Finding My Place #2: Communal Life

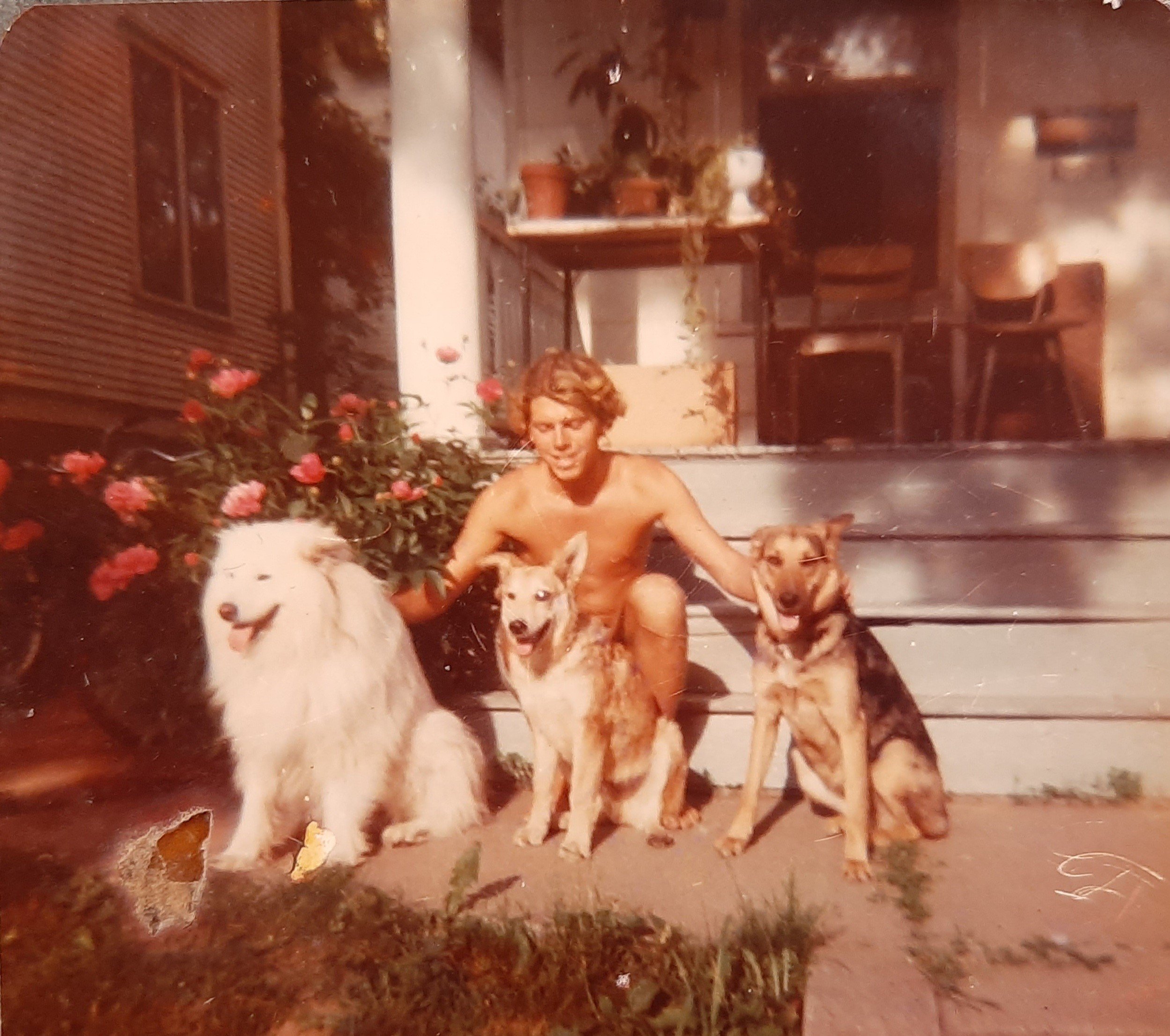

The dogs of Governor Steet House - Sam the Samoyed, Shalom, GD Walker, and me.

In June 1976, I became part of a communal household. My friend Pat had recently moved into a big house at 308 South Governor Street. The other four house members (three of whom were named David) had completed their academic studies and were leaving town or getting ready to do so. I replaced one of those Davids. Despite that, we never called it the House of David; it was always the Governor Street House.

I was following a path blazed by many others in the late sixties and early seventies.[1] We were joining rural and urban communes to build a culture that challenged the superficial and materialistic one of our parents. The house became a learning lab where we explored alternatives to that mainstream culture, and its mindless pursuit of money and status, its increasing isolation into detached nuclear families, its overreliance on technology that denied us the joy of working with our hands, its misguided belief that nature existed merely to serve our needs.

The house itself had been built in the American Foursquare style, with a full-length front porch, a front bay window with patterned glass, a hipped roof with three hipped dormer windows, and Craftsman-style oak woodwork inside. It was laid out in the typically efficient Foursquare style: From front to back on the first floor: foyer, stairway, and kitchen on the left side, living room and dining room on the right side. On the second floor, a bedroom in each corner and a centrally located bathroom and stairway. The attic was unfinished, a single large room with plywood flooring and the dormer windows admitting light.

My first meal in the house was memorable. I’d spent the afternoon getting familiar with the general layout and rules of the house. Pat and one of the Davids made a huge salad, using produce from the garden that filled our small backyard, and another David had baked bread that morning. As the sun was setting and the night insects commenced their chorus, we sat around a small wooden table just outside the kitchen’s back door, on a porch sheltered by a roof and an east-facing trellis thick with vines. I was charmed by it all – the beautiful spring evening, the hearty salad, the fresh-baked bread, the company of like-minded folks who offered the promise of a family.

Over the course of the summer, we recruited two housemates – Bob and Mary – friends we knew through New Pioneer Co-op. We were committed to living communally: sharing the costs of rent and utilities, and the duties of shopping, cooking, cleaning, and gardening. We baked our own bread and made our own yogurt. The refrigerator always contained a gallon jar of alfalfa or mung bean sprouts that we’d grown from seed. We were learning the practices of sustainable living: “If it’s brown, flush it down; if it’s yellow, let it mellow.” Although we had different work or class schedules, we ate together as much as possible and held weekly house meetings where we coordinated the work of housekeeping and addressed the tensions that arose from living together. We’d remind each other to put peanut butter on the shopping list when the jar got emptied and turn down the stereo after eleven o’clock.

Although we saw this as an idealistic exercise in creating a community based on collectivist principles, living together also offered more pragmatic benefits. Depending on how many people lived in the house, each person’s rent obligation was between 50 and 75 dollars. Sharing household duties gave us more free time and sharing expenses allowed us to hold jobs that perhaps offered no more than subsistence wages but were fulfilling and compatible with our politics.

Living in town, however, wasn’t always compatible with our politics. Across the street stood the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority. During fall rush, we’d sit on our front porch, loudly deriding the silly recruitment skits and cheers they performed on their lawn. A sorority is definitely not a commune. We also had regular run-ins with our elderly next-door neighbor, Mr. Deming, who’d call animal control because we let our dogs hang out on the front porch unleashed, and the police because we let our babies hang out on the front porch unclothed.

For the next two years, the Governor Street House served as my home base. After returning in April 1977 from six months in Mexico, I moved into the attic. In the summer I sprawled out in the middle of that space, but in the winter, I hunkered down by the south dormer window, in a corner closed off with heavy plastic sheeting and kept above freezing by a space heater. Many people whom I still count as friends were part of the Governor Street House’s revolving door of housemates ‒ Pat, Mary, Bob, Steve, Sharon, Mara, Michael, John, Paul, Patricia, Maggie, Willow, Jim, among others.[2] The ceramicist Jean Graham moved her pottery studio into our basement and pitched in twenty bucks each month to help with rent. When we realized we had to pay a fee whenever we changed the utilities to someone else’s name, we had all the bills permanently put in the name of GD Walker, Pat’s Australian cattle dog.

On a cold night in February 1978, the Governor Street House became multi-generational when Pat gave birth to her son Sierra in her northwest corner bedroom. Four people gathered in that room to assist Pat with her labor – Mary, our housemate; Zap, the father; and Sharon and Amy, trained midwives associated with the Emma Goldman Clinic. Bob and I waited downstairs, hovering on the edge of that excitement.

Pat at Governor Street House one week before giving birth to Sierra.

The previous year, Ina May Gaskin’s book Spiritual Midwifery had been published, encouraging women to regain control of the birthing process and instructing them on the practices of natural childbirth. The book advocated for the end to unnecessary hospital births for the convenience of male doctors – the end to unnecessary general anesthesia, forceps deliveries, and episiotomies. In 1971, Gaskin[3] and her husband Stephen had led a bus caravan from San Francisco, eventually settling in rural Tennessee and starting a commune called The Farm. She established one of the first out-of-hospital birthing centers in the United States. Women traveled there not only to give birth to their children but to learn the skills of midwifery.

Pat’s contractions had started on Wednesday, slowly building in intensity over the next four days, although without causing any cervical dilation. On Friday, to distract herself, she went to a movie and did some shopping. The midwives arrived at 9:30 on Saturday night, and Sierra was born six hours later. I was deeply moved by the experience, which I tried to express in this poem.

We Surround Ourselves with Mysteries

in every window

a lit candle stands

burning the vapors of our vigil

atmosphere soaked in stillness

barely swirls

in a leaden cloud of expectation

the midwives arrive

and their female strength is felt

sure hands and sure hearts

outside a fog distance and

the lights of a parked car

its engine running

holding the bone of drama

we watch from outside the circle

sterilize instruments bring hot compresses

inside woman is a fierce muscle

pain lays its hand on her forehead

warm blood the color of life

the door to the universe slowly opens

enough for us to glimpse its magic

as the babe slips out a first cry

sunday morning two hours till dawn

he sleeps a new life

the center of a ring of adoration

today i swear an allegiance

to be aware of every moment every detail

filling the vessel of my body

The household had a new shared responsibility, and we all did our best to support Pat and help with childcare. We cherished Sierra, even though he was colicky those first few months. He wouldn’t be the only child raised in the house ‒ Patricia and Paul’s Dylan and Willow’s Sienna later lived there.

Governor Street House wasn’t the only communal house in Iowa City at that time. Two houses directly across from each other on the 400 block of South Johnson Street, one on the corner of South Dubuque and East Court streets, one on the corner of North Dubuque and Davenport streets, one at the end of East Washington Street, one at 811 East Market Street, and a house on McLean Street on the west side of the river.[4] A couple of communal farmsteads had also been established within twenty miles of Iowa City. Most of the house members were part of the tight-knit New Pioneer Co-op community, and many worked at either New Pioneer, Blooming Prairie Warehouse, Stone Soup Restaurant, or Morning Glory Bakery.

In 2009, inspired by memories of communal households they’d lived in during their youth, a group of people began meeting to plan an alternative to traditional housing in Iowa City, based on the Danish cohousing model. They envisioned a socially and economically diverse multi-generational community that makes decisions using the consensus model, and shares jointly owned common space and resources while inhabiting separate living quarters with small carbon footprints. The last of the 37 units of Iowa City Cohousing, settled on 7.3-acre Prairie Hill, just off West Benton Street, are now being completed.

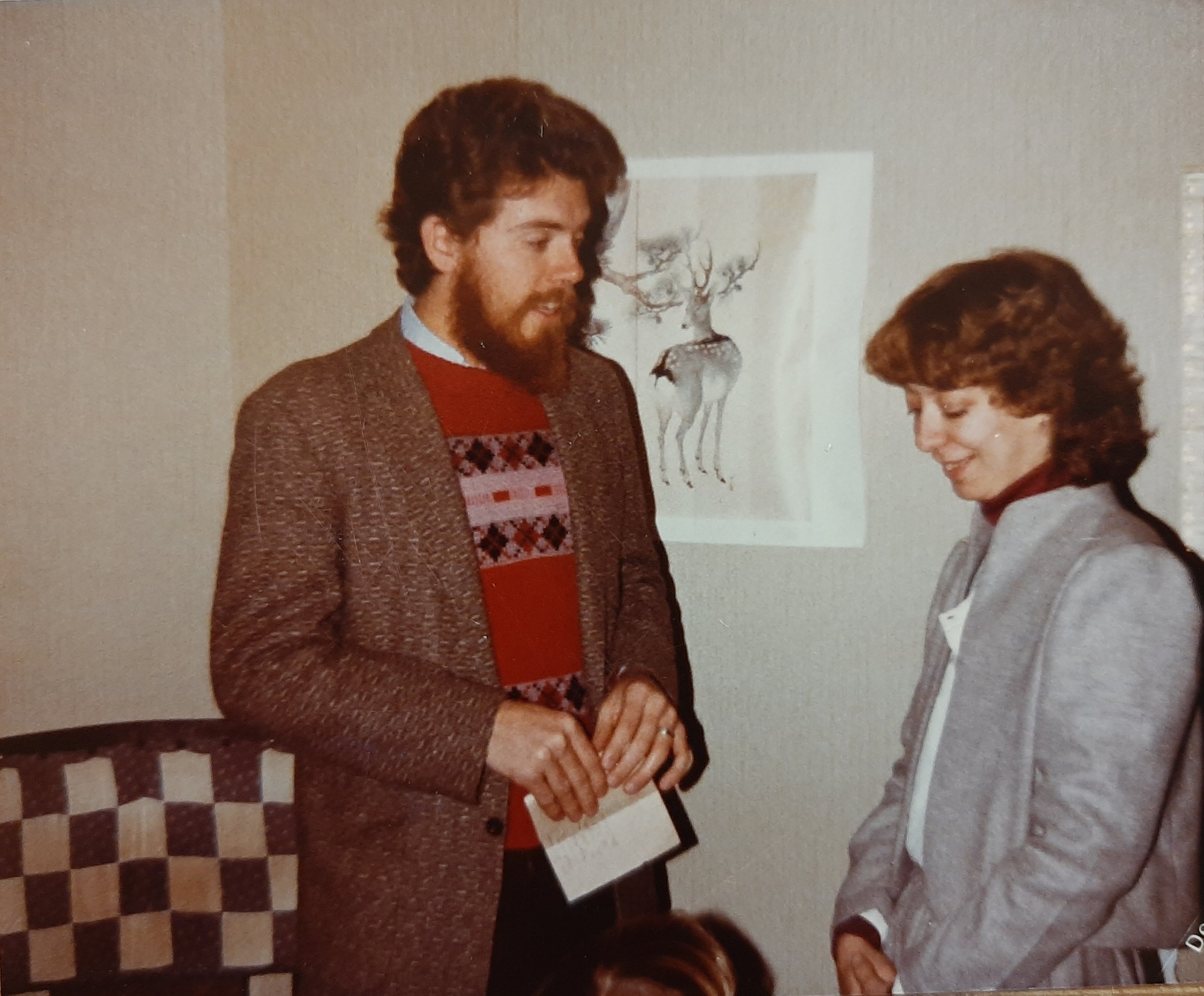

In August 1978, over two years after first moving in, I left the Governor Street House just as Pat and Sierra were also relocating to their own apartment on the southeast edge of town.[5] But in May 1980, after a four-month trip to Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, I rejoined Pat, Sierra, Steve, and Mary in the Market Street House. After finally finishing my undergraduate studies, and then spending another four months traveling around Europe, I returned to Market Street and moved into the attic. Sierra’s bedroom was at the bottom of the attic stairs, and I’d often come down at night to get him up to pee. Two months after I returned, I asked Pat if she’d marry me. And on December 6, 1981, Pat, Sierra, and I bound our lives together at the Market Street House, exchanging vows among a close group of friends, many of whom we’d lived with at one time or another.

Footnotes:

[1] It’s been estimated that in the U.S. as many as 3,000 communes were founded during this time, inhabited primarily by disaffected white, middle-class kids.

[2] The camaraderie and physical intimacy of commune life sometimes led to spontaneous liaisons. So much so that, years later, when six or seven of us were reflecting about those days after a meal together, we suddenly realized that, at one point or another, most of us had slept with nearly everyone else at that table.

[3] Ina May Gaskin grew up in Marshalltown, Iowa, and in the early sixties, earned a bachelor’s degree in English literature from the University of Iowa.

[4] Formed in 1977, River City Housing Collective carries on this tradition. Three houses offer a cooperative alternative to the tenant-landlord relationship – Bloom County House at 935 E. College St., Summit House at 200 S. Summit St., and Anomy House at 802 E. Washington St.

[5] Meanwhile, Zap was getting ready to move to Santa Cruz to pursue a musical career, and began to play an increasingly smaller role in raising Sierra.