

My second hitch of the day, from a friendly taxi driver and shrimper, took me to Los Mochis. He invited me to his home for comida (the main afternoon meal, as is Mexican custom) with his whole family – his wife making bread, son and pretty daughter-in-law, 84-year-old father-in-law, brother. Mucho platicando – lively discussion of life in Mexico versus Estados Unidos. Afterward, he dropped me off downtown. Two days of steady hitching took me another 650 kilometers north into Sonora. My last night in Mexico, I camped at a water reservoir on the outskirts of Hermosillo, celebrating by baking a banana-chocolate cake in a pan over my campfire coals. From my journal:

the dry places

the Sonoran Desert

the wind comes

slipping over the hills like a hawk

hot iguana sun and saguaro statues

in the stillness of the coyote darkness

a sky of glittering diamonds

spirits lose their power

At the end of over 4½ months in Mexico, I took a bus to the frontera, retracing the route of my brief excursion into Mexico two years earlier, the same blind boy playing harmonica for change outside a dusty bus stop diner. His playing had not improved. I crossed the border from Nogales, Sonora, to Nogales, Arizona, like going through some cultural time-warp, except we all were alike in so many more ways than we were different that the differences were insignificant.

I caught a lift from a Mexican American going to Tucson after visiting his dentist across the border. He also picked up Dean, a scruffy young hitchhiker from Indiana, and we headed north on I-19, him drinking tequila as the novacaine was wearing off. I volunteered to drive because he was weaving badly, but he turned me down. As we came up on two Arizona state patrol cars pulled off the shoulder to make a stop, I warned our driver to “maintain.” He did, by slowing down to twenty miles an hour, and still almost took off the driver side door of one of the patrol cars. We were nabbed a few miles down the road, or he was nabbed, drunk, with no car registration and a trunkload of suspicious mag wheels. Dean and I got our IDs checked and our rucksacks sniffed by drug dogs and told to walk to the next exit ramp.

When I got to Tucson, I called Iowa City, nervous with anticipation, and talked with Pat. It was a happy long-distance homecoming, tempered by the news that she had miscarried back in the winter. I was surprised how good it felt to talk with a friend, someone from my household, someone whom I’d worked beside many nights in the bakery. This, I realized, was my home (or home base), my family, all that made the journey meaningful. Pat was heading to California to visit family and friends, so we made plans to meet in Santa Clara in a week.

I took my time hitching up the coast. On the vernal equinox, I camped with a Dutch macrobiotic cook named Biek and another hitcher in a Big Sur meadow, waking at sunrise in a field of California poppies. Pat and I met up later that day, a sweet comfortable reunion. We hung out in Santa Cruz for a week and then hitched back to Iowa City. During those ten days together, our friendship deepened to something that would develop into the foundation for our marriage, four years later.

Back in Iowa City, I barely knew how to talk about this six-month journey. What happened to Michael, and all the others whose paths I crossed? I didn’t have a good answer to the question Dylan posed in the song he wrote when he was twenty-one years old: “Where have you been, my blue-eyed son?” Perhaps I’m only now beginning to “learn my song well.” My last journal entry ended:

April 1st we return to Iowa City / the end of a lot of miles / i’m here now and something’s going to happen but i know not what / wait to hear from Prch in Ann Arbor back from his travels / think about Naropa, the Rainbow Gathering, Cheryl in Vermont, other places or things to do here in Iowa City – the house, the garden, friends on nearby farms, poetry, Stone Soup, some job or another, connections getting rewired / i’m waiting

Glossary

chongos zamoranos - a sweetened milk curd dessert flavored with cinnamon

naranjal - orange grove