Balancing Act: Living (and Teaching) Through a Plague, Part 3

Wednesday, 25 March 2020

Just one day after the latest snow had melted, always a surprise, those ephemeral beauties – purple crocuses! – popped out of the ground.

Thursday, 26 March 2020

I cleared the garden yesterday, looking to see what might be sprouting this early spring. I pruned the wild raspberry canes that grow around the compost bin so I could access the hatch at the base of the bin. Then, I mined the rich vein of compost, using hand tools to reach as far and as carefully as I could, making sure the tunnel didn’t collapse. This labor yielded a wheelbarrow-load of dark humus littered with brown eggshell fragments, which I strewed over the garden. In the last few years, I’ve neglected to save my kitchen scraps for the compost – one less task to complicate my life – but I’ve vowed to reinstate that practice.

Saturday, 28 March 2020

Four women are walking down the middle of our quiet street and talking so loudly I can hear them from inside the house, their voices raised because they’re spaced five feet apart, in a neat square shape. As the coronavirus marches on, as the informal quarantine continues, everyday activities look and feel different. Walking through the City High parking lot, I saw three teens sitting on beanbags beside their cars, forming an equilateral triangle whose sides are six feet long, perhaps talking about geometry or sex or both. On Lower Muscatine Road, in the driveway next to their house, a brother and sister play a violin and cello duet.

Other than a trip to school on Monday morning, when the building was opened for anyone needing to pick up work or equipment, I’m staying close to home. Climbing the stairs to the second floor, I came upon five other teachers spread out in the hallway and lingered there, hungry for conversation and connection. On Wednesday afternoon, Adam started a group text for all the English language arts teachers. The thread went on for four hours as we shared favorite jokes and memes, photos of our pets and spouses. Missing each other, and human contact in general, we realized this is now what’s available to us.

At least once a day, I feel a little frisson of Covid-19, wondering if I’ve contracted it, and what I’ll need to do if I have. Yesterday evening I broke my quarantine by ordering from Wig & Pen, an old Friday tradition to celebrate the end of the workweek (except I’ve been doing little work). Cautiously walking into the shop to pick up one of their mozzarella-laden Flying Tomato pizzas, gingerly handing over my credit card, I feel the weight of my irresponsibility. When I think about what’s happening in Italy and Spain and New York City, I recognize the privilege of my ability to work from home. I want to show respect for my fellow human beings, and don’t want to contribute to the virus’s spread. Even though its impact on Iowa has been minimal, Johnson County is the state’s epicenter, home to over 25 percent of its cases.

I’d almost forgotten that this coming Monday is my wife’s birthday. But Pat’s still in my mind – always will be, I’m sure. Sixteen months after her death, I can still feel her presence – a breeze brushing my arm, a tingling sensation – then I remind myself she’s gone. Well, the thought of her is with me, but I can no longer read an interesting passage to her or rub her back or give her a hug. I often take an afternoon siesta in the red leather recliner, one of the few places where she could sit comfortably in her last year. More than once, I’ve awoken from a dream of her, certain she had been sitting right beside me. A friend has urged me to consider this not as a figment of my imagination, but Pat’s spirit paying a visit. Doing this has become a solace.

Working in the garden this week, I pay attention to the buds on flowers she planted – the orange-and-yellow flames of the early-blooming dwarf tulips, the forget-me-nots preparing to share their blue reminders. Scything down and raking out the waist-tall stalks from the patch of bee balm that grows by the creek, I’m enwrapped in and enrapt by its fragrance, its resilience, its minty balm. The sprouts of this year’s bee balm are emerging, but the flowers won’t bloom until mid-summer, a brilliant swath of scarlet in the back of the garden. Hummingbirds – and bees, of course – can’t get enough of them, their buzz and hum audible from a distance. According to the website Practical Self Reliance, “Bee balm is antimicrobial and soothing, so it’s often used to treat colds and flu.” The petals are not only used in medicinal teas but are also edible. I might try some on my salads this summer.

Tuesday, 31 March 2020

I’ve been thinking about our response to Covid-19, our efforts to open our hearts and stay in the moment. We’re into the third week of sheltering-in-place and social-distancing, with the likelihood that it will now continue through the entire month of April. Maintaining some kind of emotional balance is needed during this quarantine time. It’s important to stay in touch with what is happening in the world around us. A twelve-year-old Belgian girl and a thirteen-year-old British boy have become the youngest victims of the virus; the 4,000-member crew of the USS Theodore Roosevelt aircraft carrier are now in quarantine after an outbreak; a funeral in Albany, Georgia, has turned into a “super-spreader event.” And yet, following the news, we risk getting caught up in the potential dangers, the number of cases, the pandemic possibilities and what-ifs. That path leads to paranoia, an irrational fear of the world. A more constructive response is a rational fear of the virus.

I want to act responsibly – one way of staying in the present – washing my hands often, disinfecting surfaces regularly, avoiding physical contact as much as possible. I’m also trying to be aware of my habits or patterns of life. Although the district hasn’t yet given us guidelines on possible online learning, I’ve decided to start a daily email to my students, which has helped me focus. Each morning, I send a short message to each of my classes – AP Language & Composition, U.S. Humanities, and African American Humanities – letting them know I’m thinking about them, mentioning school work they might be doing, sharing a short reading and the song of the day. The last of these is a classroom tradition – to play a song during passing periods to get our minds dancing. It could be a new song I’m listening to – Sudan Archives’ “Nont for Sale” or Fiona Apple’s “Fast As You Can” – or a timely song such as Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” or The Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” (an obvious choice) or a joyful energetic number such as The B-52’s “Love Shack.” These daily emails impel me to keep my students in mind as I go through my day, reading books, listening to music or podcasts, watching movies – activities that keep my mind engaged with meaningful work.

Because the weather has been kind, I’ve been able to go for runs and walks, and work in the garden, clearing off the dead leaves and vegetation, getting the garden ready for planting. I visited my neighborhood garden center yesterday afternoon – again, feeling a bit uncomfortable about disregarding the informal restriction – to pick up vegetable and herb seeds, starter mix, topsoil, and a witch alder shrub to replace the burning bush I had cut down and excavated. I appreciate how this is helping me focus on productive solitary activities and staying in the current moment of spring and rebirth.

One silver lining of the pandemic is that I’m getting better at using online communication tools. I set up a Google Meet with Sierra, Emma, and Jesse this past Sunday. I have not been great at staying in touch with them, and decided this would be one way to bring us all together, to strengthen our Roanoke-Iowa City-Austin-Seattle ties. It worked fairly well, and everyone is on-board with doing this on a weekly basis. If I call on Sunday at 4:00 p.m., it will be five o’clock in Roanoke and two o’clock in Seattle. Yesterday, the Washington ELA department met on Zoom for an hour and a half. We had an agenda, which primarily justified our need to chat, catch up, enjoy each other’s company, offer moral support. These online meetings gave me some practice for the Google Hangouts editorial meeting I’ll be holding with my Washington Literary Press kids this afternoon.

Because I live alone now, the lack of physical contact has been a challenge. When I’m working in the yard, I wave to and converse with my neighbors, and I’ve noticed the increased friendliness of our little sidestreet. On walks with my friend Jennifer, we’ve engaged in comforting and affirming exchanges about how we’re learning to rebound from loss. I hope to reach out to other friends – Sharon and John, Mary and Steve, Nancy – to arrange conversational strolls with them.

I’ve definitely noticed some hindrances to staying present since the onset of the pandemic. Becoming anxious or overwhelmed by all the news could send anyone into a tailspin. Because of my physical isolation, I need to get better at staying on task and following a schedule. I sometimes flit from one thing to the next – a butterfly’s focus that doesn’t usually feel productive or satisfying. I don’t want to force myself into a rigid schedule, but I do want to say, “I’m going to read this afternoon,” and then do so for an hour or two without interrupting myself. The night is my most productive writing time, but I was up until four a.m. last night, and those were not productive hours. I don’t want to always be nose-to-the-grindstone, but I do want to be engaged in work, by which I mean “activity involving mental or physical effort done in order to achieve a purpose or result.”

Friday, 3 April 2020

We seek out the small signs that we’re still human and whole and hale.

In our Zoom meeting

The birds are singing at Alexia’s home.

She’s sharing her home with us.

We share our homes with each other.

This is how we will learn to love again

After the pandemic.

Balancing Act: Living (and Teaching) Through a Plague, Part 2

The new maroon Converse All-Stars of joy.

Monday, 16 March 2020

The Covid-19 pandemic (and the public response to it) is getting more and more serious. School has been canceled for four weeks – spring break and the following three weeks of scheduled school. Are we going to extend our school year by three weeks? But it’s all for the best. Even though it has barely infected our little inland state, the virus is wreaking widespread and deadly havoc in other parts of the world, and this could potentially go wild everywhere. Shutting everything down is the smartest thing to do to minimize the spread of the virus.

Nonetheless, I’m feeling the disappointments of canceled events I was involved in organizing – no student-staff basketball fundraiser match-up, no Just Mercy movie field trip and Black Writer guest speakers for my African American Humanities classes, probably no Chicago field trip for my U.S. Humanities students (scheduled for April 28), maybe no Guatemala student service trip (scheduled for June 1-10). I’m trying to resist the impulse to wallow in my anxiety that the rest of the school year will be canceled. The Flu Pandemic of 1918-1919 infected over 25 percent of the world’s population and killed approximately 50 million people. You might think we are more knowledgeable and better prepared a century later, but we don’t seem to be. Our nation’s slow response, in terms of canceling events and gatherings and putting together testing kits, even as the virus was hitting China like a sledgehammer, suggests that this will get much much worse.

Last Wednesday, we were able to squeeze in our African American Humanities field trip to Hancher Auditorium just before everything started shutting down. The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater performance was amazing. A friend of mine in the marketing department may have played a role in reserving the front row center seats for us. Twenty minutes before the performance began, many of the dancers were on stage warming up, giving us a fascinating peek behind the scenes. The performance combined historical background about Alvin Ailey and the dance troupe with two dance pieces, which included some participatory dancing in our seats. My students loved the experience, and yet, I will feel terrible if any of them contract Covid-19 because they came into contact with the virus at the show.

In the front four rows of Hancher Auditorium, my students and their chaperones await the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater performance.

Saturday night, my friend Jennifer and I watched a stunningly beautiful movie, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, at Film Scene, a day before it closed its doors. The twenty people in the theater all carefully chose “socially distant” seats, but one might argue we were being unnecessarily risky. And last night, six friends came over for what had been planned as a potluck dinner to welcome my daughter Emma and her two sons. Although Emma had to cancel their trip, it felt good to get together with friends and enjoy some delicious food. We cautiously bumped elbows rather than hugged, and our gathering was well under fifty people, so we obeyed that restriction, but again I wonder if we were being foolhardy. I’ve made a list of errands and tasks I don’t have time to do when school is in session, but out of sympathy for store clerks and cashiers, I’m hesitant to enter shops unless I must.

Tuesday, 17 March 2020

I had a Covid-19 nightmare last night. People with the coronavirus were taking everyone else with them. Once they knew they had the virus, they gathered everyone with whom they had been in contact into a room and then shot them all and then shot themselves. I think this has something to do with the fact that people have not only been stocking up on toilet paper and antiseptic wipes and hand sanitizer but also guns. Why do people feel that they need more guns and ammunition at a time like this?

Thursday, 19 March 2020

Inspired by Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights and determined to cling to some optimism during these dark times, I’m attempting an essay on the joy of pancakes: When my kids were young, I would usually make pancakes on Saturday morning. When Pat was working on her nursing degree, taking classes during the day and working evening shifts at the nursing home, I would sometimes make pancakes for dinner. (The kids made fun of me because they claimed I only knew how to make flat meals – homemade pizzas, pancakes, tacos.) Somewhere along the way, I found a good pancake mix recipe: unbleached white flour, whole wheat flour, cornmeal, a bit of buckwheat or seven-grain flour, baking powder, baking soda, salt. I’d often add blueberries or overripe bananas, and in the summer, leftover sweet corn off the cob. Sometimes I’d make small silver dollar pancakes. The kids liked this tradition. As they slathered the pancakes in butter and syrup and peanut butter, they’d often sing, “she never made me pancakes,” which I somehow assumed was an Ol’ Dirty Bastard song, but it turns out it’s from the song “Pancakes, off The Legendary Marvin Pontiac: Greatest Hits album.[1]

Now I make those pancakes for my grandsons. They have come to expect them whenever I visit them. They call them Poppy Pancakes and claim they’re the best. As I cooked some on the griddle this morning, I meditated on the transformation from batter to pancake by the influence of heat, how the batter slowly rises on the griddle, bubbles forming on the surface and then popping, the edges lightly browning, a signal the pancake is ready to be flipped. A sweet and simple way to show my love for my children and my children’s children.

Monday, 23 March 2020

Spring break is over and we should be back in school now, but we’re not, and won’t be for at least another three weeks, probably longer. It’s distinctly possible this school year will be canceled entirely. I worry about my students. Are they safe and sound? Are they following pandemic restrictions? Are they bored? I sent out an email to all my students today just to connect with them, a habit I plan to continue until we are together again.

The snow that fell yesterday outlines the branches of every tree and bush, the sharp contrast of black and white, but the snow is already melting and dropping from the trees as I write.

On a whim and out of a desire to give myself something to look forward to, I’d ordered a pair of maroon hightop Converse All-Stars on Amazon. Rather, the fifteen-year-old inside of me ordered them. And the fifty-year-old didn’t complain or object, nor did the sixty-five-year-old who is the combination of the other two. These were the tennis shoes I wore all through my teen years. They were the basketball shoe de rigueur at that time – lightweight canvas uppers, high tops whose extra support protected against ankle rolls, rubber soles in a grid pattern that enabled us to make sharp cuts on the hardcourt. We called them Connies or All-Stars, never Chuck Taylors or Chucks. That all came later.

Only two colors were available back in the sixties – white and black – and I always wore white Connies. Now, Chucks are fashionable casual wear rather than athletic shoes, and come in a rainbow of colors. When my maroon hightops arrived on Friday, I immediately laced them up. In a time of coronavirus and sheltering in place, they make my feet feel lighthearted and fancy-free.

Tuesday. 24 March 2020

I love moments when minds intersect, when paths cross, and I get to witness those serendipitous moments. Here’s a “conversation” that took place yesterday between a scientist (Hope Jahren’s memoir Lab Girl) and a poet (Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights) about the symbiotic relationship between fungi and trees. While reading Jahren, I came upon this:

Every toadstool, from the deliciously edible to the deathly poisonous, is merely a sex organ that is attached to something more whole, complex, and hidden. Underneath every mushroom is a web of stringy hyphae that may extend for kilometers, wrapping around countless clumps of soil and holding the landscape together. The ephemeral mushroom appears briefly above the surface while the webbing that anchors it lives for years within a darker and richer world. A very small minority of these fungi – just five thousand species – have strategically entered into a deep and enduring truce with plants. They cast their stringy webbing around and through the roots of trees, sharing the burden of drawing water into the trunk. They also mine the soil for rare metals, such as manganese, copper, and phosphorus, and then present them to the tree as precious gifts of the magi.

Jahren goes on to ask why they are together, but posits no scientific answer, only suggesting that “perhaps the fungus can somehow sense that when it is part of a symbiosis, it is also not alone.” Maybe she’s guilty of anthropomorphizing the fungi. Or maybe she’s suggesting lessons that we can learn from trees and fungi, reminders of what Paradise might feel like. In my reading last night, Gay continued this conversation:

In healthy forests, which we might imagine to exist mostly above ground, and be wrong in our imagining, given as the bulk of the tree, the roots, are reaching through the earth below, there exists a constant communication between those roots and mycelium, where often the ill or weak or stressed are supported by the strong and surplused.

By which I mean a tree over there needs nitrogen, and a nearby tree has extra, so the hyphae (so close to hyphen, the handshake of the punctuation world), the fungal ambulances, ferry it over. Constantly. This tree to that. That to this. And that in a tablespoon of rich fungal duff (a delight: the phrase fungal duff, meaning a healthy forest soil, swirling with the living the dead make) are miles and miles of hyphae, handshakes, who get a little sugar for their work.

Gay is a bit more explicit than Jahren about the allegory: “Joy is the mostly invisible, the underground union between us, you and me, which is, among other things, the great fact of our life and the lives of everyone and thing we love.” I’m sure Jahren and Gay are not the only two folks who have made these connections, but that I encountered this profound idea twice in one day is, well, pretty cool.

Footnote:

[1] Marvin Pontiac is a fictional musician created by the musician, painter, actor, and director John Lurie.

Balancing Act: Living (an Teaching) Through a Plague, Part 1

The self-serve coffee bar in my classroom at Washington High School. The decorated mugs were a gift from one of the Washington Literary Press staffs.

Tuesday, 11 February 2020

Last Friday, my decision to retire from teaching went public (on the Cedar Rapids school board agenda). I had already talked with my department chair, Adam, about this, and learned he was in the process of requesting a one-year leave of absence. After school on Thursday, I spoke with Julie, one of our instructional coaches and a close friend. Those conversations reminded me how bittersweet this decision is. I count Adam and Julie as two of my closest colleagues. As is true of so many of the teachers I’ve gotten to know over the last fifteen years, I have tremendous respect and admiration for them. I’ve witnessed teacher after teacher draw upon a seemingly bottomless well of empathy and compassion in order to connect with and support their students.

During my prep period on Thursday, I also stopped by to share my retirement plans with John, our principal. The conversation was as strange as many of our conversations have been. He asked if there was anything he could have done to keep me here, offering me an opening I gently stepped into. Already sixty-five years old, I had planned to teach one more year at most, but yes, his inability to address the everyday needs of his staff played a role in my decision. If he didn’t know that already, he’s even less astute than I had thought he was. At one point, he reminded me that his “laser focus” has been on helping our students to be academically successful. I reminded him that if that focus on students means that he ignores and fails to support his staff, to the point where their low morale affects their work in the classroom or persuades them to leave the profession, well, then he’s a pretty lousy principal. I don’t know if he heard what I had to say, or heard it but is incapable of changing himself.

Adam and I shared our news with the rest of the English department on Monday during lunch. After school, six of us gathered in the hallway and talked through our feelings. I’m trying to offer my colleagues some perspective: even though the two of us are veteran members of the department, they’ll forge on without us. If the school is able to hire someone like Tiphany, a first-year teacher who has been doing amazing work with her LA 10 classes and the Journalism program, they’ll be fine. After I went public with my retirement plans, during separate conversations with John, Julie, and Tiphany, their eyes welled up with tears. This surprised me. I don’t consider myself specially kind or thoughtful, but that reaction tells me I’ve had more of an impact on them than I might suppose.

Thursday, 13 February 2020

For teachers, snow days can be a gift. Yes, I’m annoyed that everything I wanted to do with my students today won’t happen, and my week’s lesson plans have been thrown into disarray. But I can let go of that. I’ve been reading Steven Levine’s book A Year to Live. A poet and teacher working in Buddhist traditions, Levine offers readers guidance in “how to live this year as if it were your last.” This snow day has allowed me to work on what he describes as a Life Review. I’ve started this chapter a couple times but keep setting the book aside. It’s a challenging and difficult step in the process. As I read the chapter, my mind dredged up memories, most of them weighed down by regret.

Levine eases us into this tough work, advising us to start with gratitude. My seventh-hour class knows they can get me off-track by nudging me to tell stories of my youthful adventures, hitchhiking stories about the kindness of strangers who helped me land on my feet when I was tripped up by adversity or my own foolishness. Levine then says we should turn to painful memories and offer forgiveness to those who’ve done us harm. For me, this is a fairly short list. Yes, I’ve experienced small offenses, but few that I’ve nursed over the years. One that stands out is the mistreatment I endured from my neighborhood pal Mark H. That I remember his name says something, since I haven’t seen him since high school, and we stopped hanging out by fifth or sixth grade. He would exploit my trust in order to make me an easier target for his verbal and physical bullying. As I write this, I imagine running into him some day and revealing this harm I’ve harbored. And in that imagined moment, he apologizes, admitting his youthful failings. Levine writes, “Forgiveness finishes unfinished business.”

The last step of the Life Review is the hardest – the litany of regrets. The Brett Kavanaugh hearings this past year caused me to look hard in the mirror. Ten years younger than me, he too attended an all-boys Jesuit college-prep high school. His breezy abuse of women (alleged, but I have no doubt) led me to recall how we talked about and treated women then. As Levine writes, “I discovered a youth full of distrust, self-centered gratification, and emotional dishonesty.” While a girlfriend and I waited in traffic after a concert at Blossom Music Center, my inebriation and blind lust led me to make advances despite her repeated requests that I stop. Something kept me from doing the worst, but the next morning, I was steeped in shame. And yet, I never apologized to her. When a girlfriend from Ohio University came to visit me in Kentucky, I was cold and rude, perhaps because I feared her visit signaled a level of commitment I wasn’t ready for, but that’s all bullshit. I never explained my feelings to her, in part because I barely understood them myself. I’ve searched the internet for her, wondering what she’s doing now, wishing I could reach out and apologize.

I wasn’t always the best father, particularly when the kids were young. I inherited my father’s impatience and anger, aspects of him I abhorred. Levine reminds us, “There are moments in the life review for all of us when the going gets so tough we have to keep remembering to come back to the heart the way a mountain climber returns to an oxygen mask.” In recent years, I’ve apologized to my kids. Their nonchalant responses indicated either their readiness to forgive me or the insignificance of those incidents.

Over the forty-five years that I knew Pat, I hurt her many times, but she was good at calling me on it and not letting me off the hook. Out of necessity, I learned to own my mistakes and apologize, to wait in the doghouse for however long was needed until she was ready to forgive me. And I became a better man because of those apologies. Levine writes, “It really isn’t the act of contrition that sets the mind at rest but the intention not to repeat actions that cause harm.” I’m grateful that over the last ten years of her life, from her first open-heart surgery to the final two years of her cancer, I was perhaps the best partner I ever was.

Levine quotes the Hindu epic Ramayana as a way to describe the Life Review: “It’s like something I dreamed once, long ago, far away.” This brought to mind the Grateful Dead song “Box of Rain” and Robert Hunter’s lyrics: “It’s all a dream we dreamed/ One afternoon long ago.” As I listened to the song and sang along with Jerry Garcia, I was ambushed by a powerful blend of regret, forgiveness, and joy, and my eyes welled up with tears. “Maybe you’re tired and broken/ Your tongue is twisted with words half spoken/ And thoughts unclear/ What do you want me to do/ To do for you to see you through/ A box of rain will ease the pain/ And love will see you through.”

Saturday, 22 February 2020

There are raccoons in my attic. I’ve been hearing them most of the winter, frequently insisting to myself I need to go up there and ask them to leave. But then I’d forget about that task until the next time I heard them pitter-pattering around. The only official access point is a hatch in the garage ceiling, although I’m guessing the raccoons have gained entry through a rotten board in the eaves I’ve been intending to replace. I envision a showdown. The raccoons are surely nesting, if they haven’t already given birth to a little brood. It’s not easy to be nimble up there because there’s no flooring. I wonder if this is a metaphor for something in terms of my Life Review. Are there memories scratching around in my head I’m not addressing? It can be awfully easy to be untruthful with myself, to admit the easy truths in order to conceal the darker ones.

I climbed up into the attic, expecting to find a raccoon family unwilling to be evicted from their home. Yelling out as I crawled over the rafter beams, hoping to scare off the animals, I discovered no critters. Sometimes, harboring fear or anxiety is worse than facing dark truths. I replaced the rotten board in the eaves, hoping to discourage future uninvited boarders.

Later, I went for a long run. Running is one of my favorite meditative practices. I become conscious of the cadence of my breathing, the alignment of my spine, my hips swiveling, my arms pumping, my hands relaxed in loose fists, my feet hitting the pavement, heel to toe. Sweat drips from my eyebrows, even in 50-degree weather. Eventually I find a rhythm and stop thinking about my body and go into my head. Afterwards my skin tingles. That sense of well-being lingers for hours.

Saturday, 1 March 2020

A beautiful first day of March. While folks stroll together or walk their dogs or bike the trail that connects Court Hill and McPherson parks or play basketball on the new court at McPherson Park, I take a midafternoon run. We know more winter lies ahead, but we want to revel in the warmth while it’s here.

I’ve been reading Joan Didion’s essays. In “Self-Respect,” from Slouching Towards Bethlehem, she writes: “To have that sense of one’s intrinsic worth which constitutes self-respect is potentially to have everything: the ability to discriminate, to love and to remain indifferent. To lack it is to be locked within oneself, paradoxically incapable of either love or indifference.”

Saturday, 14 March 2020

Spring break in a time of pandemic. I’m trying to obey the quarantine, practicing “social distancing.” I just filled the bird feeders, and now I’m watching the nuthatches and chickadees and juncos and purple finches stopping by for snacks. I’ve been reading (and loving) Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights, an entry or two each night at bedtime. I admire the book’s concept – a year-long commitment to write a daily essay praising and embracing some small wonder – and I’m charmed by his digressions and veerings. Last night, his “Joy Is Such a Human Madness” piece resonated with me. (The title is a quote from Zadie Smith’s essay “Joy.”) Gay is drawing a distinction and a connection between pleasure and joy (or delight). He proposes that joy is “being of and without at once.” Working from Smith’s essay, Gay offers this conundrum: “The intolerable makes life worthwhile.” Gay goes on to describe the joy of parenting as “terror and delight sitting next to each other, their feet dangling off the side of the bridge, very high up.” That is, we can’t truly experience joy without having experienced some profound sorrow – suffering or loss or pain or misery. It is the contrast that transforms a pleasurable moment into one of true joy.

I’ve been more aware of this feeling lately. I cultivate it and nurture it. I think it could carry me through most hard times. At school, during these dark days of struggling with the obstacles laid down by an ineffective principal, I’ve tried to spread joy among the students and my fellow teachers. Although High-Five Friday has been temporarily canceled because of the Covid-19 threat, I love joining other teachers at the school entrances to greet our kids and wish them a good day.

Sixteen months ago, my wife, Pat, died. I wonder if this explains my increased awareness of these moments. Losing her, that continued loss, the empty place that had been filled for almost forty years, makes me grateful for all the sweet moments that feel that much sweeter. I’m listening to Joni Mitchell’s album Blue. In the title song, she sings, “Everybody’s saying that hell’s the hippest way to go/ Well I don’t think so,/ But I’m gonna take a look around it though.” Would the joy of paradise mean as much to us without the dark alternative of hell?

Cambiando Futuros en Guatemala[1]

Our crew before heading out on our first day of work.

It was the last day of our service project – to build a home for (and with) a Guatemalan family – but I don’t think any of us were ready for it to end. That morning we were working on the final touches – Byron and Manuel, our two Guatemalan crew leaders, our jefes; the student crew of Miles, Josie, Maddie, and Azul; and Ofni, the young father of the family who would soon move into this house. We installed two sliding glass windows and a solid-core wood door, and grouted the beautiful terracotta floor tiles that had been laid the day before.

Meanwhile, Ofni’s mother-in-law was making lunch on the stove we had installed. A pot of rice and finely diced vegetables was simmering on one burner, while tomates, chiles, and sliced cebollas were roasting on another. In short breaks between tasks, I kept an eye on the progress as she blended the roasted vegetables with cilantro, parsley, and toasted pepitas and sesame seeds to produce a sauce in which chicken pieces would be stewed. As a midday rainstorm moved in, we covered the tools and hauled a makeshift wood plank table into the house. Serenaded by the gentle staccato patter of rain on the sheet metal roof, the ten of us – our work crew plus Ofni, Maria, and their three-month-old baby Arleth Verenice – sat down to a delicious hot lunch of pepián de pollo, a traditional Guatemalan Mayan dish. We ate and smiled and laughed together, dry and comfortable in the warmth of good company.

Lunch in the new home of Ofni, Maria, and their baby daughter.

For the past ten years, my friend and colleague James Burke, a Spanish teacher at Washington High School, has been leading spring break service trips to Antigua, Guatemala. I’ve always been interested in this project, drawn by both my memories of a week spent in Antigua some forty years ago, and the enthusiastically positive demeanor of the students when they returned. James and I had been discussing the possibility of me joining a trip, but I couldn’t commit because of my wife’s health. In the fall of 2019, a year after she passed away, I was finally ready to do so, only to have the Covid pandemic shut down the trip just as we were getting ready to go.

James and I stayed in touch after I retired from Washington in June 2020, and when he told me this past October that a new trip was being organized, I enthusiastically said, “Count me in!” So, in the early hours of Sunday, March 12, I met three other adults and thirteen students at the Eastern Iowa Airport to fly to Guatemala City. By three in the afternoon, we were being greeted at the Aeropuerto Internacional La Aurora by Alexis, Eddie, and Gregorio, the three full-time staff of ImagininGuatemala (IG), the local NGO we’d be working with. We clambered into a 20-seater charter bus, navigated the Guatemala City traffic, stopped for dinner at Pollo Campero, and then headed on through the city and over steep mountains to Antigua, forty kilometers and two hours away. Antigua has all the charm that Guatemala City lacks. The city of 50,000 is a UNESCO World Heritage Site – cobblestone streets and narrow sidewalks border the brightly painted stucco walls of homes and businesses. We were dropped off next to a basketball court in Colonia Candelaria, on the northeast edge of the city, near the crumbling ruins of a church destroyed in the Santa Marta earthquakes in 1773.[2]

We fanned out to our nearby host families. James, Ceci Cornejo (a young paraeducator recently hired at Washington), and I stayed with Dina Cazali, a warm, generous woman who operates a small pension out of her home. Five private rooms open onto a second-floor walkway overlooking a central room on the first floor, all of which is under roof. The second floor reaches out to form a rooftop balcony filled with potted plants and clotheslines. My two companions are far more bilingual than I, but as we chatted with Dina, I realized she thoughtfully adjusts her speech to the needs of her guests, and I was able to easily follow the conversation.

After an orientation meeting that evening at the IG offices, we returned to our lodgings. On this Third Sunday of Lent, some of the churches were holding processionals. We could hear music in the distance, mostly horns and drums, somehow sounding both festive and mournful. As I walked up the hill, I passed un viejo, hunched over, maybe five feet tall. “Buenas noches,” I offered. He replied in kind, warmly, enthusiastically. Even to the many gringos who intrude upon their city, los Antigüeños son muy amable.

On Monday we were given time to get familiar with the city and its culture. I awoke at dawn to the sound of great-tailed grackles speaking a language different from the one birds speak in Iowa. A tinny church bell was struck, over and over, in no particular pattern, perhaps the repetition making up for the lack of resonance. We spent the morning on a guided walking tour of the city, starting with a hike up nearby Cerro de La Cruz, from whose heights we could admire a vista of the entire city and the ominous Volcán de Agua on its far side, and ending at the beautiful baroque facade of the Iglesia de La Merced, gleaming gold and white in the sun. That afternoon we traveled to nearby San Antonio Aguas Calientes, a Kaqchikel Maya town known for its traditional textiles, where we met the family of IG staffer Eddie and watched his wife demonstrate weaving on a backstrap loom. We bought textile items she and her neighbors had woven and then helped make (and eat) tortillas negras cooked on a portable comal.

View of Antigua and Volcán de Agua from Cerro de la Cruz.

We began our service project on Tuesday. We had been split up into three crews, each one led by two local housebuilders. The goal of each crew was to build a home for a family in need of better housing.[3] We loaded a large water cooler and our lunches into the back of a camioneta, and then clambered aboard, sitting on the sidewalls of its bed, arms wrapped around its rack, and traveled through the city of work. The house site was ten kilometers away on the edge of San Antonio Aguas Calientes. After meeting Ofni, Maria, Arleth, and Maria’s mother and sisters, who lived nearby, we lugged the toolboxes and the first six 50-kilo bags of cement from their porch and got to work.

Byron and Manual gave us instructions in Spanish. Thankfully we had studied our housebuilder vocabulary. Hammer is martillo, nails are clavos, pintura is paint, and the four-by-eight fiberboard sheets are láminas. When Byron said, “Quarenta bloques!” we knew how many cinder blocks to carry from a nearby stack to the 12-by-16-foot trench that was the footprint of the main room. Meanwhile, some of us wheelbarrowed sand to a packed dirt area between the outdoor sink and shower and the chicken coop, under the shade of a carob tree. After shoveling the sand and cement until it was well blended, water was added, and then more shoveling and mixing until it was the proper consistency for mortar. The walls went up, seven courses in front, eight courses in the back, with the second and last courses laid upside down so the cinder blocks could be filled with rebar and mortar for greater stability, and large bolts could be inserted in the wet mortar of the top course. Ofni worked alongside us, always a smile on his face. “David!” he would call out to me, just for fun. Maria, carrying sleeping Arleth in a sling tied over her shoulder, brought us a mid-morning snack – a bowl of freshly sliced pineapple.

On the ride back to Antigua that afternoon, I looked around at our student crew and thought about how much I was enjoying getting to know them, seeing parts of them they usually don’t share with their classroom teachers. Miles and Josie were excitedly comparing their lists of top ten breakup songs. Maddie and Azul called out to dogs lounging beside the road, to dogs assembled on a street corner by the mercado, seemingly living in their own worlds. As we rumbled through the streets of Antigua, we felt exhausted but happy, and somehow changed. We had proved ourselves in the crucible of a hard day’s labor. We smiled and shook our heads at the U.S. tourists wandering around in short pants and skimpy tops, oblivious to or in glaring opposition to the culture of the Guatemalan people.

Our second workday was just as challenging. I noticed that Ofni had carefully tied up some of the low branches of the carob tree. Our heads had been bumping into the large green bean pods as we worked on Tuesday. As we prepared to begin our work, I stopped to look up at the surrounding mountains, where carefully tended campos clung to even the steepest slopes, and directly overhead, where the pale wisp of a crescent moon was dissolving in the morning sun. We cut all the four-by-fours and two-by-fours that would frame the house, and drilled holes for the bottom plates of those walls. We prepared to pour the floor, again mixing the cement by hand – trece carretas de arena spread out ten inches thick, seis sacos de cemento poured over that, and for a top layer, siete carretas de piedrin.[4] We sifted and mixed the dry ingredients by shoveling them into a peak, como un volcán, then shoveling the entire volcano five feet away, then shoveling it back to its original location. We leveled out its peak and created a depression in the middle, adding water, mas agua, mas agua, como un lago, then formed an irrigation ditch around the lake, letting the water soak in until it was ready to be mixed into concrete.

Our mid-morning snack was a bowlful of sliced papaya. Ah, the taste of a fresh, tree-ripened papaya – the fruit all but melted in our mouths. And there was enough left for a dessert to go with our lunch of sandwiches and chips. Byron was ready to get to it after lunch. Maddie, Josie, Azul, and I formed a bucket brigade from the wet concrete into the house, while Manuel and Miles rapidly filled our three-gallon buckets with wet concrete. As soon as we supplied Byron, he emptied each bucket and troweled the concrete to a smooth level surface. When the interior room was done, we poured a six-by-twelve-foot slab adjoining the house for the outdoor kitchen. We were able to knock off at three o’clock, just as a light rain began to fall.

At the end of day two, with Maria’s mother and nephew Mateo in this photo.

On our third day the workload began to ease up. We framed the rest of the house, nailing the wall studs and top plate and rafter beams, adding frames for the windows and door. We tacked down the sturdy fiberboard láminas we had painted a bright turquoise color, cutting out space for the windows. Ofni brought us 16-ounce glass bottles of Coca-Cola, which we decided to store in the water cooler so they’d be ice-cold at lunchtime. Maria’s mother made us a lunch of spaghetti with vegetables, a kind of pasta primavera. And for an afternoon snack, Maria brought us a Guatemalan treat, rellenitos de plátano – mashed plantains stuffed with sweet frijoles, deep-fried and rolled in sugar. We worked until five o’clock, laying the twelve-by-twelve-inch floor tiles and installing the high-efficiency wood-burning Chispa cookstove.[5]

Friday was our last day at the house. After that wonderful lunch with the family, we wired the house for electricity, putting in three overhead lights and three outlets, and installed a plaque beside the door that announced the owners of the home and our role in constructing it. We gathered inside the house for a formal handing over of the keys. Byron gave a little speech, and Ofni expressed his heartfelt thanks, with bilingual Azul translating so we’d know all that was said. She didn’t need to translate the part when he told us we were now their lifelong friends, and were welcome in their home any time we wanted to visit. When we gave the house keys to Ofni, Maria, and Arleth, there were few dry eyes.[6] I was moved by the gratitude of the family, but also impressed by the students, who are struggling to shape their identity in a world fraught with social media, who at a tender age weathered a pandemic, with its social distancing and sheltering in place. They were fully in the moment. They understood the part they had played in this extraordinary kindness, this most human of acts.

That morning as we were loading up the camionetas, a man who lived next door was standing in his doorway watching us. He said something to the drivers I didn’t catch. Azul smiled as she turned to me, translating, “He said, ‘Take good care of those gems.’”

Footnotes:

[1] Cambiando Futuros (Changing Futures) is a slogan used by ImagininGuatemala, the charitable organization we worked with. I encourage you to visit their website and click on “how you can help.”

[2] After those earthquakes, the capital of the Spanish Kingdom of Guatemala was moved to present-day Guatemala City. The city that was eventually rebuilt became Antigua (as in Old Guatemala).

[3] Ours would be houses #181-183 built by the ImagininGuatemala NGO.

[4] Our concrete formula was 13 wheelbarrows of sand, 6 bags of cement, and 7 wheelbarrows of gravel.

[5] See this website for more information: Chispa Stoves / Clean Cooking Alliance.

Fatherhood & Sonhood

In 1995, at my sister Julie’s wedding - Dad, me, Uncle Dick (Dad’s only sibling).

“How can I try to explain?/ When I do he turns away again/ It’s always been the same/ Same old story/ From the moment I could talk/ I was ordered to listen” –Cat Stevens, “Father and Son”

As is true for many, my relationship with my father was complicated. Starting when I was a high school freshman in 1968, he and I would argue over the path our country was taking. Usually stirred up during dinner, these arguments often became quite heated. The MyLai massacre, anti-war protests on campuses and civil rights protests in cities, the cultural revolution of Woodstock and the Summer of Love, feminism and the Equal Rights Amendment, gay rights and the Stonewall demonstrations, Chicago police cracking protestors’ heads at the Democratic National Convention, National Guard shooting students at Jackson State and nearby Kent State. All these became the bases for our generational clashes of opinions, him defending the status quo, me demanding change.

Although neither of us ever admitted it, we were stimulated by this long-drawn-out contest of wills. At the same time, we disliked each other for what we became when we argued – obstinate, relentless, self-centered. One of the rules of our supper table was that we had to ask to be excused. I now want to take a moment to apologize to my nine siblings. Unable to get a word in edgewise, they were often forced to bear witness to these protracted altercations fueled by our mutual stubbornness.

One of the first poems I wrote in high school, later published in a pamphlet by Brother Al Behm, a Glenmary friend.

Of course, life with my father wasn’t all contention. In particular, I admired his ability to enjoy his life. I have in mind a picture of him dancing with my youngest sister, Christina, at her wedding reception. It was the last summer before his death. Battling liver cancer and undergoing chemotherapy treatments, he somehow looked robust and vigorous in his tuxedo. Fully in the moment as he guided his daughter around the spotlight of the dance floor, he had a style distilled from the simple pleasure of living in this world.

John David Duer was born in Akron, Ohio, in 1924. His father, Johann Baptiste Duer, had immigrated from Hard, a small Austrian fishing village on the Bodensee. With his brother Adolph, he started a construction company that still exists today. But he died before his younger son had turned one year old.[1] My grandmother moved back home to East Bernstadt, in rural eastern Kentucky, where she raised her two sons with the help of her brother Willie.

When John finished high school, the family moved back to Akron, into a three-story brick duplex my grandmother had inherited from her husband. John started taking classes at the University of Akron and working at the Firestone Tire & Rubber factory,[2] but soon enlisted in the Air Force. By 1943, he was flying missions over Western Europe from England, a tailgunner in a B-24 Liberator bomber. Their plane was shot down once, but he survived unharmed. Like many vets, he never talked about his war experiences.

After the war, John used the GI Bill to earn a business degree from Marquette University in Milwaukee. Soon after he returned to Akron, he landed a job as a liquor salesman for the Seagram Company. It was a good match for my outgoing and voluble father. He took an interest in the people he encountered during his workday. The job entailed visiting restaurants and bars in his Ohio territory, schmoozing the owners and bartenders, and persuading them to put his brands in the well. When he was successful, the martini a person ordered was made with Wolfschmidt Vodka or Burnett’s London Dry Gin, the manhattan was made with Carstairs White Seal Whiskey, and his sales numbers rose.

I sensed that he enjoyed those bachelor years. He had a number of cousins in the Akron area who were lifelong friends. When he hung out with them later in his life, I’d sometimes hear them refer to him as Schwing. I never knew the origins of that nickname, and this was decades before the movie Wayne’s World popularized the word, but I always wondered. In any case, he met and married my mother in 1953, and I was born one year later.

John David Duer and Rose Marie Trares, married in 1953.

My father was a notoriously halfass do-it-yourselfer. He never balked at doing any car or house repair project himself. In those days before YouTube tutorials, he might’ve asked for advice from a friend or the guy at the hardware store. More often than not, he just figured it out on his own. The results were less than impressive. When he fixed a toilet, it would flush, but only if we jiggled the handle three times beforehand. He built a shower in our basement laundry room that consisted of a two-foot-high cinder block wall, a flimsy shower curtain, and a wood pallet floor that grew slimy over time. Uncomfortably spartan, it taught us to be adaptable to a wide range of living conditions.

He usually expected my help on these projects, an assignment that mostly consisted of me watching him. He thought I’d learn something from that, but I was just bored. It felt like penance for a sin I didn’t remember committing. I hated watching him stumble through these repair projects, and he often ended up yelling at me and banishing me from the work site, which suited me just fine. And yet, in my adulthood, I became an equally determined and even-more-hapless do-it-yourselfer. But every time I change the oil on my car, I tip my cap to Dad. And my daughter, Emma, who has proven to be twice as handy as either of us, claims I showed her how to confidently take the leap into some of the amazing DIY house projects she’s pulled off.

Starting in fourth grade, I became aware of another side of my dad I could appreciate. A scrappy hard-nosed hoopster, he played pickup basketball well into his mid-forties. I often tagged along for those weekday evening games at the grade school gym.[3] He was five-foot-ten, but never hesitated to mix it up in the paint with bigger and younger players. He had a two-handed set shot that was anachronistic even then, but accurate. I was only five-six in my junior year of high school, but played a lot of neighborhood hoops. When I finally grew up, to six-foot-one, I became a decent baller. During the winter, on Wednesday nights, you could find me at the West Branch Elementary School gym, playing pickup games into my mid-forties, often with guys half my age.

Eventually, my father and I began to broker an uneasy truce. When I was seventeen, after reading Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman and meeting the character Willy Loman, I began to develop a new sympathy for Dad’s life, and for the incredibly short fuse of his fiery temper. However, distance played a role in that truce – I lived with him only twice after high school, once for two months, another time for five. I gave him credit for not badgering me about my vagabonding and my hippie ways during those years. But we still butted heads. When I was on my way to Europe in the summer of 1981, Pat gave me a ride from Iowa City to my family’s home in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Although she and I were not married, it was clear that Pat, Sierra, and I were a family. My father barely disguised his opinion that she was too brash and outspoken, traits that he felt were “unwomanly.” He pulled me aside during that visit and said, “You should not marry that woman.” I was caught off guard, so surprised I didn’t know how to tell him I wasn’t interested in his opinion or advice. When I proposed to Pat six months later, I promised her I’d be a better husband and father than he was. When we were married in a small ceremony in Iowa City, he wasn’t invited.

Over the years, my dad’s low opinion of Pat never seemed to extend to me; however, he struggled to be a good grandfather to our children. He seemed to think it was his job to parent them, instead of unconditionally loving them. But he did eventually recognize the generous heart that Pat kept protected behind her prickly personality. When he was hospitalized in 1997 with stage-four liver cancer, we drove to West Virginia to visit him over a weekend. The kids needed to be back in school, so I drove them home on Sunday, but Pat (who had become a geriatric nurse by then) stayed to nurse him and advocate for his care. She was by his side when he died that Friday.

Twenty-five years later, as my sisters and I cleaned out our mother’s house, we found boxes of promotional novelties left over from Dad’s liquor salesman days, everything from clocks and highball glasses to beach towels and sponges, the kind of stuff once ubiquitous in our home. We divvied up those treasures, those mementos of our youth, that curiously poignant legacy.

Footnotes

[1] I sometimes wonder about the impact this had on my dad. Among other things, it denied him the benefit of having a model for fatherhood.

[2] The four largest U.S. tire companies were then headquartered in Akron, the Rubber Capital of the World.

[3] By watching him, I learned the unsung value of setting a hard screen, making a crisp pass, getting an offensive rebound and kicking it out.

Vagabonding in Europe: The Kids Hike the Vosges

A view of the Château du Frankenbourg ruins, and the Vosges, from a mountain peak just above it.

21.juli.1981 – I was ready to go, the heavy summer air wrestling with my yearning to move, to dance, to ripple in the sun. At the time, I was reading D.H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow, which may have influenced my mood and how I portrayed it in my journal.

Two weeks earlier, I’d met up with my good friend Jim Prchlik in Kassel, Germany. He was staying at a communal flat with his friend Albert Riesselmann. Since then, I’d been hanging out in that city of art and culture, breaking up my stay with hitchhiking excursions to West Berlin and Amsterdam. Jim and I planned to do some hiking and hitchhiking together, but were awaiting the arrival of the third member of our team, Jim’s friend Nancy Faunce from the University of Michigan. When she joined us that evening, our circle was complete. She and Jim had been romantically involved and were still close friends. They’d worked the vendange together the previous fall and then wintered in the Canary Islands off the Moroccan coast before returning to the European continent. At first glance, Nancy appeared delicate, with fair British features, but she was an excellent hiker, strong and energetic. She had a finely calibrated moral compass, attuned to the value of random acts of kindness, sharing her extra pfennigs with anyone who asked, picking up every small bit of trash she came across.

We began to refer to ourselves in the third person – The Kids – characterizing ourselves as playful, light-hearted compagnons de voyage. Our destination was the Vosges, a low mountain range that defines France’s eastern border with Germany. That evening, with our heads full of hash and Peter Tosh's reggae beats, we scurried around, organizing our belongings, loading up our backpacks, preparing for weeks of hiking and camping. We hit the road the next afternoon, grabbing a bus to the autobahn, and as luck would have it, flagging down the first car to pass by, a nice German couple going to Freiberg, who took us within 30 kilometers of Strasbourg, the starting point for our hike in the Vosges.

We met steady rain that day, but as we were being dropped off at a rest area, the setting sun cast a double rainbow across the sky over the Schwarzwald to our west. Our eyes followed the arc of that rainbow as its colors cascaded down to its foot in the valley below us. We set up our camp in the woods and prepared a hearty soup and sandwich supper enjoyed inside the shelter of our orange polyester polygon tent.

In the morning, after hobo coffee and a few slices of good German Roggenbrot,[1] we found ourselves languishing, one exit short of a straight shot to Strasbourg. We traded stories with other hitchhikers, as one often does when the hitching goes slow. So, when a woman dropped off a hitchhiker while we were taking a lunch break, and the others learned she was going to Strasbourg, they told her about us, hailed us away from our lunch, and away we went.

Located on the French side of the Rhine River in the Alsace region,[2] Strasbourg was a lovely city, what we saw of it. We bought baguettes and camping gaz. We searched for a map of Vosges hiking trails but were unwilling to invest 25 French francs in the one we found. Strasbourg’s Cathédrale Notre-Dame was beautiful – delicate reddish brown sandstone spires piercing the sky. Inside, the stone arches and vaulted ceiling harmonized with the bright intricate colors of stained glass. Above the entryway to the church, a rose window proclaimed the Roman Catholic version of a mandala. In one of the side naves a strange contraption – an astronomical clock – displayed seemingly everything,[3] the product of some Renaissance mind. Alas, the mystical peace of the interior seemed to be lost on the herd of tourists tromping through the sacred space.

We left the city, hiking through a couple of adjoining towns until we reached the open road, the foothills of the Vosges in sight to the west and rays of sunlight boosting our spirits. We caught a lift to Barr from a Moroccan drywall installer, and tried to pick up a trail from there. We hiked another four kilometers to Andlau, a town along the Route des Vins d’Alsace, still hunting for a trail, finally camping in a wooded area near a stream west of town, below the medieval ruins of Château d’Andlau. It was raining again, but we were happy to be camping. We quickly set up our tent and fixed a big batch of spaghetti, which we ate with gusto.

Next morning, we sipped strong coffee while packing up, leaving behind the mysteries of stone ruins, rails, cable lifts, never knowing what it was all for. The Kids finally found a trail with a red blaze and decided it was as good as any. We followed those blazes up into the hills, wild raspberries and strawberries along the way, crossing logging roads, past high meadows filled with purple lupine, to a mountain peak (elev. 1,000 m.) from where we could see the Rhine valley to the east and cloud-shrouded valleys and mountains to the west. But we also encountered more rain, cold winds, clouds flying swiftly past us. We pulled out our rain ponchos and hiked onward, getting soaked as we stumbled down the narrow trail, weighed down by our backpacks, our pant legs drenched by wet brush. Jim slipped and took a hard fall, but we all recovered, setting up our tent as more dark clouds settled in.

We closed up the tent, lit a couple candles for warmth, and changed into dry clothes. We soothed ourselves with a multi-course meal of green salad with a yogurt dressing, rice with a hot curry sauce, bread and camembert, the orange that had been serving as our hash pipe, and a taste of milk chocolate. Even with all the cold and rain, it felt good to be there with two friends, laughing at our miseries, sharing our pleasures. It was a moment of grace – a simple life that transformed commonplace comforts into exquisite luxuries – companionship, camaraderie, and the vagabond life, carrying our food and shelter on our backs.

We moved slowly the next morning, letting our gear dry out in the sun. Coffee warmed us while we lingered on the edge of a designated “zone de tranquillité.”[4] We ended up staying that day near the top of Mount Ungersberg (elev. 901 m.). The skies cleared by the afternoon, and the sun wrapped us in its warm arms. I wandered off to pick a mess of raspberries to make a stovetop cake that didn’t turn out as I hoped but was still tasty, savored after the lentil stew and mackerel salad we made and the bottle of wine Nancy had cajoled from a local forestier. I could’ve lived this way indefinitely, but soon Nancy would be leaving us for the fog of London and Jim and I would be continuing south toward the sun of Italy.

The Kids awoke to an early morning rain, but the skies cleared by the time we finished our breakfast of coffee and scrambled eggs, and we were on our way. Down through woods and past vineyards into a valley, we came upon Villé, one in a series of charming Alsatian towns of narrow cobblestone streets and medieval half-timbered homes. We bought camping gaz and foodstuffs and found a good trail map that helped us ascertain our location and route, and then headed for Château du Frankenbourg, located atop a mountain (elev. 750 m.) about 12 kilometers away, a steady uphill hike. As the sun was dipping toward the horizon, we arrived at a 12th-century ruin with a stunning view of surrounding valleys and mountains. We pitched our tent and made a campfire inside the decrepit walls of the château, rewarding ourselves with another of our fine meals – pasta, heavy on the marinara.

Jim and I at our Château du Frankenbourg campsite. Photographs by Nancy.

After a hearty breakfast, we proceeded south out of the hills and then up again towards Haut Koenigsbourg. We stopped for lunch at a convenient picnic table along the trail, the sun pleasantly blazing, and took a bit of a siesta afterward. When we continued our climb, we discovered Haut Koenigsbourg was a hot tourist spot and so made a quick detour. By late afternoon we were back in the woods, heading down the mountain. We came to the town of Thannenkirch and walked about a kilometer beyond to a mountain stream tumbling over rocks. Tired from the heat and the hike, we set up camp there beside the trail. I wandered off to pick the wild cherries – small, sweet, deep red – that abound in the region. They made a delicious fruit salad with yogurt and wild mint, and also spiced up our mushroom and curry rice dish. The night grew chilly as we gazed up at a sky overflowing with a Milky Way of stars.

Wednesday, my 27th birthday, our tent turned bright orange in the morning sun. I received birthday kisses from Jim and Nancy. We sipped our coffee, bathed in the mountain stream – first bath in a week – and lazed in the sun.[5] I stirred up a swarm of bees while picking raspberries, and that woke me up. Off we headed on our trusty red-blaze trail, reaching Château Ribeaupierre an hour later, from whose tower, still standing above ruined walls, we could survey where we’d come from and where we were going. We hiked down into the town of Ribeauvillé, where Jim and Nancy went off to buy groceries and supplies while I reviewed a trail map at the mairie.[6] We decided to head for a refuge a two-hour uphill hike from there.

Sure enough, we found a little hut with a picnic table at Colline du Seerlacken (elev. 633 m.) beside a meadow clearing in the pine forest. While Jim and Nancy gathered firewood, I picked a shirtful of raspberries for dinner. I diced an onion, half a zucchini, and six teeth off a huge head of garlic, stirred that into a flour batter, and pan-fried vegetable fritters over our fire. Nancy made a mushroom sauce, and Jim a hearty salad. Jim pulled from his backpack a bottle of wine they had bought in Ribeauvillé. The next surprise was a box of French waffle crackers and a jar of pâte à tartiner au chocolat noisette.[7] While digesting our dinner and relaxing by the fire, one last marvel was produced – a tall elegant bottle of Gewürtraminer. As this memorable birthday celebration wound down, we sipped the sweet regional favorite, fed the fire, and talked late into the night under a star-speckled sky.

The front cover and inside page of my lovely two-by-three-inch birthday card.

By the time we awoke Thursday morning, Prince Charles and Lady Diana were married. We could sense the excitement even there in rural France. We set off for Kaysersberg, a brisk six-kilometer hike, luckily catching a quick ride from there to Colmar. We went straight to the gare, where Nancy had just enough time to buy her train ticket and join us for one last lunch together. We saw her off with kisses and hugs. Pared down to two, missing Nancy’s spiritedness already, The Kids prepared to push off for the other side of the Rhine. We would continue south toward Italy, traveling together for another month.

Footnotes:

[1] Hobo coffee is made by boiling loose grounds in a pot of water. Roggenbrot is rye bread.

[2] Alsace was the homeland of my maternal grandfather’s line (Trares).

[3] Not only the time of day, but the date, the current zodiac time, and the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets of the Solar System.

[4] According to a sign posted there.

[5] Or as Whitman might say, we leaned and loafed at our ease, observing a spear of summer grass.

[6] City hall.

[7] Chocolate hazelnut spread. Think Nutella.

Vagabonding in Europe: Le Avventure Italiane di Jim e David

Il Colosseo e l'Arco di Costantino a Roma (the setting of a film festival in the summer of 1981)

11 agosto 1981. That Monday morning Jim and I left Venezia – actually we left Camping Mestre, a short bus ride across the Via della Libertà bridge from Venezia. We’d cooked up a breakfast of scrambled eggs and veggies, scavenged a half-dozen packets of dried soup and a pound of rice from a vacated campsite, packed up our tent and gear, and headed for the Autostrada 57 pedaggio.[1]

Jim Prchlik has made numerous appearances in these stories. We both discovered Jack Kerouac’s writing in high school, and were attracted to his Beat vision of The Road as a venue for ecstatic joy and discovery. The summer after we graduated, before Jim started classes at the University of Michigan, we hitchhiked from Ohio to Cape Cod and back. Over the next nine years, our paths frequently intersected – his Ann Arbor home became my travel hub, a place to reenergize, a springboard to new journeys. Like me, Jim had been sandwiching semesters of school in between trips. Completely fluent in three languages, both adventurous and able to go with the flow, he had covered the entire Western Hemisphere, from the Trans Canadian Railway to Argentina.

By the time we met up that summer in Kassel, Germany, at the apartment of his friend Albert “Cruiser” Riesselmann, Jim had been vagabonding around Europe for a year and I’d been there for six weeks. We were now three weeks into our first trip together since that summer after high school. Jim had devised various strategies for extending his stay in Europe – the previous fall he’d worked the vendange[2] in France, this summer he was selling leather pouches he’d made from scraps scored for free. In addition, we reaped the benefits of tourists’ wastefulness and the high aesthetic standards of open-air markets by scavenging lots of fresh food.

That morning, we quickly hitched a ride to Bologna. As we climbed into the back of the step-van, we met another hitchhiker, Sergio, a university student from Roma. We immediately hit it off. When the van driver dropped us off at an area di servizio, Jim and I pulled out our food supplies and shared a lunch with Sergio, who in turn bought us espressos at a nearby bar. When we parted, Sergio gave us his phone number and encouraged us to visit him when we came to Roma. He continued southwest and homeward, and we headed southeast toward the Adriatic coast.

We caught a ride to Rimini from an Italian who spoke excellent English – he was a liaison interpreter between the American military police and Italian carabinieri. On first blush, Rimini was a crowded, boisterous beach resort, an Italian version of some Jersey Shore town. In Italy, everyone takes their vacation in the month of August – all the campgrounds were packed – but it took us a few bus rides and a good bit of walking to learn this. We headed downtown so Jim could try his hand at selling his leatherwork items. Rimini street life was noisy and garish, mostly Italian vacationers, with a sprinkling of French, Germans, and Brits, the kind of outlandish nouveau-riche characters who might appear in the background of a Fellini movie, which was an apt connection because, as I later learned, Fellini was born there.

Jim made no sales that day, but we did meet another street vendor, a young jeweler from Bologna, who offered tips on Italian beach towns farther south more laid-back than Rimini. We found folks camping on the spiaggia libera,[3] so we pitched our tent among them for the night. The beach was free to use but not to camp on, we learned the next morning when the police rousted us, but not before we’d enjoyed a hearty breakfast cooked over our campstove. We spent one more day in Rimini. After a storm blew through that evening, I pitched our tent in a field and waited for Jim to return from his street vending efforts. He came stumbling in, a bit tipsy from a half-bottle of wine he’d found and drank, bummed out by the polyester scene and lack of sales. I cheered him up with a dinner of rice mixed with a can of mushroom ragu found under a bridge while I’d been dodging the storm. We made a good traveling pair – the yang of Jim’s dynamic risk-taking balanced by the yin of my even-keeled care-taking.

Awakened by more rain the next morning, we caught a bus packed with heavy-lidded Italiani to the Rimini train station and then hiked to the autostrada pedaggio. We caught one short ride to the next area di servizio and then a 350-kilometer ride from Rosano, a soft-spoken Veneziano working in München as a fashion model, who was headed to Lecce, near the tip of Italy’s heel. We were tempted to go with him but resisted the impulse, wanting to reach Rome soon, where we hoped mail would be awaiting us. We asked Rosano to drop us off in Lesina, near the Promontorio del Gargano. We hiked ten kilometers out of town, past a couple of campgrounds, along a strand of beach separating the Mare Adriatico from the brackish Lago de Lesinà, on the northeastern edge of the Parco Nazionale del Gargano.[4] Once we found a secluded spot that would serve our need to chill for a few days, we returned to town to buy supplies – bread, wine, candles, matches, cigarettes – and lugged them and four liters of water back to our camp.

Our cigarette of choice at that time, a nonfilter Italian brand.

The next morning, we enjoyed a breakfast of hotcakes and coffee. Afterward, alone for a few minutes, I felt my body and mind go into one of the brief slow-motion fugue states I’d experienced off and on since I was a kid. I could feel each heartbeat, the blood rushing through my body, both helpless and hyperaware as I stepped out of myself and into the delicious intensity of each passing second.

We were writing, swimming, letting the sun tan our bodies a shade darker and bleach our hair a shade lighter. Reading the first volume of Anaïs Nin’s diaries, I was inspired by her writing to be precise and honest in my own journals. Gathering driftwood on the beach for our fires, I found ouzo bottles imprinted with Greek letters, a good black ink pen, the plastic leg of a babydoll that we mounted atop our tentpole, a kind of amulet. Sitting around our campfire, we watched a storm far out at sea, lightning reflecting off the water, a full moon hanging overhead. A bottle of wine, cigarettes, and good brotherly talk.

We camped four nights on that beach, staying until we had depleted our food supplies. Sunday morning, more good luck hitching the autostrada – north along the coast to Pescara, then west into the Abruzzo region and the dry western slopes of the Apennines. We stopped for lunch in sleepy little Pescina, the midday sun intense but the air comfortably arid as we rested on a stone wall beneath the shade of the piazza’s only tree. We got a ride to the last area di servizio before Rome, where we hoped to call Sergio, but all the phones were out of order, so we camped in an adjacent field.

Early Monday we hustled up a ride to the outskirts of the city, caught a bus al centro and walked to an American Express office near the Piazza di Spagna, where a letter from Pat and three others were awaiting me. We drank espressos at an outdoor cafe, read our mail, felt the rush of connecting with lives back home, and promptly wrote responses. Rome was the first address I’d given Pat to reach me, and her letter was an eight-page outpouring of her and Sierra’s feelings for me: “I find myself becoming selfish sometimes, wanting you to come home. But I want this trip to be special for you. And I want you to want to come home to me when it’s done.”

By two that afternoon, we were ringing Sergio, who responded warmly and gave us directions to his apartment in the Monte Sacro quarter. We arrived in time for the final course of a long leisurely lunch – dolce i caffè. Sergio welcomed us, introducing us to a group of friends snugly gathered around a long table in his kitchen – Gianni, Roberta, Grazia, Gino, Jordi, Valeria, Natalia, Ana, Marco. We filled our stomachs and heads with good things. That evening, refreshed by our first hot shower in weeks, we joined the group to catch a movie at the Maxentius Film Festival, some American western dubbed in Serbian with Arabic subtitles, projected simultaneously onto four screens in the open space between Il Colosseo and the Arco di Costantino. A wondrously jarring experience – watching a movie and then turning to notice the walls of a structure that has withstood two thousand years of history.[5]

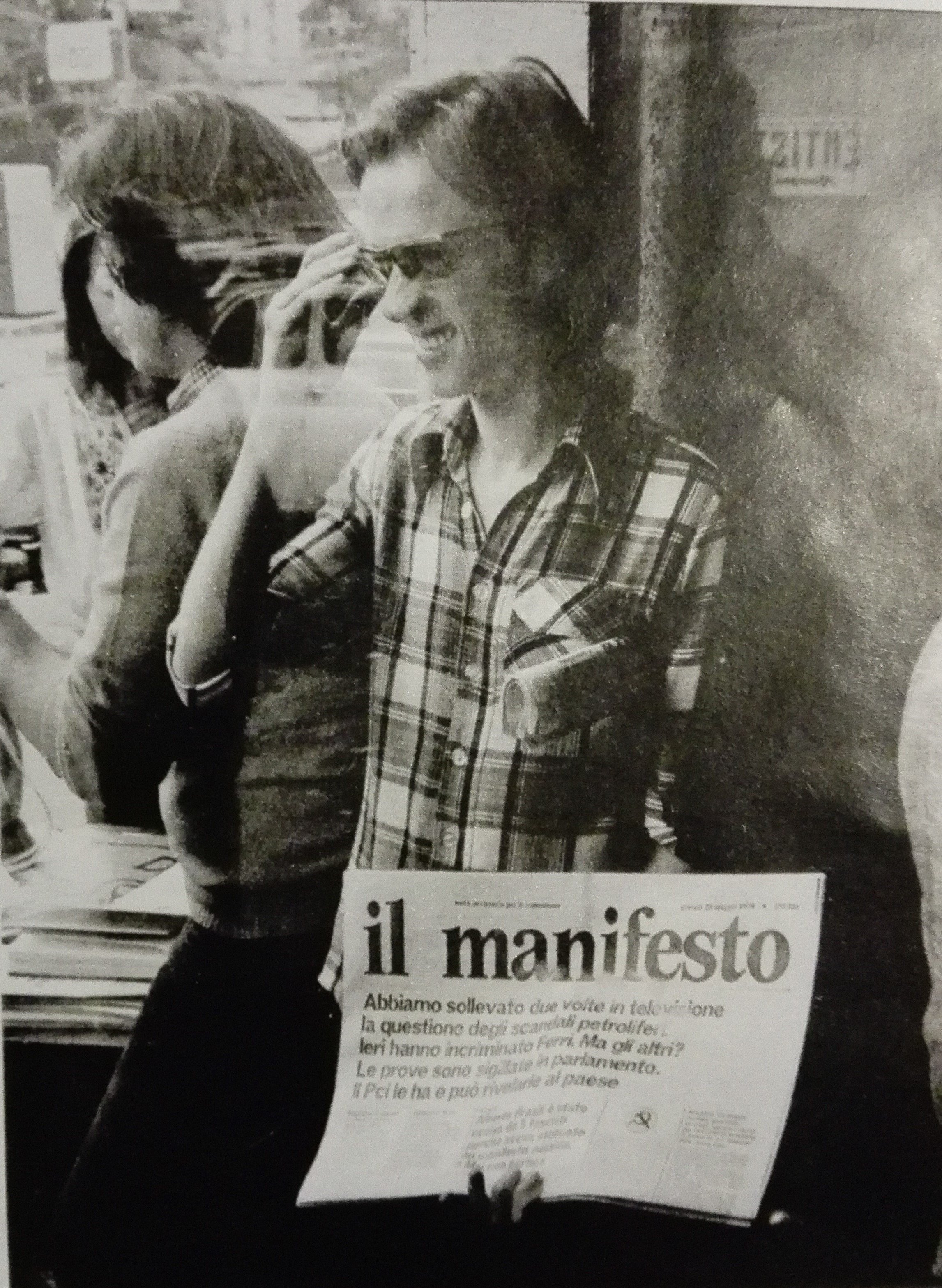

Left, Sergio’s friends sitting under La Madonnina in Piazza Sempione, the central square of Mante Sacro (photo taken in the late ‘70s). Right, Sergio hawking the left-wing Rome daily Il Manifesto (photo taken in 1974-75).

We stayed a week with Sergio, who had opened his house to not only us but also Roberta, Jordi, and Gianni during their August break from studies. I grew to appreciate the style of our amici italian – their generosity and natural intimacy, the abundance of kisses and embraces shared every time we met or parted. One evening, a group of us gathered in a quiet bar on the Isola Tiberina, in the middle of il Fiume Tevere in the middle of the city. For hours, we drank beer and discoursed on art and politics, conducting the melodious words with our hands.[6] As Gianni said, “How else to act with that much history resting on your shoulders.” Our group relocated to Massenzio, where films played all night, free after midnight. A spina was fired up and passed around, and we danced loose and crazy to a Bob Marley concert movie. By 3 a.m. Sergio was driving us homeward through the empty streets, the spotlit buildings, monuments, and ruins whizzing past like a dream.

Tuesday afternoon, Roberta took me shopping for a new pair of shoes. I was looking for a pair of espadrilles like the ones worn by many young Italians. They looked so comfortable, just canvas and jute with rubber soles, but I struggled to find a pair that fit my size 45 feet, so I settled on a simple pair of sandals. The best part of the shopping trip, though, was Sergio letting us use his Fiat and Roberta letting me drive it through the streets of Roma. Ah, the thrill of merging into the roundabout encircling the gorgeous fountain-filled Piazza della Repubblica.

On Wednesday, we made dinner for our friends. Gianni took us shopping for supplies. I delighted in the many stops we made at shops and stalls in the open-air market, la lingua del mercato, red and green peppers bursting with dolcezza, aromatic garlands di aglio, black olives swimming in barrels of olio d’oliva, pomodori San Marzano, grown on the volcanic soil of Vesuvius.[7] I made a frijoles con queso casserole with cornbread crust.[8] While Jim and I were out earlier that day, he discovered a sizable chunk of hash in a Piazza Navona trash can – perhaps intercepting a drop or salvaging what some nervous lad fearful of being busted had jettisoned. In any case, he donated it to the communal stash.

Thursday afternoon, Grazia and her sister Analisa took Jim and me to the countryside northeast of Roma. Grazia and Jim had made a good connection and spent the previous night together. She was fun and likable – a vivacious bundle of energy and fiercely held opinions. We went for a swim in Lago di Bracciano, and then lazed in the last hour of sunshine. In nearby Trevignano, we met up with Gianni, Jordi, and Roberta, drank beers, went off to smoke a spina, and reconvened at a trattoria where we were served massive plates of pasta at a long outdoor table. Later, we drove to a villa owned by Roberta’s family, a rustic farmhouse set against a terraced hillside and surrounded by a courtyard garden. Under the stars we shared another joint of hash and talked feminist and Marxist politics until I wandered off to a bed of straw in a grape arbor, the fruit hanging overhead like the eggs of Bacchus. My thoughts turned to Pat and Sierra. How I missed the rich entanglements of our home life. But oh, how I cherished the constant novelty of this vagabond life.