Ways to Endure, Part 3

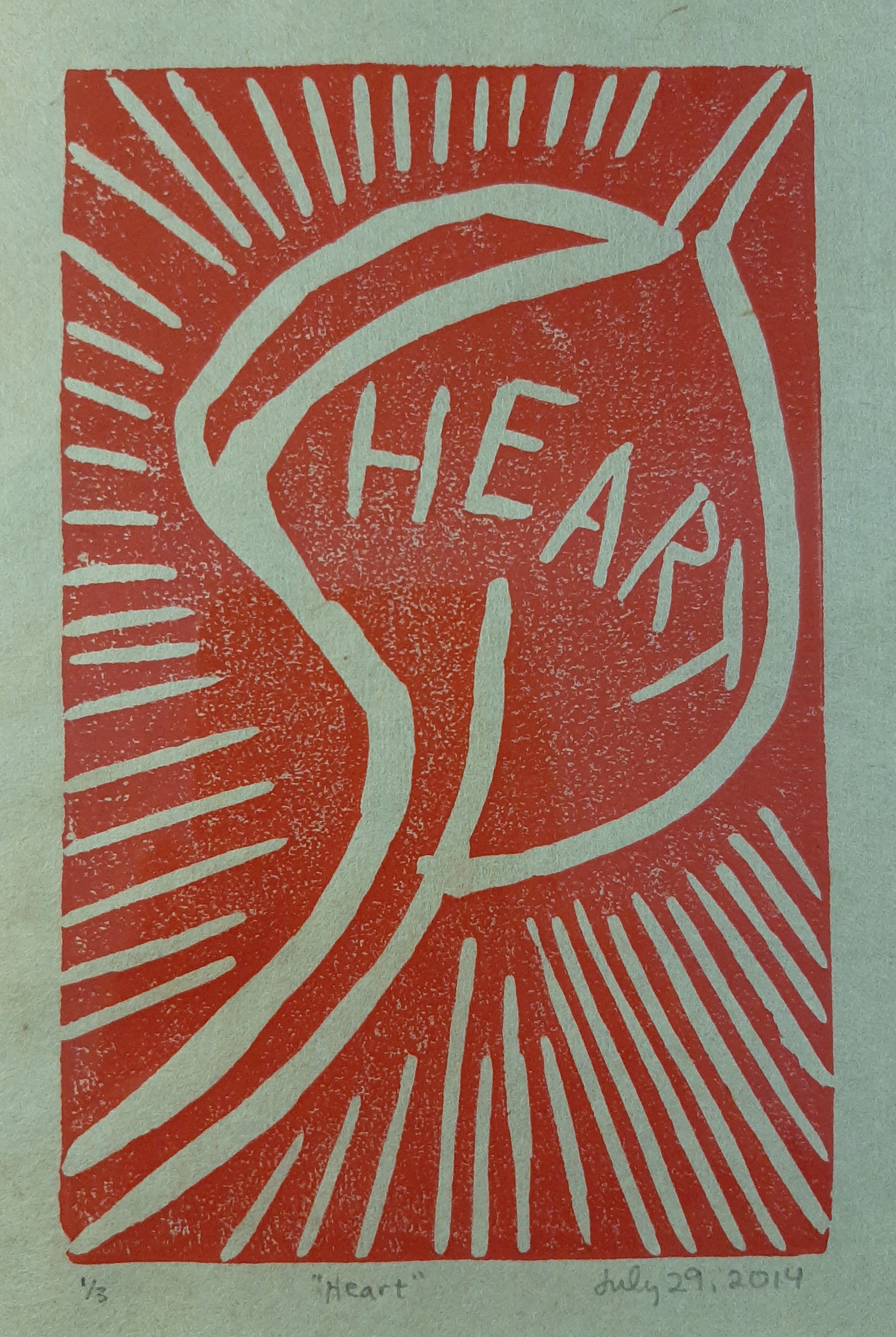

Helping with an Iowa Youth Writing Project workshop on Art & Writing, I made this linoleum block print at the Iowa City Press Coop with Pat in mind.

My daughter, Emma, recently mentioned that the golden anniversary of her mother and my wife’s death was approaching – five years ago on November 5 she died. I’ll always be able to count on Emma to remind me to hold Pat in the light.[1] I’ve been looking through Pat’s recipe box, recalling favorite dishes, and promising to make some, although her recipes usually lack instructions and often lack quantities – they’re more like reminders. For Thanksgiving this year, I made the oatmeal rolls we traditionally devoured with that meal. I thought of Pat as I savored the nutty flavor of those soft, dense rolls on her favorite holiday of the year.

After Pat’s second open-heart surgery in September 2009, our lives regained a small measure of stability. But as her health and strength improved, she began to confront the loss of focus that materialized at the end of her career as a geriatric nurse and nursing director. She scheduled a weekly appointment with a psychologist, and although I imagined I could have helped her deal with her anger and frustration, I came to realize what a smart move that was. She needed someone with professional training and with no emotional investment who could help her gain perspective and point her toward emotional stability.

I never attempted to pry into those conversations between Pat and her therapist. But if she shared an insightful comment after a session, I’d file it away. When Pat would go into an anxiety spiral about her health, I could sometimes calm her with “Remember what Amy said …” It helped that I could couch that advice as coming from her therapist, not me.

One suggestion the therapist made was to get involved in a volunteer program. Pat began to help with Meals on Wheels, picking up twenty-five hot lunches from The Senior Center every day and delivering them to homebound clients on Iowa City’s east side. The work revived that sense of purpose she sorely missed. It became a way for her to continue to care for the elderly and disabled.[2]

In 2010, we began to appreciate the joy of watching our children growing into adulthood. Sierra was finishing up a master’s degree in Japanese history at Columbia University and working as an assistant producer for a news correspondent at Tokyo Broadcasting System Television. Jesse was holding down a good sous-chef job at Leaf Kitchen and had moved in with his girlfriend, Emily. Although he was still struggling with alcoholism, we were hoping a steady job and girlfriend might help him right his ship. And in early 2011, Emma announced she was getting married. Her fiance, Zach, was an intermedia artist from northern Minnesota wrapping up an MFA at the university, a tall, easy-going guy.

Emma wanted a big wedding that would bring together all our friends and family, but she also wanted it to express her personal style and tastes. This would be a casual DIY affair, the vibe equal parts artist, neo-hippie, and Quaker, and no wedding planner was going to tell her otherwise. It was a delight to see Emma and Pat work together to plan the event.

It was about this time that Pat began to realize all was not well with her heart. Loeys-Dietz Syndrome – the connective tissue disorder that caused the aneurysms and dissections wreaking havoc on her cardiothoracic system – was at it again. Pat often felt tired and lightheaded, the effects of low blood pressure. Her cardiac surgeon, Dr. Farivar, described it as “increasing symptoms of severe aortic deficiency.” Based on the echocardiograms, he concluded that the primary culprit was a faulty aortic valve, and recommended Pat undergo a minimally invasive surgery to have it replaced. Without missing a beat, Pat agreed to the surgery. The memory of the first surgery, which she barely survived, would’ve caused me to pause. But for Pat, it was “Fix this right away – I need to be there for my daughter on her wedding day.”

The surgery was scheduled for June 2, the day after my last day of classes. I took a stack of essay finals with me to the Day of Surgery waiting room, hoping that grading them would occupy and distract me during the long surgery. Dr. Farivar planned to replace the damaged aortic valve with a porcine valve. The use of pig heart valves dates back to 1965. Similar in size, weight, and structure to human hearts, the hearts of pigs grown for human consumption are often used for medical purposes. The next time Pat and I had bacon for breakfast, we joked it might be the same pig donating his heart valve to her.

Pat took the lead-up to this surgery more in stride than I did. Dr. Farivar had called it “minimally invasive,” but it was still open heart surgery. At some point, I tried to write my way through my fears so I could set them aside and stand by her side. It was my way of whistling in the dark.

The ascending aorta

The descending aorta

The septum and the right atrium

The vena cava and the aortic arch

The wondrous architecture of the heart

An architecture with structural damage

A weakening of the arterial walls

An anomalous bulge on the MRI scans

The dreadful lyricism of “aortic aneurysm”

Yet my wife’s heart is strong, stubborn, resilient

I’ve danced to its fierce beat

For thirty years

And her cardiac surgeon

Can replace a ransacked chamber

Of her heart with that of “some pig”

Can remove a vein from her thigh

Switch it with a ticking aneurysm

And stitch it securely into place

With the delicate precision of knots

Handed down by generations

Of Persian carpet weavers

So that my wife’s heart

Can go on beating

Pumping

Loving

The full surgical procedure took nine hours. Pat’s body was on a cardiopulmonary bypass pump for 134 minutes. But nearly everything went as planned. Reviewing Dr. Farivar’s post-op procedure notes recently, I was struck by the unusual beauty of his medical language: “Using a pediatric ball tip sucker, we emptied the heart out. We placed a pediatric wire-reinforced sump to drain the heart. The valve was insufficient and floppy…. We then placed twelve pledgeted mattress sutures in a non-everting manner in the aortic annulus…. We closed the aorta with a teardrop-shaped bovine pericardial patch in order to minimize any fish-mouthing of the coronary artery…. We de-aired the heart with provocative maneuvers.”

One hiccup in the surgery occurred when the medical team cracked Pat’s chest. Her breastbone (sternum) had not healed from the first two surgeries. When they removed the wires holding together the two halves of her sternum, the bone fractured on both sides. When it came time to close up Pat’s chest, they decided to use two titanium plates shaped to fit on either side of the aorta, held in place by four self-tapping screws and double wires. According to Farivar’s post-op notes, “The patient tolerated the procedure well.” Well, I guess.

From then on, those breastplates would cause annoying red-tape delays at airport security. Although the titanium might suggest Pat was working on her Iron Woman armor, it made me more sensitive to her fragility. If I slowly ran my fingers over her sternum, I could feel the screws.

Pat recovered more quickly than she did from the previous surgeries. She was extubated the day after the surgery, moved to the general ward the day after that, and discharged three days after that. Because of the extraordinary sternal repairs, discharge instructions included no driving for four weeks and no lifting, pushing, or pulling more than five pounds for eight weeks. Emma and Zach’s wedding date was eight weeks away.

During the two weeks leading up to the marriage, all our efforts were focused on making the event as beautiful as possible within our means, and Pat worked harder than anyone. We hired a photographer. Jesse played a major role in preparing the dinner catered by Leaf Kitchen for our 250 guests. Everything else was done by us and our friends. Our musician friend John played songs as guests arrived for the ceremony. Each table was adorned with a vaseful of flowers from our friend Mary’s gardens. In lieu of a band, Sierra compiled a great playlist and became our deejay for the day. Instead of providing a traditional wedding cake, we asked guests to bring homemade pies. At least thirty-five pies of every possible type showed up.

At the wedding reception, from left to right, Jesse, Emma, Zach (in the background), and Sierra.

The wedding took place on a steamy mid-August day thirty miles west of Iowa City in Amana, one of the seven villages of the Amana Colonies.[3] Emma and Zach were married in a grassy field overlooking farmland near the Festhalle Barn, a restored century-old dairy barn that served as the wedding reception venue. The ceremony began with Pat escorting her daughter down the aisle toward Zach and me, all of us beaming and teary-eyed. Emma had filled out an on-line application so I could be ordained in the Universal Life Church and officiate the ceremony.

The reception brought together in one building forty members of my immediate family without, as far as I could tell, any of the squabbling typical of most families that size. Then again, I was in a place that left no room for any pettiness that might interfere with my joy. Everyone looked exceptionally beautiful. The little white lights strung up in the rafters glowed like stars. Like everyone else there, I was honoring the love shared by those two young people, but I was also honoring the unstoppable will of my wife. She was not about to let the “single nucleotide mutation at position 605 in axon 4”[4] keep her from celebrating the wedding of her daughter with family and friends.

Footnotes:

[1] A common (and personal favorite) way of referring to prayer among Quaker Friends.

[2] On one Meals on Wheels run, Pat had the misfortune to have her car stolen. She’d left it running in the alley beside the Senior Center while she slipped inside to grab the insulated meal carrier bags. When she came out a minute later, the car was gone. We filed a stolen vehicle report with the police, hoping the car would turn up. And it did a week later – in Anamosa, thirty-five miles away. A neighbor of the man who stole the car, suspecting he’d come by that late-model minivan parked in front of his house by illegal means, turned him in to the police.

[3] The Amana Colonies were settled in 1856 by German Radical Pietists escaping religious persecution. Their members lived communally and self-sufficiently until 1932, and that history survives in the many shops that sell the products of local woolen mills, furniture shops, clockmakers, smokehouses, breweries, wineries, bakeries.

[4] The genetic diagnosis of Loeys-Dietz Syndrome.